For Susan Cook, her backyard garden in Takoma is how she connects to the world and her community.

Although it can become a little dormant in the winter, she still usually has hardy greens like mustard and collards. When the weather gets warmer, her yard grows lush with strawberries, blueberries, black raspberries, figs, and more. Cook even gets plants and flowers like goldenrod, aster, beebalm, and swamp milkweed that attract bees and hummingbirds. And just like the pollinators that partake, Cook says the harvest is shared with her neighbors.

“To me, food is freedom,” says Cook, who works for the Montgomery County parks department.

That belief about community and freedom was planted in Cook’s mind early on in her life. Despite being born and raised in Detroit, both of Cook’s parents were from D.C. so she grew up hearing many stories about her family’s roots in the region. But the one that has resonated most with Cook, and inspired her love of gardening, is about the life of her fourth grand aunt – Alethia Tanner.

Tanner was a woman who was enslaved but was able to grow her own vegetables and sell them at a market in what’s now known as Lafayette Square. In 1810, she purchased her own freedom for $275. Years later, Tanner saved enough money to free more family members, including her sister, Laurana, and her six children. To Cook, Tanner’s story has more than inspired her.

“I do feel like Alethia is my spiritual muse, you know?” says Cook. “I really feel a strong connection to her story because she had all the obstacles in her way.”

