This time last year, D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser proclaimed November 16 “Clockboyz Day.” The holiday was named in honor of a Watkins Hornets Youth Association football team for their athleticism, sportsmanship, and commitment to preparing Black boys to be leaders in the city. The team had been preparing to celebrate the holiday for weeks.

But now, the boys and their coaches are preparing for a funeral instead. Fourteen-year-old Antione Manning, who played with the Clockboyz throughout his middle school years, was fatally shot on Halloween. He had previously been shot on the same block – the 2600 block of Birney Place Southeast – a few weeks prior. Police told reporters the attack that killed him was likely targeted; authorities are looking for a silver sedan captured on surveillance footage near the location of the shooting.

“It’s just heartbreaking,” said Charles Holton, a Clockboyz coach.

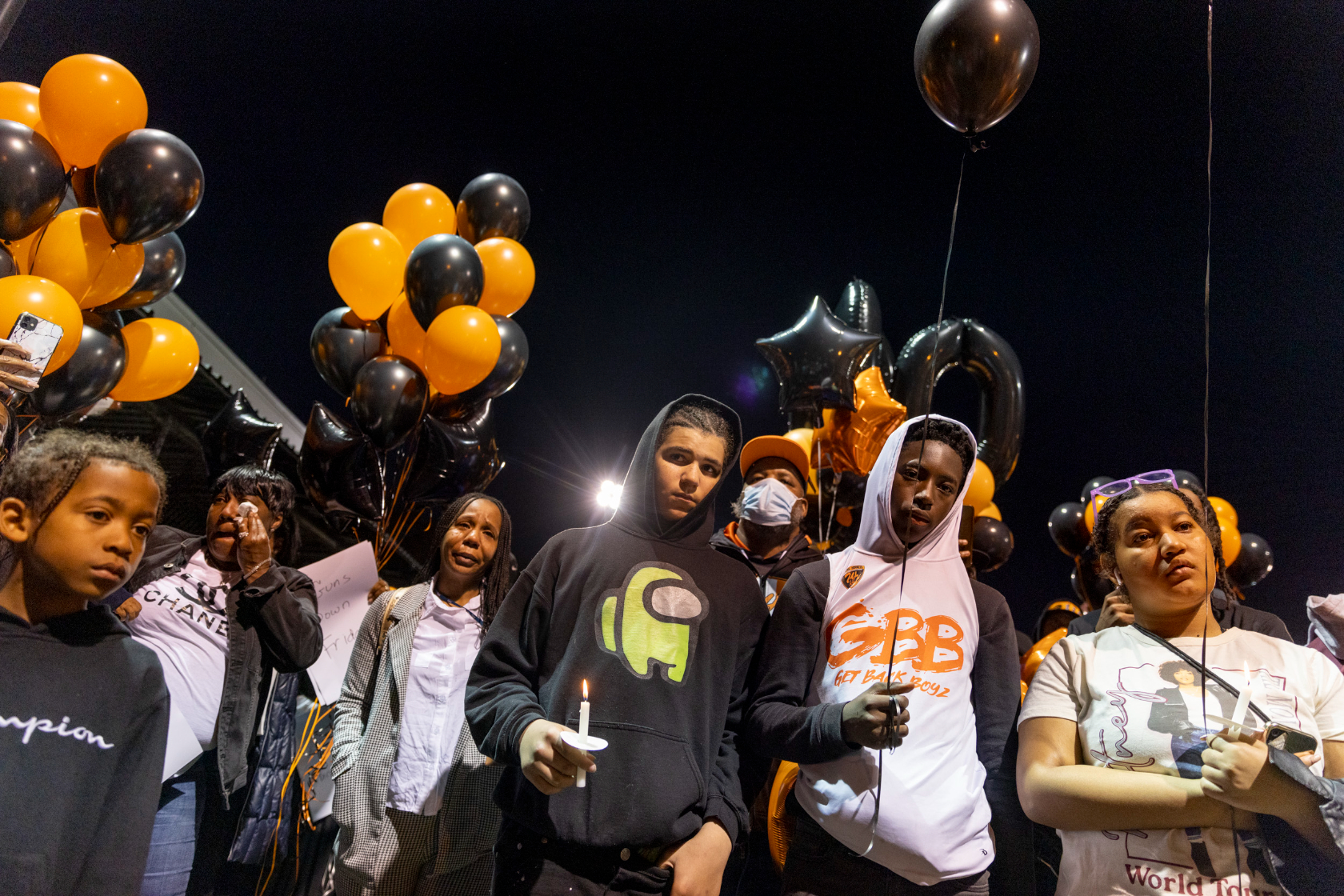

Antione’s approximately 35 other teammates, along with their families, coaches, and about 100 others from across D.C.’s youth football community, gathered on Thursday night to honor Antione’s life. They shared memories, prayed together, cried together, and released balloons in his honor at the Watkins Elementary School field in Capitol Hill, where Antione practiced with the Clockboyz four nights a week for years.

