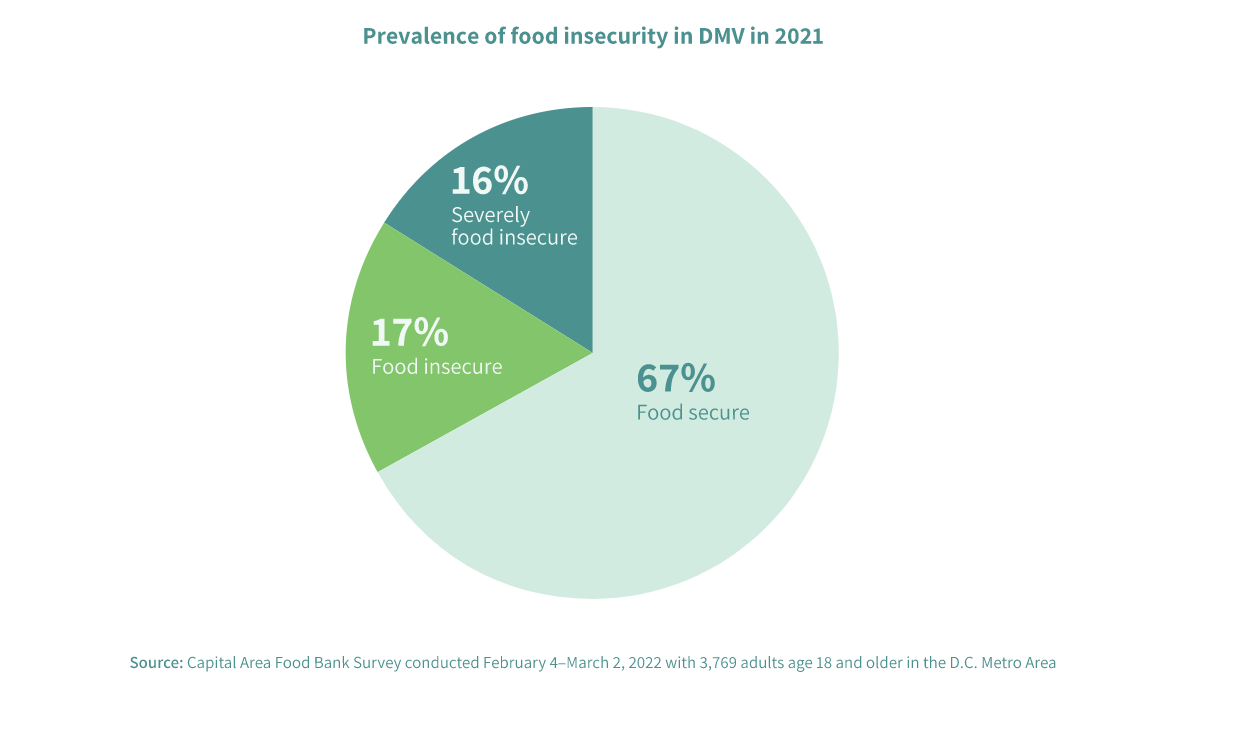

One in three D.C.-area residents was food insecure in 2021, according to a new study from the Capital Area Food Bank – underscoring the longstanding structural inequities that have only widened and worsened during the pandemic.

Capital Area Food Bank’s third annual Hunger Report, conducted in partnership for the first time with the National Opinion Research Center, a social research organization out of the University of Chicago, shows an intensifying hunger crisis in one of the wealthiest areas of the country. The study surveyed 4,000 residents in the D.C. region: D.C., Montgomery and Prince George’s counties in Maryland, and Fairfax, Arlington, and Prince William’s counties in Virginia, as well as Alexandria City.

Food insecurity, defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture as as a “lack of consistent access to enough food for an active, healthy life,” was most prevalent in Prince George’s County, where nearly half of all residents were food insecure. In D.C., 36% of the population reported food insecurity.

“This research just validates what we’ve been seeing all year long,” says Radha Muthiah, CEO of Capital Area Food Bank, which distributed 64 million meals in 2021, a record for the organization. “It’s disheartening in a few ways – not just [due to] the staggering number of individuals who are uncertain in how to plan for a meal over the course of a year, but it’s also disheartening because of the outlook, for them, doesn’t look promising, and the stressors that come with that as one tries to go about daily life.”

Because this year’s study used a different methodology than in years past, it cannot be compared directly to the 2021 report – which found, most glaringly, a drastic increase in the number of Hispanic families experiencing food insecurity in the D.C. region. Last year’s report analyzed the overlapping system failures that prevented food insecure families and residents — particularly Hispanic residents — from accessing service. Despite a number of local and federal assistance programs launched in the acute phase of the pandemic, including direct cash payments and a modification of the Supplemental Assistance Nutrition Program (SNAP), demand for these services was so high and often inaccessible that the most vulnerable residents fell through the cracks.

