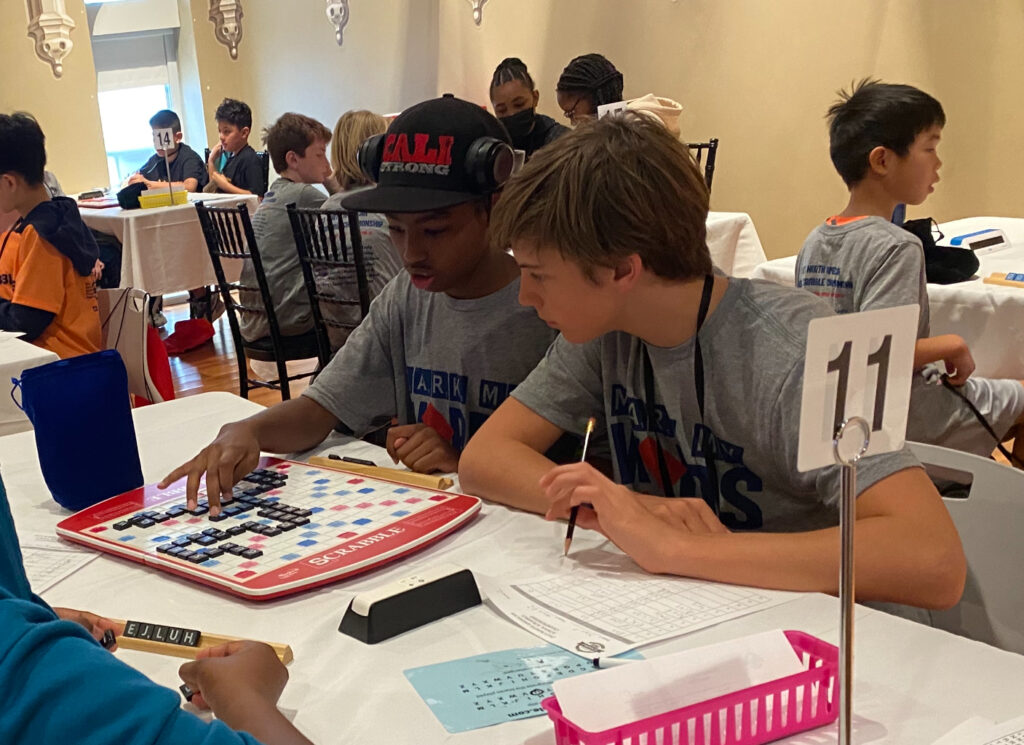

The sound of clanging letter tiles filled the air at the North American School Scrabble Championship at D.C.’s Planet Word Museum last weekend. Dozens of games of Scrabble were underway as players pulled omnipresent “A” s and dreaded “Q” s out of velvet bags.

