Reverend Volodymyr Steliac hasn’t gotten much sleep in the past few days. A leader in the local Ukrainian community, he’s kept his church doors open day and night for his parishioners to come and pray. With what little time he gets to himself, he stays awake reading.

As news of a Russian invasion – and Ukrainian resistance – continues to unfold, the church’s walls have become a place of solace for him and his community.

“We Ukrainian people are being killed every minute as we speak,” said Steliac during Sunday’s services at St. Andrew Ukrainian Orthodox Church. “Please pray like you’ve never prayed before.”

With roots dating back to the arrival of Ukrainian immigrants to the D.C. area after World War II, the Silver Spring church has long served as a community anchor throughout the region. It’s a place where people can worship, celebrate weddings, and hold funeral processions. There’s even an annual festival in September to celebrate with music, dancers and food like Ukrainian kielbasa and Kozak beer. But in the last few days, the church’s services have extended far beyond that.

“I’ve never seen [this kind of] outpouring of love and support,” continued Steliac, who has served his parish since 2001. “Flowers in front of the church, people walking in, neighbors leaving cash donations.”

Olga Baczara lives in Annapolis but drives every weekend to attend services. And during a time of fear and anxiety, she’s found an even greater sense of community.

“This is the center of Ukrainian American community,” said Baczara, who immigrated to the U.S in 1993. “We have yearly festivals when there’s a happy time… But when we have an enemy to fight, somebody who takes away our independence, we also unite.”

When Baczara got word last week that Russia had started bombing Ukrainian cities, she thought of her family still living there. She knew she had to help her younger sister, Ivanna Ivaniv, and her three children get out safely.

After waking her children in the middle of the night, Ivaniv packed toothbrushes and two changes of clothes before setting off, she later told Baczara. The sisters stayed in constant communication over a messenger app as Ivaniv waited 12 hours to cross the border into Poland.

The family was able to catch a flight into the U.S. – something Baczara says was only possible because Ivaniv had previously visited the U.S. with a visa. Baczara picked her sister up from the airport and took the family to St. Andrew the next day.

“I always thought that I’m missing on a lot of family events [living so far from Ukraine],” said Baczara. “Now I know that the reason why I’m here is that I could provide refuge for my family.”

Although Ivaniv feels she should be in Ukraine with the rest of her family, she said she’s empowered to help others by raising awareness of what’s happening back home.

“I don’t want somebody to feel sorry for me because I’m here safe,” Ivaniv said. “I want the world to understand that we need this help because this is a very cruel struggle. The battle for independence and battle for a future as a sovereign country.”

Baczara and Ivaniv are far from alone. Many parishioners at St. Andrew worry everyday about the safety of their family back home.

“You want to cry every time you see these pictures,” said Solomiya Gorokhivska, a parishioner who was born in western Ukraine and studied in Kyiv.

Gorokhivska’s mother came to visit in the days before the conflict reached a boiling point. Although she says she’s lucky to have her mother nearby, she’s anxious about her and her husband’s relatives.

“Every two hours I’m checking, ‘Okay, just give me two words. I don’t need you to talk to me long. Just so you are safe and you’re alive,’” said Gorokhivska.

As a longtime parishioner, Hanja Cherniak says the church and community are doing everything they can to support Ukrainians locally and abroad.

“People are very worried,” said Cherniak, who’s also the treasurer for the Holodomor Committee, a non-profit working to raise awareness of what’s been recognized as the genocide of Ukrainian people between 1932 and 1933 by the Soviet government. “We have been sending humanitarian aid, medications, and things to orphanages and parishes for years. So now there’s renewed focus.”

