On a breezy, bright Saturday afternoon in mid-February, the tenants of 1355 Peabody St. NW rallied in front of their apartment building to lobby for better living conditions. Their landlord, Khan Properties, organized a competing party just steps from the front door. While dozens of residents and housing advocates bleated their frustrations into a megaphone, a pair of reps from Khan shuffled uncomfortably behind a fold-out table, cranking music on their speaker to drown out the noise. They had tiny sandwiches and a couple of metallic balloons. They also brought a security guard.

The guard’s presence was ironic, attendees said, since a 2020 shooting down the block – at a building also owned by Khan – left two teenage boys, a 16- and 17-year old who both lived in Khan properties, dead. Residents of the Peabody complex have asked for better security at their building ever since, but it wasn’t until Saturday, in front of cameras and crowds and an appearance by Ward 4 Councilmember Janeese Lewis-George, that management installed a guard.

“We’ve had enough. We are the forgotten building,” says Melesech Gelaw, a 41-year-old mother of two and D.C. Department of Human Services employee whose mother first moved into the building in 1998.

At least 35 families at 1355 Peabody St. NW – more than 60 percent of the building – are now withholding their rent from the company to protest what they call inhumane living conditions, Paige Dennis, an organizer with the tenant group Stomp Out Slumlords estimates. Khan owns four complexes on that block alone, as well as four more just a handful of blocks directly north. (Dennis believes they own even more, with at least 12 buildings in their portfolio.) The owners, Saifur and Monna Khan, have operated some of the buildings for decades; many of their tenants are lower-income seniors and immigrants from Latin America and East Africa with limited proficiency in English. (The Khans declined repeated requests for comment on this story.)

Tenants at 1355 Peabody tell DCist/WAMU that while poor housing conditions have persisted for years, the treatment they faced at the hands of their building’s property manager and owners throughout the pandemic precipitated a reckoning among them. “Everybody is scared. They’re scared of losing their homes. And at this time they’ve lost their jobs,” Gelaw says. “It took us meeting every Wednesday for a couple of months for us to kind of say, OK, let’s [strike].”

While she says the Khans were initially receptive to calls about property fixes, by the mid-2010s, their attention began to wander. She recalls fourth-floor tenants whose electricity went out, requiring them to walk around with flashlights and charge their phones in the basement utility room. The building had such a severe bed bug infestation that Gelaw tossed her toddler sons’ beds, buying a king-sized mattress for the entire family to sleep on so she could more easily inspect and clean it.

During the pandemic, as many of the residents lost their income, Gelaw began helping fellow tenants apply for rental assistance with STAY DC to catch up on bills. But in July 2021, a mail carrier with the U.S. Postal Service refused to continue delivering mail to the building, claiming that the boxes weren’t maintained securely. Gelaw and other tenants tell DCist/WAMU that people were unable to access critical mail, including medications and recertification paperwork for food assistance and health care. Gelaw herself didn’t receive immigration forms she needed. (In January, building managers finally reinstalled a functioning mail room.)

“Everyone stays in the house now [because of the pandemic]; everyone is cramped up. We don’t leave the house anymore, we stay in the home. And it becomes more aggravating to be living with mice and your children at the same time, and roaches,” Gelaw says. Tenants took it upon themselves to hire pest control, seek out food assistance and buy additional cleaning supplies. “Anything we needed, we were helping each other. It’s like we didn’t exist to [management], we were just living there. …. We were facing literally death. And the only worry you have is, [do] we pay our rent.”

They weren’t the only Khan tenants with complaints. A 2016 lawsuit filed in D.C. Superior Court by Kassahun Workneh, a Khan tenant at 1451 Sheridan Street NW, sought compensatory and punitive damages from the Khans over the conditions in his home. Workneh alleged that he and his family suffered emotional distress after persistent rainwater leakage caused the roof in his living room to collapse – a problem he claims he reported to the property manager roughly once a month for years. Coupled with a heater that routinely stopped working in the winter and a persistent infestation of cockroaches, Workneh told the court that he “was too embarrassed to invite guests into his apartment.” The Khans entered a confidential settlement with Workneh after court ordered mediation.

But poor conditions at the Sheridan property – along with yet another Khan building at 1450 Somerset Place NW – persisted, and former D.C. Attorney General Karl Racine filed suit in the summer of 2021 against the Khans’ management company over its alleged failure to “maintain the properties in safe and habitable conditions, leading to serious threats to the safety of tenants.” Racine’s team secured a $2 million settlement payment from the Khans’ companies, a portion of which will go to tenants as restitution. The Khans were also required to hire an armed security guard for the buildings and to install bars on windows of basement and ground floor units.

