From the joyful celebrations in honor of the first Black woman confirmed as Supreme Court Justice of the United States to the angry protests against the Dobbs v Jackson decision, our cameras caught and shared a wide range of the human experience in the D.C. region this year.

There were intimate moments, like the one shared by expectant mom Tsedaye Makonnen (pictured above) with her team of midwives from Mamatoto Village, all of them listening to her baby’s heartbeat during a home wellness visit.

Mamatoto Village is a Black birth worker collective that offers pre and postnatal wraparound care for primarily Black and immigrant women residing in Wards 7 and 8. This year they opened a new clinic on Sheriff Rd. NE.

“I intentionally wanted to work with Black practitioners, because that’s who I feel the safest with,” Makonnen said. “Culturally, there’s just an understanding and a level of support that they can provide that other health practitioners can’t.”

Joy was the word of the day as Regina Langley, middle, of New Jersey, celebrated with friends on the steps of the Supreme Court after the full U.S. Senate confirmed Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson on April 7. Brown Jackson, who previously served on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, became this year the first Black woman confirmed to a Supreme Court Justice seat. DCist/WAMU stories looked at Brown Jackson’s background, the nomination hearings and the celebrations on the Supreme Court steps after the historic vote.

Samuel Price, 14, gets a breathing treatment every morning at his D.C. home in order to help open his lungs and get more oxygen into his system. He’s one of the more than 100,000 individuals in the United States affected with sickle cell, a disease that primarily affects the African American community.

Price was one of the voices highlighted in our in-depth story about sickle cell disease in the D.C. region — especially how it affects Black families in Prince Georges County, Md. “If you just imagine, like, somebody scratches you and they rip skin off, it’s similar to somebody scratching the skin off,” he said about the pain of his condition.

Hundreds of protestors gathered outside the Supreme Court following the justices’ decision to end the constitutional right to an abortion in the United States on June 24. Abortion rights supporters banged on drums and led chants, including, “Never again, we won’t go back!” and “What do we want? Choice! When do we want it? Always!”

“Today I’m fucking angry. We have been betrayed yet again by the government that we have put in power,” said Afeni, a core organizer with Freedom Fighters DC, one of the groups rallying protesters to the court.

As part of its coverage of the aftermath of the overturn of Roe v Wade, DCist/WAMU visited with Black community members in Wards 7 and 8 to hear their perspectives on the changes in the legal status of abortions.

“They [Black communities] will be affected because it’s already limited resources for them to get abortions,” said Mariah Delbe. “So the fact that there’s more people trying to come to D.C., there won’t be anything left for the people who’s poor and who can’t get resources because they’re coming in. They’re taking all of it because they’ve got to come to D.C. just to get an abortion. So that’s how I feel about that.”

