A new behavioral health clinic for uninsured, underinsured, and Medicaid patients opened in Loudoun County this month with the hopes of expanding mental health benefits to some of the thousands of Virginians currently falling through the cracks of the state’s struggling mental health system.

The rate of adults in Northern Virginia struggling with anxiety and depression has soared since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, with 28 percent dealing with symptoms in 2021. In 2019, that rate was just eight percent, according to a report by the Community Foundation for Northern Virginia. According to the same report, existing services aren’t sufficient to keep up with the growing demand: of the 370,000 people in the region who want therapy, the foundation estimates that 39 percent aren’t able to get it.

“People are still struggling with PTSD coming out of the pandemic, [as well as] depression, anxiety, social phobias, not being comfortable around people — all kinds of kind of mild to moderate mental health diagnosis,” says Karen Berube, the Chief of Community Health and Health Equity Senior Vice President, Inova Health System. She adds that they’ve also seen an uptick in substance use since the pandemic started.

Located in Leesburg, right next to an Inova Emergency Room, the outpatient clinic was quiet last Tuesday morning, with empty therapy rooms painted in soothing blue tones and decorated with calming artwork. The site is focused on short-term therapy, offering 10-12 weekly or biweekly sessions for clients, with plans to expand to group therapy in the future. For now, the clinic has two therapists on staff but is planning to hire up to six to start, and hopes for more if demand increases.

Berube says they’re hoping to target adults without insurance who aren’t in an acute crisis but do want help with their mild to moderate mental health struggles. While most experts agree that mental health services across the board leave a lot to be desired, Berube says this group in particular tends to get left behind, potentially increasing instances of more dire mental health problems down the line.

“If you’re starting to feel down or you’re starting to feel like it’s just a struggle to get through the day, my hope is people will know about this place and they’ll come here and that’ll prevent a hospital admission,” says Berube. “You get the care you need before it escalates to a crisis.”

Elizabeth Hughes, the Senior Director of Insight Region at the Community Foundation for Northern Virginia, agrees with this analysis, adding that in Northern Virginia people with milder symptoms are often left to wait because the limited providers that do exist are usually scrambling to help people facing emergency needs.

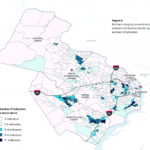

“There is a demand that far exceeds supply, and there are long waiting lists and individuals who are not in that very urgent state need to find resources elsewhere,” says Hughes, who published a report capturing gaps and barriers to mental health access in Northern Virginia for the foundation.

The clinic opens at a time when Virginia is facing staffing shortages and overcrowding at mental health institutions, leading to threats of closures and reductions in capacity that would further strain an already overburdened mental health system. Five of Virginia’s state-run mental hospitals were ordered to reduce capacity and consolidate staff last year – a decision that was temporarily reversed shortly after, according to Northern Virginia Magazine. Last year, 108 staff members quit from the Virginia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services after staff and patients reported assaults at the facilities.

While Virginia ranks 9th in the country for spending on hospital-based care, it’s 39th for community-based services like outpatient therapy, counseling, and psychosocial treatment, according to The National Association of State Mental Health Providers.

Access is even worse for uninsured and Medicaid patients, with Hughes’ research finding that only 4% of psychotherapists in Northern Virginia who are registered on Psychology Today accept Medicaid.

“Half of mental health professionals, of therapists in Northern Virginia don’t accept any kind of insurance which means that people are paying out of pocket,” Hughes says. Costs can be up to around $215 a session without insurance, according to her report, with a year of therapy costing $11,000.

It’s a problem that Berube hopes the clinic will start to chip away at. According to Inova’s Loudoun County Health Assessment, a one-year study that included focus groups and data analysis, there are 22,300 uninsured people in Loudoun County.

While patients without a car will struggle to access the Leesburg location, which only has one bus stop nearby, Berube says they expect most in-person patients will be coming from rural communities by car and that they hope to expand their reach through telehealth services.

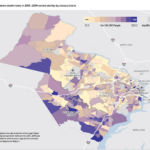

While Loudoun is the wealthiest county in the nation, Berube says major disparities exist.

“So there’s very, very wealthy families and communities here. But there’s also the extreme opposite where we have very low socioeconomic status and the needs are not being met in those communities,” Berube says.

A 2017 report by the Northern Virginia Health found that life expectancy can vary by as much as 10 years across the county, with predominantly Latino populations experiencing factors that widen the gap, such as high rates of poverty and low rates of education.

Hughes says that nationally rural areas often have mental health provider shortages.

Berube hopes their location in Leesburg, with its proximity to rural areas and a rising immigrant community, will help them reach these underserved populations.

“It’s because the surrounding areas have a lot of workers that are immigrants and from the immigrant community, and their needs are not addressed in the more rural areas,” said Berube.

Sunnie, a therapist at the clinic who only gave her first name for confidentiality reasons, says she has a personal connection to the work because she’s part of an immigrant family herself. Because this is a patient population that in many cases hasn’t ever accessed mental health resources before, she says that so far sessions have been focused on “psychoeducation,” or learning the basics of how therapy works.

“Most of my clients so far have been first time counseling experience. And so they come [in] very anxious and nervous and curious about the process and [I’m] just kind of walking them through what counseling is,” Sunnie says.

A major challenge the clinic will face is reaching the patients who need their services. While the addition of a clinic is likely useful for Northern Virginians, it may not help with what Hughes says is the biggest barrier to mental health services: whether patients are actually able to access existing services.

“My data [doesn’t] suggest that there’s a shortage of licensed mental health professionals. It’s more that there are pretty substantial difficulties with people accessing these resources [that are] available,” Hughes says, adding that barriers include difficulties finding a provider and trouble managing costs and logistics.

Other mental health initiatives are being introduced across the region in an attempt to address disparities. Virginia started a new mental health hotline this year (though it has already faced criticism about capacity given the scale of the problem). Prince William County is considering plans to open a new mental health crisis center. Alexandria introduced a program that sends mental health workers with police officers on calls, and Governor Youngkin may be poised to introduce a mental health agenda.

Hughes says she’d like to see an increase in the supply of proactive “first-responders,” or people already located in communities that lack access to mental services who can help patients navigate the often complicated system and connect them to care. Hughes adds that the first person a patient reaches out to about mental health struggles may not be a doctor or therapist. In many cases it’s more likely to be someone in the community they already know, such as a church leader.

“People who feel really comfortable going deep and talking to people about what’s going on with their lives so that it doesn’t escalate into something that needs formal mental health intervention, so not just having that clinical component and with all professional staff,” says Hughes.

Berube says building trust within the community is a challenge they’re keeping in mind as they think about ways to spread the word about the clinic, especially because the patient populations they’re trying to reach often has low levels of trust in the healthcare industry and fears unexpected costs.

“That’s the big thing is people get afraid if they come in, they’re going to get a bill and they’re not,” Berube says.

She believes their location in Leesburg, however, will help with outreach.

“By putting our clinics and programs in the neighborhoods, we become part of that neighborhood. And hopefully that will build the trust,” Berube says. “They’ll come in and they’ll meet the therapist and they’ll know that we’re here for you.”

Aja Drain

Aja Drain