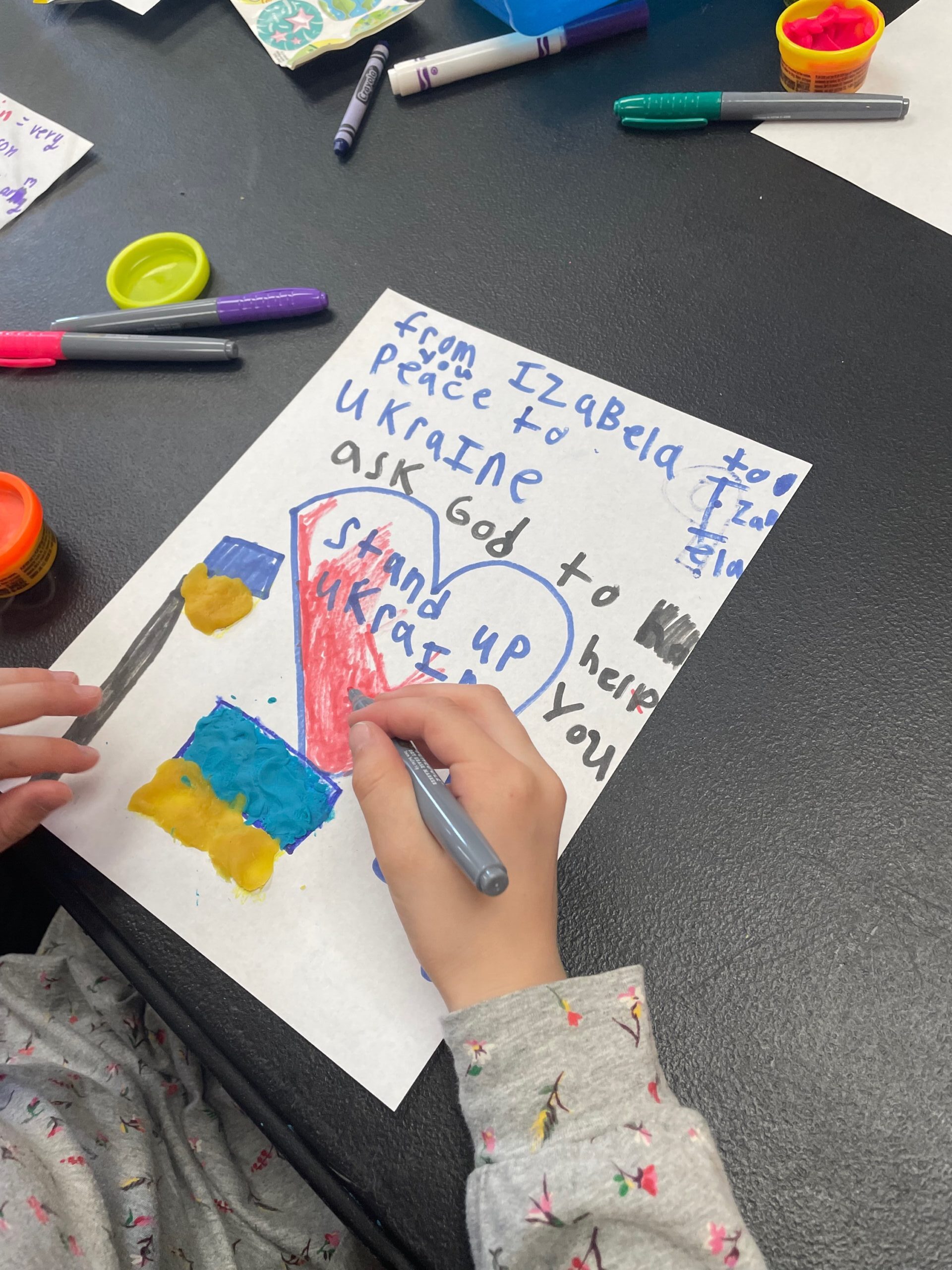

Among the support that parishioners are trying to send back are messages for soldiers and civilians. Katya Gramatova, who helps run the Sunday school, says they’ve been trying to teach the children about what’s happening.

“They’re working on projects or their expressions of what’s going on today,” said Gramatova, who was born in Slovakia near the Ukrainian border. “We plan to send it to either Ukrainian families back in Ukraine or the soldiers.”

While it’s hard to know what comes next in the war, Gorokhivska says St. Andrew has become more than just a house of worship. The community will continue praying – and working – for one another.

“It’s not just a religious institution,” said Gorokhivska. “It’s a community institution where Ukrainians can connect and get help.”

Héctor Alejandro Arzate

Héctor Alejandro Arzate