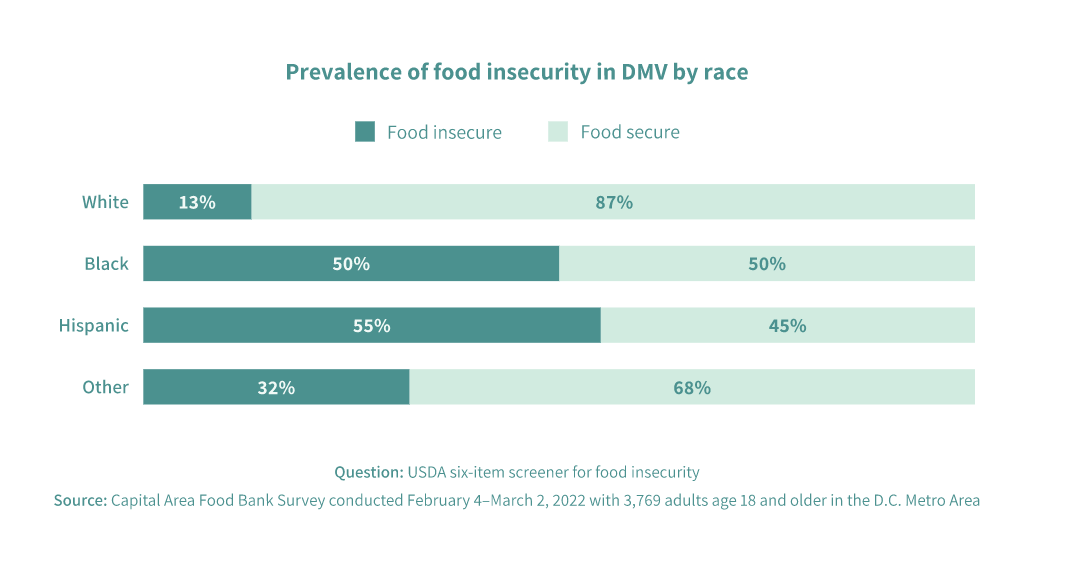

While this year’s report showed a slight decrease in the number of Hispanic families experiencing food insecurity, according to Muthiah, it still illuminates gaping disparities along racial and economic lines in the region (inequities that long predated the economic fallout of the pandemic), as COVID-era government assistance falls away and inflation rises.

“Although those disparities existed before the pandemic, the data underscore that the events of recent years have set these trend lines on a course for continued divergence,” reads the report. “This will have negative consequences for all of our region’s residents — not just those who are experiencing hardship.”