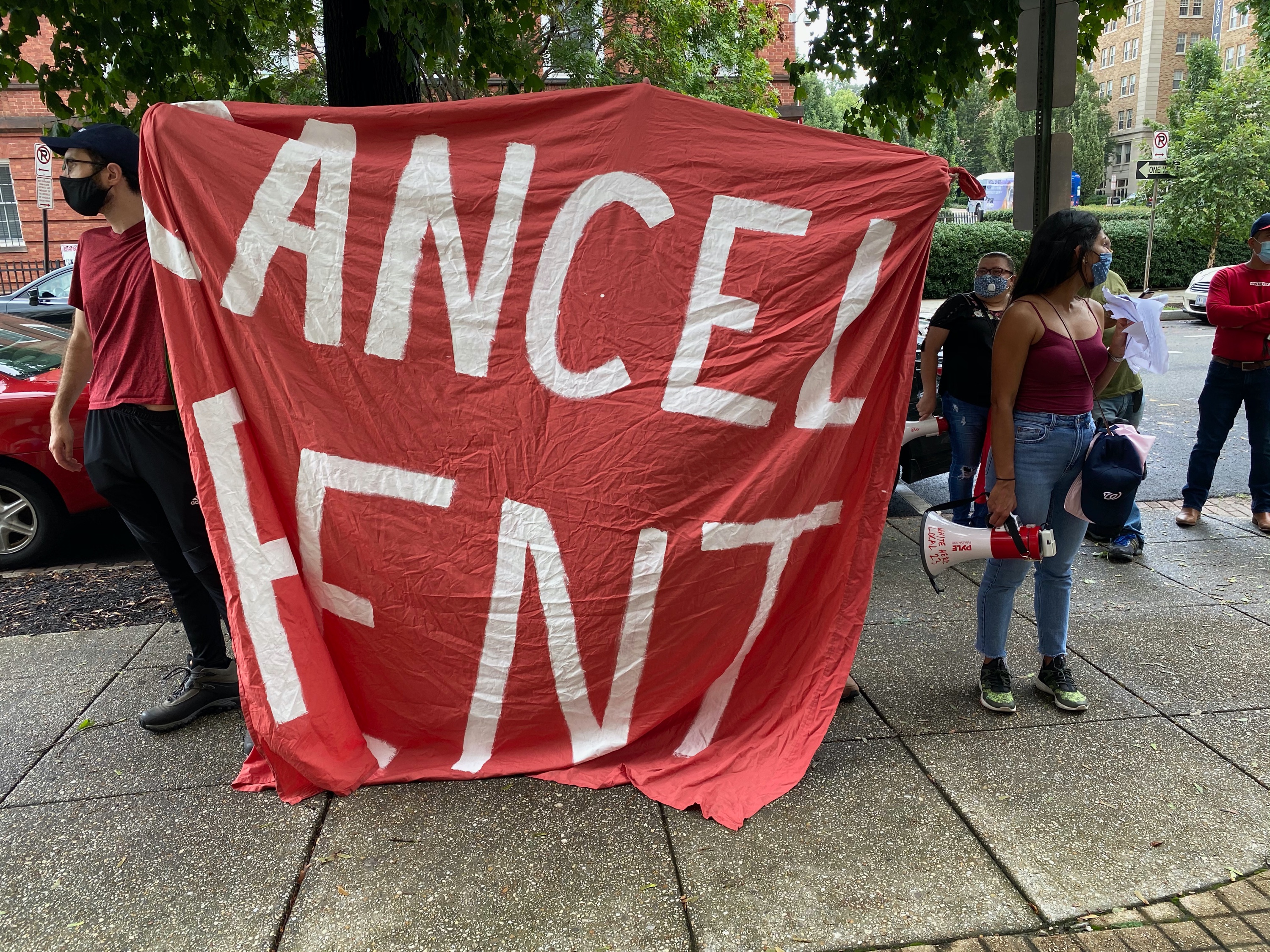

While the 1355 Peabody tenants just down the street had a very active WhatsApp channel dedicated to commiserating over goings-on in the buildings, they never had the appetite for going public with their concerns – at least, not in the way of the Somerset and Sheridan tenants, whose rent strike against the Khans precipitated Racine’s case against them. But in November of 2022, fed up with the mail debacle, Gelaw and her fellow residents decided they had enough. They were officially on rent strike.

Rob Wohl, an organizer with Stomp Out Slumlords who helped launch the group’s rent strike efforts, estimates that the group has helped launch strikes in at least 22 buildings across D.C. since the beginning of the pandemic, many of which occurred in Columbia Heights and Brightwood Park. Those strikes have led to material wins, whether in the form of building repairs, as was the case for the Sheridan and Somerset tenants, or rental relief, as was extended to some tenants in the notorious Park 7 complex on Minnesota Ave. NE.

Coupled with the concessions secured from Racine’s settlement agreement at the Sheridan and Somerset properties, Dennis and Eleni Reynolds, another Stomp Out Slumlords organizers who works with the Peabody tenants, say the group’s organizing has helped drum up interest in direct action at other properties in the neighborhood.

In Brightwood Park especially, they believe residents of the neighborhood have bonded through shared experience. More than 60 percent of people who live in the greater Brightwood Park and Shepherd Park area – in a tract of land D.C.’s planning office calls Rock Creek East – are African American, and 21 percent are Hispanic. Many of these residents are recent immigrants and might not know what kind of housing conditions they’re entitled to have.

“Landlords are relying on the fact that a lot of these people are recent immigrants who don’t speak English and don’t know that they have rights as tenants,” Reynolds says. “Now people are seeing it pay off – that you can organize or take your landlord to court.” Dennis adds: “Being like a tight knit immigrant community, there’s a lot of community trust, which really is critical for something like a rent strike or for organizing. When you know your neighbors and trust your neighbors, you can even go a lot farther.”

The area is also at what Wohl believes is a “tipping point” for housing stability. With major redevelopment underway at the former Walter Reed Army Medical Center, residents worry that climbing property values will make the neighborhood more competitive and less affordable – and that as housing providers try to realize their properties’ value by selling them, renters will have to deal with the fallout.

Despite the Peabody tenants’ unity in their strike, Gelaw is still worried about facing retribution from the Khans. In January, Gelaw says, Saifur Khan hand-delivered a letter to Gelaw falsely claiming that she owes nearly $31,000 in back rent – since November of 2017 rather than November of 2022, when she began her rent strike – and urging her to “pay or quit.”

“That means you want me to move so you can shut me up,” Gelaw says. “It sounds like a beautiful idea. But I can’t allow that.”

Morgan Baskin

Morgan Baskin