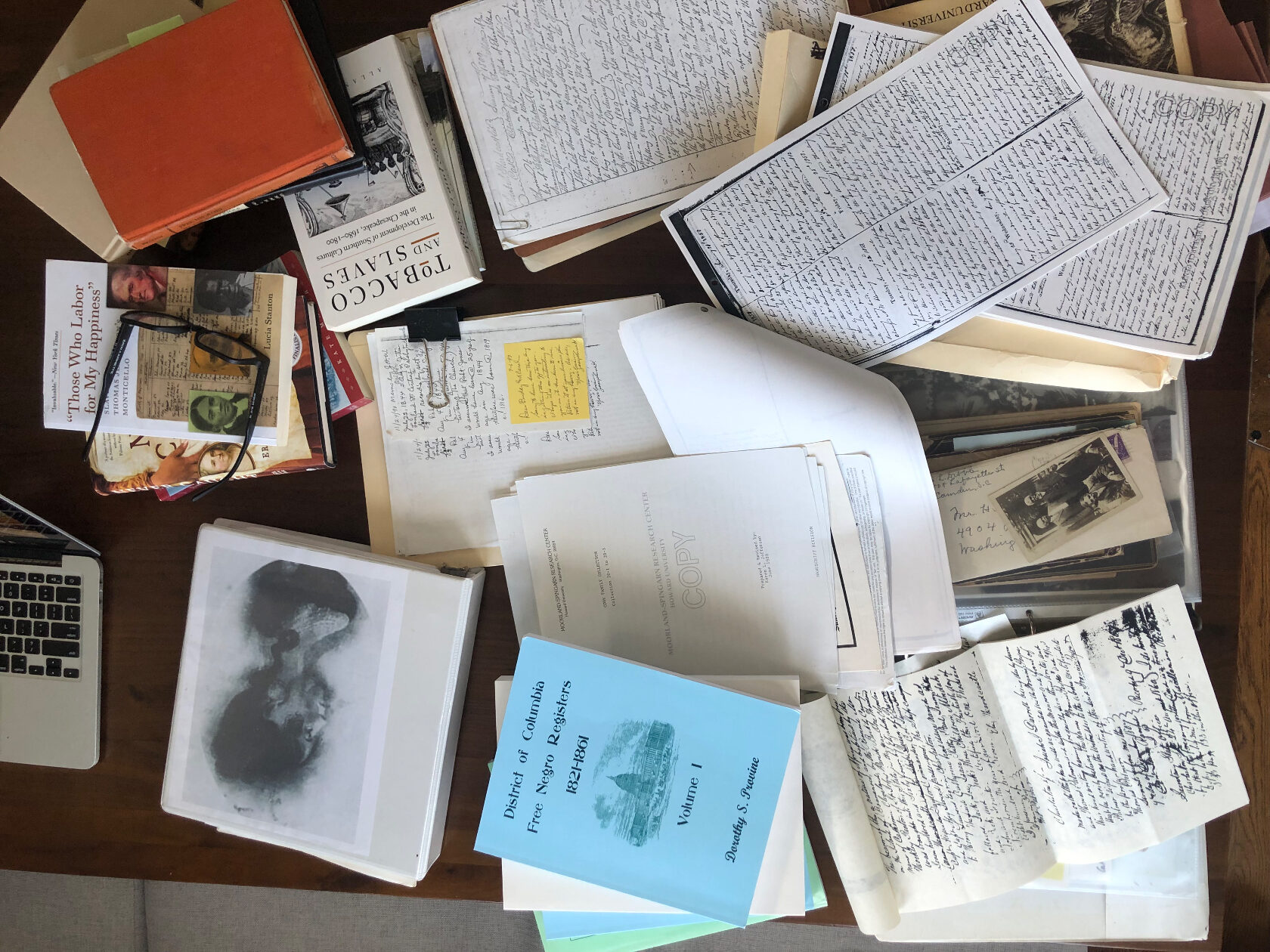

Since moving to D.C. with her partner a few years ago, Cook has spent some of her free time researching Tanner’s life. She’s worked with historians and has combed through primary documents, such as newspaper clippings and wills, to verify some of the stories she grew up hearing. According to Cook’s research, Tanner went on to purchase a property where her nephew opened a school and a church, which still exists today. Nearby, Tanner continued selling food for school children and other passersby.

“She had a legacy. She brought her family together. She united people,” says Cook.

Tanner was only nine years old at the time when D.C. was properly established in 1790. And Cook is adamant that Tanner was not the first or only Black street vendor in D.C. at the time. So she says it’s important to highlight the contributions of all the Black pioneers who helped shape D.C. into what it is today. Last July, the District celebrated the first ever Alethia Tanner Day during a ceremony at a park that was opened and named after her in 2020.

“Everyone has an Alethia,” says Cook. “I think… elevating stories like Alethia’s is elevating all these everyday people that we don’t know about but we’re really on their shoulders.”

Today, Tanner’s story has empowered others – including Black and immigrant street vendors throughout the District who have turned to her as a symbol for freedom and more than 200 years of Black street vending. When Sunni Stuart first heard about Alethia Tanner, she was speechless.

“Ancestors, they have definitely paved the way,” says Stuart, the co-owner of Sunni Teez Kitchen along with her husband, Shaun Stepney.

The duo opened their business in D.C. last summer. Taking inspiration from her grandmother’s cooking, Stuart offers crab cakes, mac and cheese, honey glazed salmon, and more. On most weekdays, the duo sell in front of the DC USA mall in Columbia Heights, which is a well known location for street vendors.

“It feels good to be a part of it because I’m doing something right,” says Stuart.

Business has been good for the pair, who recently sold out the day’s food after less than two hours of setting up their tent and chafing dishes. What’s more, they say they’ve even helped other chefs sell their own food. Stuart also says they provide nearby students with community service opportunities, or even just daily advice for the youth who want it.

“It’s so inspiring, so motivational, though, to just even experience this. It just brings hope for the community, honestly, in my opinion,” says Stuart.

Those experiences have motivated the duo to join up with other street vendors and their advocates to push for the D.C. Council to pass legislation that would decriminalize vending without a license, among other reforms.

“That’s why we’re fighting so hard to get these vendor laws changed because this is how we feed our family along with the other vendors,” says Stuart. “You know, we’re Black and it just feels good to just have positivity right out here in the streets.”

Felix Macaraeg says passing a bill to reform street vending would honor Tanner’s legacy by supporting today’s Black and immigrant vendors. Macaraeg is the organizing director for the Beloved Community Incubator, a local organization that has advocated for legislative reform on behalf of street vendors.

“I think vendors have always, in D.C., stood for freedom and self-determination and sharing your culture as a path to freedom for yourself and your family,” says Macaraeg. “Vendors today are following in the footsteps of that deep legacy.”

Last week, the D.C. Council approved a bill in its first reading and first vote that would not only accomplish decriminalization but also establish proper vending zones with a pilot program in Columbia Heights, where Stuart and many others operate. The legislation, known as the Street Vendor Advancement Amendment Act of 2023, is a combination of two prior bills that failed to make significant progress last year but was reintroduced this year by Ward 1 Councilmember Brianne K. Nadeau with the newfound support of D.C. Council Chairman Phil Mendelson.

“One of the things that makes me most proud about this bill is the way that it impacts people of color across the district,” Nadeau told WAMU/DCist. “In particular, people in Ward 1 who have been trying to become entrepreneurs and try to make a living doing things that they specialize in, that they’re good at, that utilize their skills, but have been hamstrung by the regulations that we have in place and a code that is just not welcoming.”