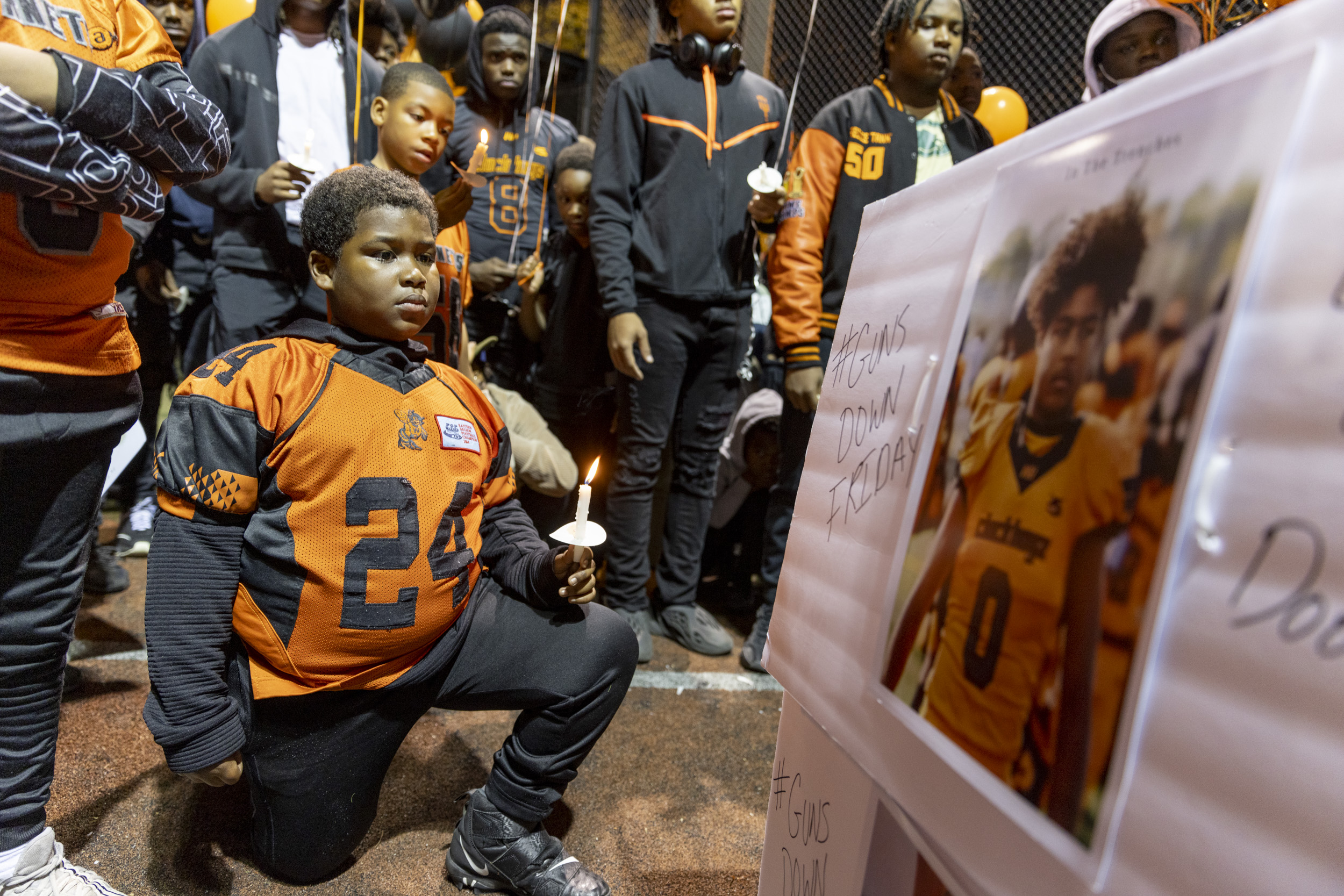

A community in mourning gathered to honor the life of Antione Manning, 14, on November 3. Manning, who played for the Watkins Hornets Youth Association Clockboyz, was shot and killed on Halloween night. Antione’s teammates, along with their families, coaches, and about 100 members of D.C.’s youth football community shared memories, prayed together, cried and released balloons in his honor.

“He was a cool kid,” said Chuck Whitley, 14, a friend of Antione. “He was good. He was loving. He was fun to be around.”

“My question is just why. Why does this keep happening?” another teammate of Antione’s asked the crowd.

DCist/WAMU went to Wunder Garten in Northeast D.C. for the U.S. v. Iran World Cup soccer match watch party. About 300 soccer fans were there to drink beers and root for both teams, though the crowd leaned decisively in favor of the U.S. As the national team scored its first goal against Iran, the crowd erupted into a chant: “USA! USA! USA!”

Youssef Ibrahim hugged his father Hesham Ibrahim, right, and his brothers, Adam Ibrahim, 7, below, and Abdaloah Ibrahim, 10, on left, after the USA won the match 1-0.