Friends, family, and coaches were still in shock at the loss of Antione, affectionately known as “Doodie” (a nickname his mother gave him when he was born) or “Twon.”

Chuck Whitley, 14, grew up with Antione in the Barry Farm neighborhood of Southeast D.C. Antione was always over at his house, he said.

“He was a cool kid,” Chuck told DCist/WAMU. “He was good. He was loving. He was fun to be around.”

Chuck was among a group of Antione’s teammates and friends who spoke at the vigil. He said he had been texting with Antione in the hours before he was killed, and the two had seen each other at school that day.

“Before he left school, I told him I love him, stay safe,” Chuck told the crowd.

He said they were failing their English class earlier this school year, but together they brought their grades up to a B. Chuck described his friend’s ambitions: Antione was just telling him he wanted to transfer to a private school, Archbishop Carroll, and play football there.

In their speeches, Antione’s teammates described how much he cared about his team. One boy told a story about how Antione cried when he dropped a ball during a championship game in Florida.

“He wasn’t even crying because he dropped it. He was crying because he felt like he let down his brothers,” he said. “After the game, we went over and held him in our arms. Twon was one of us.”

Others described their shock, confusion, and devastation at Antione’s death. One boy told the audience that after the Clockboyz’ last season ended, he prayed every night that each and every one of his teammates would stay safe.

“My question is just why. Why does this keep happening?” another teammate of Antione’s asked the crowd.

In total, 175 people have died by homicide in the District this year, according to police.

The Gun Violence Archive, which tracks shootings across the U.S., says 16 teenagers have been killed by gunfire in D.C. so far this year, and more than 60 teens have been injured in shootings. In October alone, 15 teens were injured in shootings, and two were killed.

In particular, the D.C. region’s youth football community is still reeling from the losses of two other young boys — 8-year-old Peyton John “PJ” Evans, who was killed by stray gunfire in Prince George’s County last year, and 11-year-old Davon McNeal, who was caught in crossfire and killed in Southeast D.C. in 2020.

Coaches told DCist/WAMU that the year after Davon was killed, the Clockboyz won a national championship with his number – 3 — printed on their jerseys.

Davon’s coach, Kevin McGill, spoke at the vigil for Antione and prayed before the crowd.

“I’m asking you that you touch his parents, Lord God, that you touch his family, that you comfort them … in the late night hour when the memories come, when they no longer can talk to him, they no longer can feel him, when they no longer can hear his voice,” he prayed. “We’re speaking love over these kids, Lord God, that you protect them…that you cover them, that they won’t be subject to this no more, that we will not be here, doing this, over and over again.”

Antione’s mother, Shienna Manning, cried as she stood at the front of the vigil. Antione’s uncle, Vincent Manning, told DCist/WAMU that she would be declining interviews about her son for the moment. Manning described his nephew as an “incredible kid: loving, kind, caring, ambitious, hardworking.” He said that during first year on the Clockboyz, Antione made it to a starting position.

And, his coaches added, during a national youth football championship game in Florida, he made the game-winning play.

His coaches said he was always one of the fastest kids on the field. And they said he worked hard. One coach, who preferred to go by the nickname Coach Bob, described how Antione would always ask him and the other coaches to time him on sprints so he could get faster.

Delante Hellams, known to his athletes as Coach Lody, used to drive Antione to and from practice almost every day. He said that during the early days of the coronavirus pandemic, when school buildings were closed and learning went remote, Antione would text him every morning with a photo of his computer screen to show that he’d logged on to school on time. He’d send his coach texts when he brought his grades up.

“He was so proud,” said Hellams. “He was a great kid.”

This story was updated to reflect the correct spelling of Antione Manning’s name.

Jenny Gathright

Jenny Gathright Tyrone Turner

Tyrone Turner