Although the bill requires a second council vote and approval before it can move on to Mayor Muriel Bowser’s desk, this legislation is some of the closest that relief has come for street vendors. In addition to decriminalization, it would waive any unpaid civil citations and significantly reduce the cost of basic vending licenses to $99, which could be renewed every two years. The cost for new sidewalk vending permits would also decrease to about $75.

“We living with hope, you know?” says Kahssay Gebrebhran, an Ethiopian street vendor who first started selling hot dogs and half-smokes in 1990.

Gebrebhran says that because of the initial covid outbreak in 2020, he allowed his vending license to expire because he didn’t feel safe going out to his regular location near the D.C. Superior Court on Indiana Avenue. According to Gebrebrehan, he currently owes more than $3,000 for failing to pay quarterly sales taxes during that time. As a result of D.C.’s Clean Hand Certificate, which requires applicants to show they don’t owe more than $100 in fees, fines or taxes to the District, Gebrebhran can’t renew his license. He hasn’t worked since.

“I miss my customer and they miss me also [but] I don’t have choice. What can I do? Without license I cannot work,” says Gebrebhran.

According to the bill’s text, the money that Gebrebhran owes would be waived if the bill were to eventually make its way into law. For Macaraeg, that reform is long overdue for Gebrebhran and many of the city’s Black and immigrant street vendors. Last year, the Beloved Community Incubator published a report which analyzed street vending arrest data from the D.C. Sentencing Commission. It found that over 95% of those arrested between January 1 of 2018 and September 30 of 2022 identified as Black, Indigenous, or People of Color.

“They’ve been enduring humiliation and hardship and criminalization for their beautiful work for decades before I ever met them,” says Macaraeg. “There have been waves of vendors trying to struggle for their rights. And I think this is going to be one of the most substantive reforms the city has seen in over 100 years. How can we not be thrilled? And this whole thing has been led by a very diverse group of Black D.C-ans and migrants from all over the world.”

Teresa Goodwin, also known as “Ma Teresa,” says an overhaul of D.C.’s current street vending laws would not only make it easier to run her business but is also a step toward justice for numerous families and individuals just trying to make a living. She says street vendors have long been criminalized and misunderstood but that it’s time to change the narrative.

“We deserve a chance,” says Goodwin, who owns SmokenMunch DC with her son.

Goodwin started the business in 2019 at her son’s suggestion. Since then, they’ve been serving the community in Anacostia and throughout D.C. with what she calls Southern comfort food with a twist, like Caribbean-cuisine and vegan dishes. She says her business has allowed her to share her love of cooking, a tradition that was passed onto her, with the community.

“When I leave this world, there’s only one thing I’m working so hard for, now, is to be able to say, ‘I made a change.’ That’s it. ‘I made a change with my cooking,’” says Goodwin.

For Chuck Bradley, a change to D.C.’s current street vending laws would mean getting a fair shot at a second chance. Bradley is a Black street vendor who sells things like socks, shoes, t-shirts, and jackets. He recently came home after being formerly incarcerated but it didn’t take long for him to get involved in the fight to overhaul the District’s vending laws.

“I get to be a part of a beautiful organization that’s about building wealth for the community and building love and respect for each other,” says Bradley. “It feels good to be on the right side.”

Like other vendors, Bradley says he’s had his own experiences of negative interactions with law enforcement and being accused of selling stolen goods. He also says he’s had people try to steal his items or try to run him off the block. Still, that hasn’t stopped him from trying to make-ends-meet on his own terms.

“My stuff is not stolen or anything. I purchased this stuff for myself, you know. And I’m trying to make me an honest living by changing my lifestyle and my way of my thinking,” says Bradley.

Bradley says his deep sense of faith has allowed him to not only support himself by vending but also to help others in need. Whether it’s a young person who needs guidance, other street vendors, or just someone in need of clothes to keep them warm, he says he will always find a way to support the community.

“I know the struggle is real,” says Bradley. “So what I give away is materialistic, but what God give me back in return is a blessing.”

While Cook says she wasn’t initially familiar with the street vendors and their connection to Tanner’s story, she says she’s happy that her ancestor, along with those like her, have not been forgotten by the community.

“I mean, it’s wonderful that they point to her because I think she is inspiration for so many ways,” says Cook. “There’s totally a correlation between Alethia and today’s street vendors.”

Héctor Alejandro Arzate

Héctor Alejandro Arzate