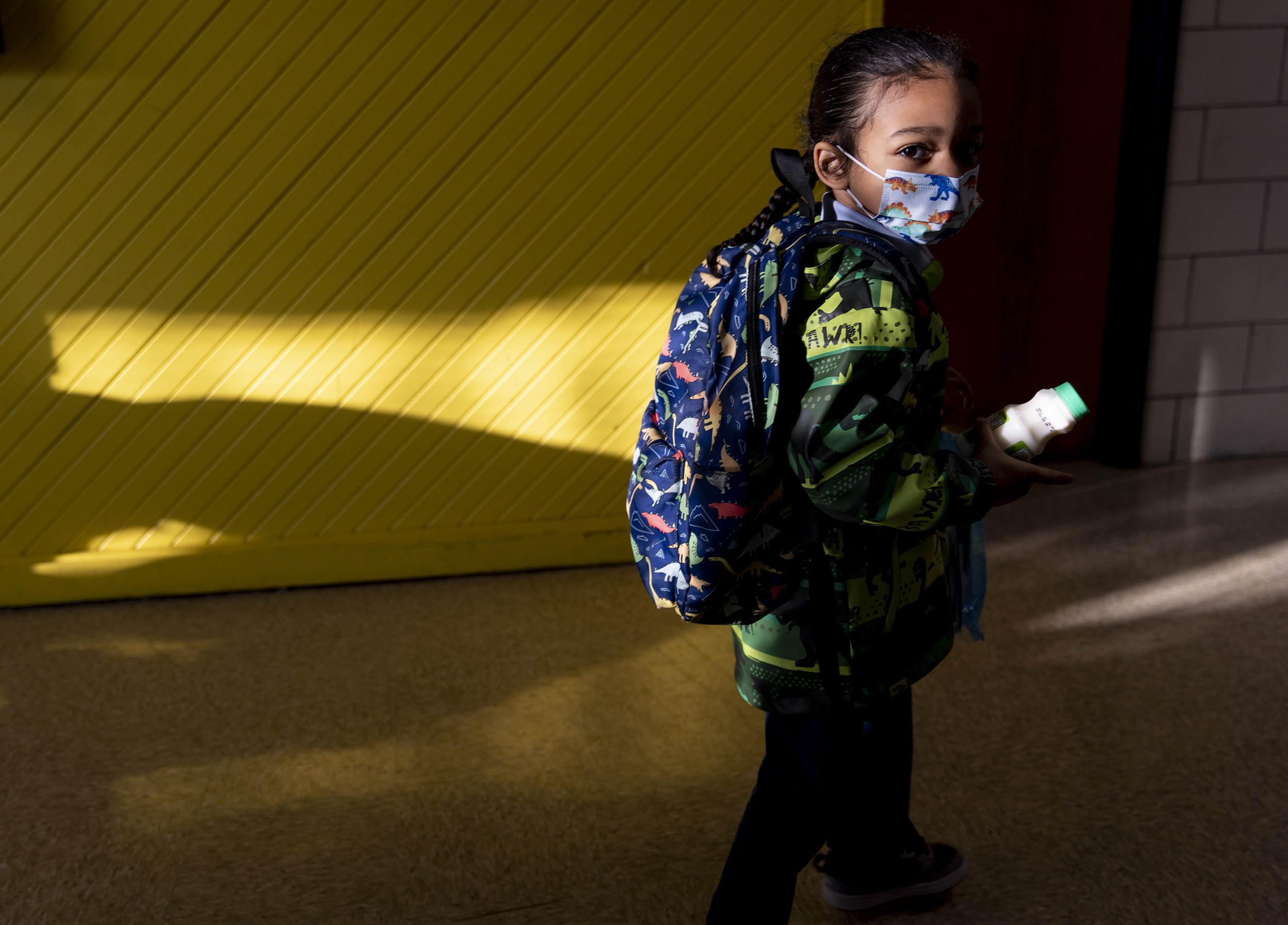

DCist/WAMU visited Prince George’s County schools in the spring of 2022 to look at how the county was evaluating its in-person education and continued mask policies for students.

Families and educators in the county say a careful strategy around in-person classes has built trust in the district, helping avoid the clashes over masking and in-person learning that have divided other communities.

“Because Prince George’s was hit so hard, our community has really embraced this conservative approach,” said Donna Christy, president of the Prince George’s County Education Association, a union that represents more than 10,000 educators. “I think we made the best of a really bad situation.”

“Some adults won’t just believe in us,” said Kevin Mason, 16. “They think we’ll grow up and be some type of demon, killers, or something like that, but that’s not what we really are. We’re trying to build something.”

For this edition of Voices of Wards 7 and 8, DCist/WAMU spoke exclusively to young people who live or go to school east of the Anacostia River about the kinds of support they feel they need to achieve their goals.

Billie Krishawn, who played Mamie Till-Bradley/Simeon Wright/Carolyn Bryant in The Mosaic Theater Company’s production of “The Till Trilogy,” sings as she and the rest of the cast practice the music for the play. DCist/WAMU attended a rehearsal for the ambitious project, made up of three plays about Emmett Till by Ifa Bayeza.

“You see a lot of the same names come up when the grants are announced, and that’s sad,” said Seshat Walker, a longtime D.C. playwright and poet, who created The aSHE Fund, which grants $2,500 to five local Black women each year to help them complete a creative project, to counter what she sees as disparities in arts funding.

Walker believes that the lack of prominent cultural spaces in neighborhoods like hers — Deanwood, in Ward 7 — contributes to a lack of visibility for individual artists who live there, and thus, less arts funding.

“There’s no movie theater on my side. There’s no place to go see a concert on my side. There’s barely a bar, like a good, decent bar to hear live music,” Walker says. “So we don’t have those rich spaces for people to gather and experience art. So when you don’t have that, possibly, the city is like, ‘Well, if there are no spaces there, then there are no artists there.’”

Executive director Maya Davis poses for a portrait in the Riversdale House Museum in Riverdale Park, Md. In the background are reproductions of paintings of Calvert family members who owned and lived in the house. Davis and her staff are trying to introduce more of the history and stories of enslaved people who lived at the house, as well as trace their genealogy. DCist/WAMU toured the museum with Davis for an in-depth look.

“It’s kind of hard to go up against real. And, you know, we keep it real,” says Sheldon Scott, a celebrated performance artist from the deep South who five years ago accepted the position of the Eaton Hotel’s first director of culture. His efforts to make the hotel a cultural beacon for the Black community, complete with art shows, film screenings, and spaces where activist groups “feel safe,” as he puts it, earned him a new title as the brand’s first global head of purpose — a position in which he focuses on the company’s “triple bottom line:” its financial, social, and environmental impact on a larger scale.

Tyrone Turner

Tyrone Turner