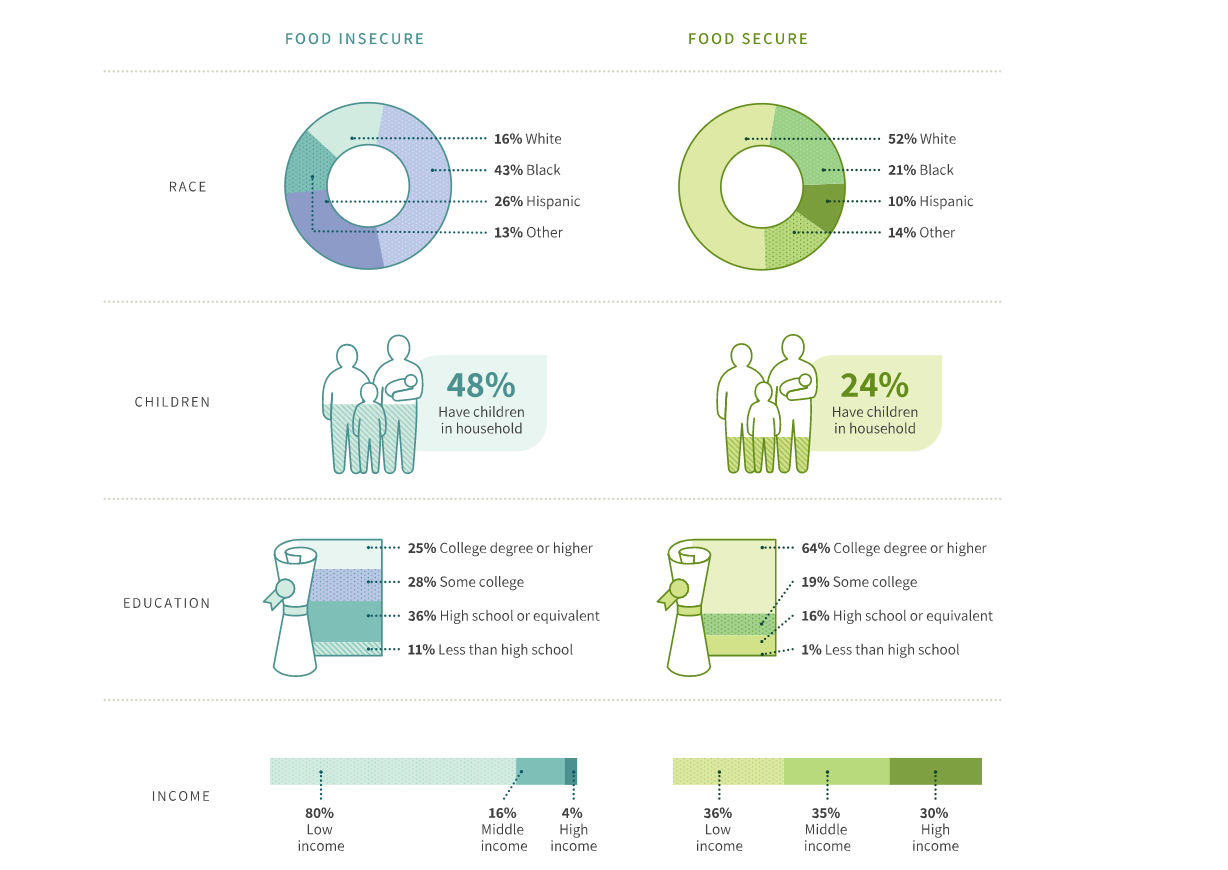

Among Hispanic respondents in the region, 55% reported experiencing food insecurity, and 50% of Black residents reported food insecurity, compared to 13% of white residents. According to CAFB, race and the presence of children in the home are the two strongest indicators for food insecurity: In 2021, households with children were twice as likely to be food insecure compared to those without. And while only 12% of white households were food insecure, nearly two-thirds of non-white households with children were food insecure.

“The numbers were just astronomically high, the level of and rate of food insecurity among people of color, and in particular among households with children,” Muthiah says. “These type of statistics should not be occurring in the Greater Washington region, the nation’s capital.”

While 77% of food insecure respondents were employed last year, nearly half said their total household income is lower than it was in March 2020, while only 18% of food secure respondents said they now made less. This financial strain bleeds into all other living necessities – nearly half of food insecure adults missed a credit card bill during the pandemic (compared to 9% of food secure adults), and 42% of food insecure households could not pay a rent or mortgage bill in the past two years, per the report.

Furthermore, residents experiencing food insecurity were twice as likely to believe that their household finances would decline over the next year — a gap in perception that stretched across race and income as well.

“If you miss a car payment, that leads to repossession that limits your transportation, you’re unable to get to your place of employment. Missing a [rent or mortgage] payment can lead to eviction or temporary homelessness. These short-term implications can lead to very dire long term consequences,” Muthiah says. “That’s what’s important for us as a broader community to understand and incorporate, as we think about how we can rebuild in a manner that allows everyone to participate — that means living wage jobs, access to education, utilization of government programs.”

The report offered a number of recommendations for both the public and private sector to address food insecurity — some that have been discussed time and time again. For private businesses, CAFB advocates for a living wage and paid sick and family leave for all workers; in the public sector, CAFB said local and state governments need to make sure that they’re making assistance known, and accessible. Only half of the food insecure population in the D.C. region is seeking any form of income assistance at all, per the report — a measure that could be driven by a number of factors, like a lack of awareness, a distrust of government, and complex or bureaucratic processes for receiving benefits.

The report comes as D.C. attempts to shrink the food desert that has spanned wards 7 and 8 for years. Both wards have just two full-service grocery stores, compared to 13 in affluent Ward 3 (with more on the way). This week, Mayor Muriel Bowser announced a tentative deal with Giant to bring a full-service grocery store to the long-vacant Capitol Gateway site on the eastern edge of D.C. in Ward 7, and the D.C. Council recently passed a bill that would allow grocers who open in wards 7 and 8 more flexibility on selling liquor.

In Prince George’s County, the jurisdiction most impacted by food insecurity, officials launched a task force during the pandemic to address food access issues. The group issued its first list of 11 recommendations earlier this year, including policy changes like issuing tax incentives to attract grocers to the county, and ramping up transportation for residents in rural and underserved areas.

“An uneven pandemic recovery that reinforces the existing systems and structures that advantage some members of our community more than others will ultimately be slower, and it will prevent the Washington area from reaching its full potential,” reads the report.

Previously:

Food Insecurity Among Hispanic Families Surged During Pandemic, Report Finds

Colleen Grablick

Colleen Grablick