With 40 traffic fatalities, the District had its deadliest year on the roads since 2007. The upward trend included two kids who hadn’t even started 1st grade yet, one elementary school student paralyzed, and two others seriously injured.

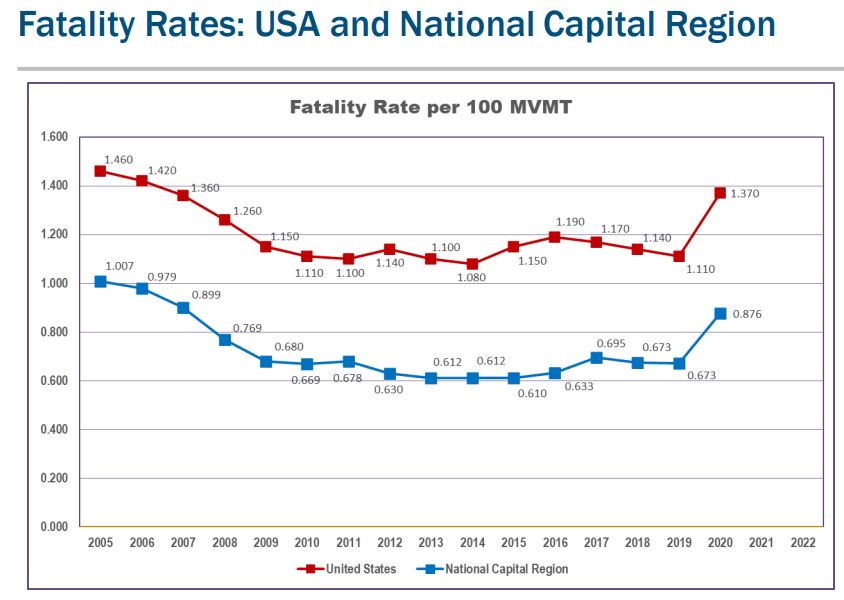

Across the region, preliminary numbers show that at least 282 people were killed on the roads, a 6% increase from an already bad 2020 and a 12% increase from 2019. Numbers are usually finalized a few months into the new year. Nationally, the first half of 2021 saw an 18% increase in traffic deaths compared to 2020, the largest increase on record. Experts have attributed the rise to fewer drivers on the road and increased speeds, more anti-social driving behavior, distracted driving, and decreased seat belt use. The pandemic has also brought on more alcohol and drug use and rising homicides.

Half of the people killed in D.C. were not in a vehicle, with 17 pedestrians being hit and killed and three on bikes. Nine motorcyclists, nine drivers, and two passengers also were killed. Half of the deaths in D.C. came in Wards 7 and 8. The problem in D.C. has gotten so bad, that advocates are calling for a complete reset of the Vision Zero program Mayor Muriel Bowser committed to in 2015.

The Vision Zero goal is to eliminate traffic deaths by 2024, which will not be met unless a miraculous change happens in the next two years.

Traffic deaths have increased every year, except one, since the District launched the program. D.C.’s independent auditor is also investigating the program.

Among the 40 lives lost this year, 4-year-old Zyaire Joshua, 5-year-old Allison Hart, 24-year-old opera singer Nina Larson, cyclist Jim Pagels, advocates for ending homelessness Waldon Adams and Rhonda Whitaker, and Armando Martinez-Ramos, who was delivering food on a bike. Councilmember Janeese Lewis George said the deaths of the two children jumpstarted the conversation around traffic safety.

“That has moved the needle… and I think a breaking point has been reached in our communities and amongst our (council) colleagues,” Lewis George said in December. “Our communities are speaking loudly… and have done their part to advocate for safety… it’s time for the government to finally do its part by making it safe for our children to get to school.”

The District Department of Transportation, D.C. Council, Mayor’s office, and other departments are trying several things to curb the increase.

In April, a police reform commission recommended moving traffic enforcement from MPD to DDOT, but it’s unclear if or when that will happen. The recommendation was part of a larger study looking to reform police work in light of the recent social justice movement. Those in favor of the idea said it would take the use-of-force out of traffic stops, put more focus on traffic safety, and free up police for other public safety work.

In May, Bowser pledged $10 million for more speed cameras and to improve dangerous intersections.

In October, DDOT pledged to increase the speed of “Traffic Safety Investigations” requested by residents. Many residents and Advisory Neighborhood Commissioners use this process to try to make their neighborhood streets safer, but there are many steps involved and often takes years for results. The DDOT pledged to tackle 50 safety improvement projects including adding speed bumps and new stop signs, and other traffic calming devices.

In November, Bowser pledged seven police officers to rotate to different school zones to do more enforcement in school zones.

In December, after Hart’s death, advocates, neighbors, and family members gathered for a “chalk in” vigil to give people a space to heal and process the loss.

Multiple crashes on Wheeler Road involving kids forced changes including a new speed camera and a project to narrow the dangerous road.

Bowser’s administration also approved reduced car space and more bike lanes on 9th Street in Shaw and on Connecticut Avenue. These two projects, which are key new corridors for cycling, have been discussed for years and finally got the go-ahead.

The Data

- In Maryland, some counties, like Montgomery County, have their own open data portals that list fatalities.

- The Virginia Department of Motor Vehicles maintains an interactive crash database for users to drill down into specific details for both counties and cities.

- The District Department of Transportation and the Metropolitan Police Department hold data for D.C.

At the end of the year, councilmembers introduced a flurry of bills to make school zones safer and mandate raised crosswalks and other infrastructure that aims to slow drivers and protect pedestrians.

But there were also failures in 2021. In 2020, the D.C. Council demanded Bowser negotiate ticket reciprocity with Virginia and Maryland by Oct. 2021 to hold their drivers accountable for speed and red light camera tickets. Drivers from those states, who make up a large portion of camera tickets, aren’t forced to pay those tickets or have their registration and licenses put on hold since those tickets aren’t issued by a law enforcement officer. The administration never tried to get that done. Now the regional Transportation Planning Board has reached out to all parties urging the change.

Elsewhere in the region, Prince William County in Virginia and Prince George’s County in Maryland had the highest number of deaths in recent years, too. Prince George's County aims to eliminate traffic deaths by 2040 and has identified a network of high-risk stretches for pedestrians and cyclists, almost all of them are within the Beltway.

Like D.C., two kids were killed in traffic in the county last year. Prince William County Police told Fox 5 that they attribute the increase to higher driving speeds.

"Speed reduces that amount of time that you have to properly react and properly stop the vehicle and take those evasive maneuvers to avoid a collision," Sgt. Jonathan Perok, Public Information Officer for Prince William County police said. "Speeding has always been a problem and unfortunately that’s going to take a conscious effort on the part of drivers."

Jordan Pascale

Jordan Pascale