Have you ever felt gaslighted by a Metro bus?

For about a dozen years, riders have used Metro’s real-time busETA website (or other third-party apps that use Metro’s data like Google Maps, Transit, and Citymapper) to track the real-time location of a bus and help decide when to leave the house. The rise of smartphones has made it easier and more convenient to make a bus trip as efficient and short as possible.

But sometimes the data reports a bus is on its way or has arrived at the stop and it’s not there. Other times riders say that the buses show up on the apps and disappear halfway through the routes. On the busETA site, a blue bus logo is a bus on the route with real-time GPS enabled. Gray bus logos are scheduled buses, but they may or may actually be on the route.

“When busETA notes that bus location information is based on scheduled data, it could be for a few reasons: when a detour or roadblock results in a significant deviation from the bus’s normal route, when onboard GPS equipment fails, or when a trip is cut due to operator availability,” Metro said in a statement. “Often, these buses are not in service or are prevented from servicing all or some stops on a route, and Metro realizes how frustrating that is for our customers. At the direction of the General Manager, bus operations are working on a technical solution to ensure busETA only displays buses that are verifiably in service for customers by the end of this year.”

The phenomenon is known as a “ghost bus” and it frustrates riders almost daily. MetroHero, a third-party app that uses Metro data, but also analyzes it, reported that about 11% of all scheduled bus stop never happened. Other local bus operators face the issues, too.

“It’d be great if WMATA did a better job letting riders know when a scheduled bus is canceled, but the deeper problem is that those scheduled buses are being canceled,” James Pizzurro, one of the founders of the app, said on Twitter.

Ben Harris rides the 62/63 which runs between Takoma and Federal Triangle in D.C. He’s often had buses not show up, which can double his commute time since he has to wait for the next bus in 25 or 30 minutes.

“It makes me feel like… bus riders are second-tier, and bus travel (is treated) as a means of last resort,” Harris said. “Imagine having a car-dependent commute, and unpredictably sometimes having to wait between 15-30 minutes just to be able to start your trip.

“That’s what being a bus commuter in D.C. can feel like.”

Harris notes the issue causes a cascading set of problems: waiting excessively for the next bus, and then that bus will be more crowded because so many people have been waiting for it. That bus will then have to make more stops because there are more passengers and will travel more slowly because of it.

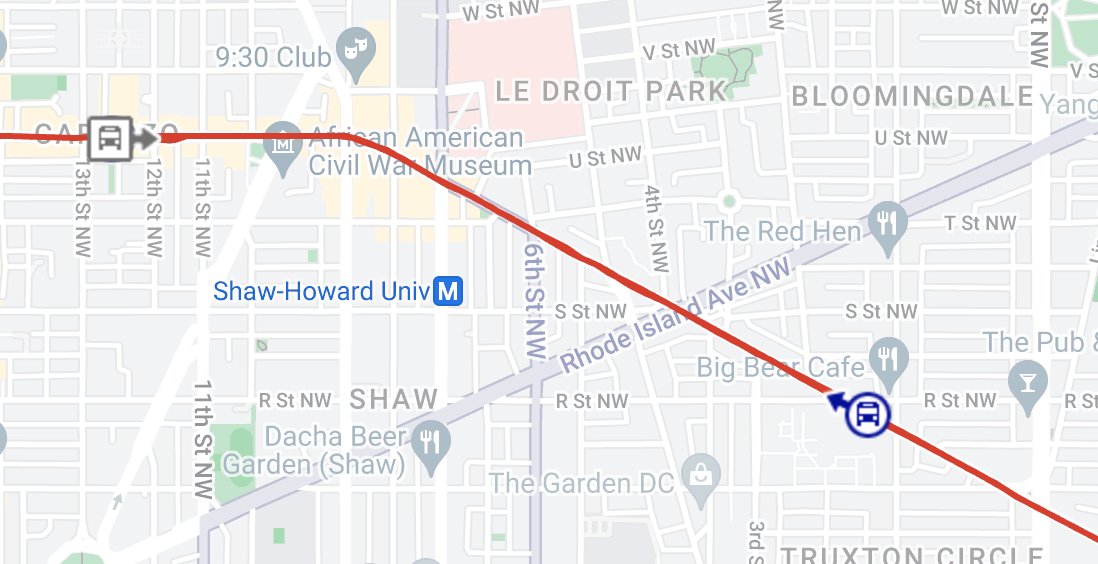

Other riders report the same issues on lines like the 90/92/96 that goes along U Street, Florida Avenue, and 8th Street, the crosstown H2/H4, the north-south S2/s9 on 16th Street, the G12 from Greenbelt to New Carrollton, and more. Some Twitter users reported ghost buses for nearly 20% of their trips.

WMATA board member Tracey Hadden Loh faced the issue last Saturday on the 96. She waited an hour with her 3-year-old that needed to use the restroom.

“It’s literally ruining someone’s entire day,” she said. “There are people all over the city waiting for the bus and then it doesn’t come.

“If we left someone waiting on a rail platform for an hour, it would be front-page news. So we really need to address bus service reliability.”

New WMATA General Manager Randy Clarke says he wants to fix some of the backend tech issues caused by an older software system by the end of this year or the beginning of next, to address bus ghosting.

“The idea that in 2022, our current software doesn’t allow us at a control center to delete a bus that is not filled in the schedule, and therefore it looks like what people call a ‘ghost bus,’ is not okay,” he said.

Clarke noted that the bus has often gotten short shrift in the past at Metro.

“Bus is very important (to the leadership team),” Clarke said. “A bus customer and a train customer are equal.”

“I do think we just have to be honest, I don’t know if culturally that has always been the case. And so we have a little bit of a hole to dig out of there.”

Bus ridership is often higher than rail (316,000 vs 280,000 trips on a recent weekday) and it serves people who on average make $30,000 or less and have no other option for travel.

While the tech side of things can cause confusion and frustration, part of the root of the problem is those canceled trips — whether it be for vehicle breakdowns, a last-minute operator out sick or late, or the bus operator shortage. Metro says it’s down 100 operators at the moment and is trying to recruit and train more by next spring.

Metro is also taking a longer view at fixing the bus system and is surveying riders for its year-long “Better Bus” campaign through Nov. 11.

Meanwhile, Clarke also wants to tackle another problem facing bus customers — blocked bus-only lanes in D.C. and elsewhere.

“We need people out of our bus lanes during rush hour, period,” Clarke said. “Now that means ticket or tow them… if it was up to me, I’d have my own wrecker, I’d be hauling people all day long.”

Clarke says WMATA staff vehicles have blocked the lanes, too, and promised offenders would be held accountable.

The bus lanes are meant to give buses priority since it carries more people than individual vehicles. But it’s a complicated web of bureaucracy as the localities like D.C. or Alexandria that actually install and monitor the lanes are responsible for keeping them clear. D.C. is launching a pilot program using cameras to ticket drivers who use the bus lanes when they’re not supposed to.

Jordan Pascale

Jordan Pascale