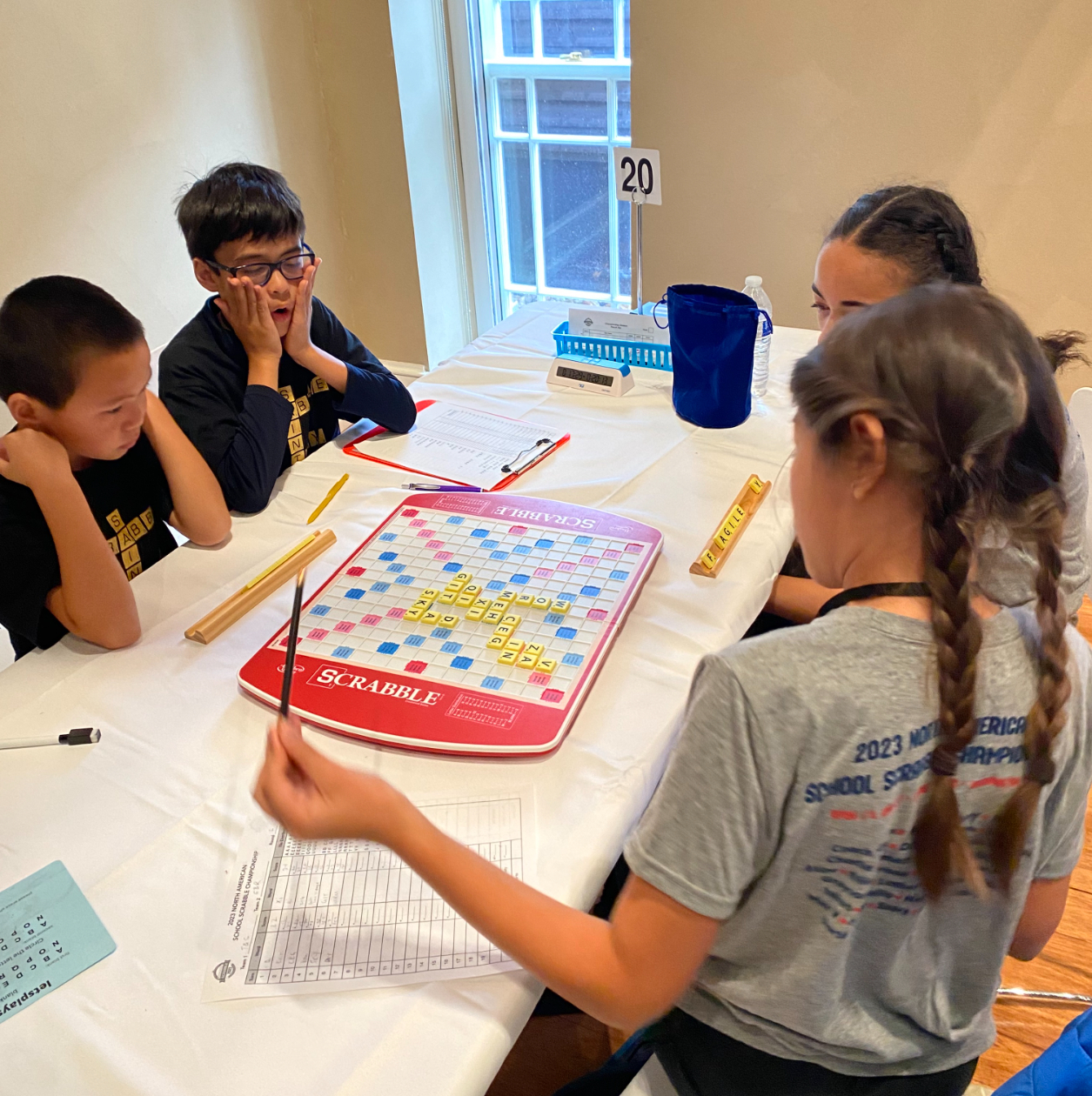

There were about 110 young players in the room on the fourth floor of this museum dedicated to words. The competitors ranged from 8 to 18 years old. Winners got up to $1,000 in cash, plus a fancy new Scrabble board.

They came from across the continent to the local museum to participate in the weekend-long tournament playing one of the world’s most popular board games. Some traveled from as far away as Canada, while others only had to come a few miles. Thirty-five players were from the District, including a number who attend Alice Deal Middle School in Northwest.

What these students all had in common, though, was their love for and skill at playing Scrabble.

Turns were taken and letter tiles were placed on the board, spelling words like worm, intel, and cooee.

“That’s my favorite vowel dump,” Alice Deal sixth grader Julian Riggs told DCist/WAMU about cooee, defined as a cry to attract attention, moments before the games began. “A vowel dump…. is just a word with two or more vowels.”

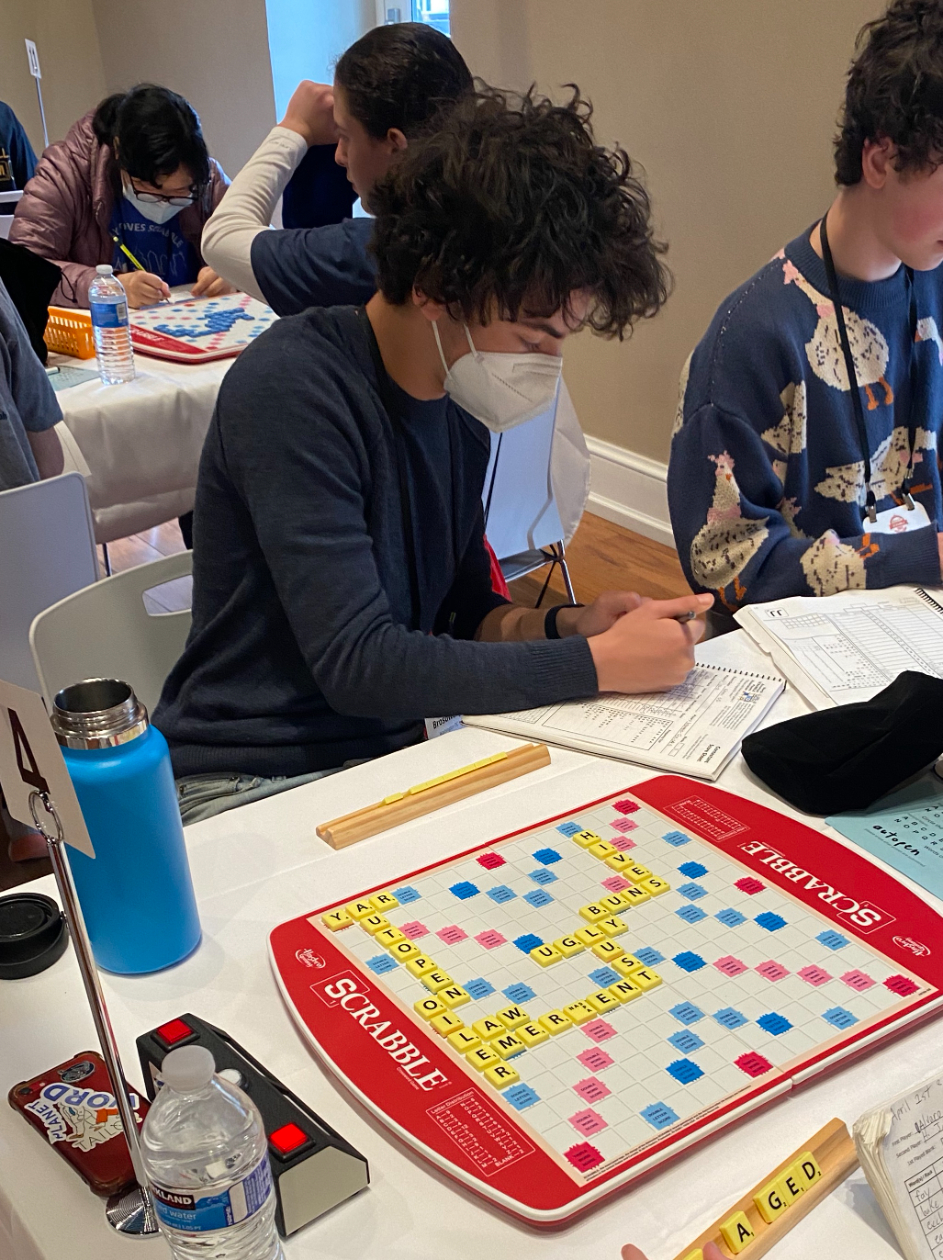

“Every single turn is like a new puzzle,” Emmett Brosowsky said. He’s a senior at the School Without Walls in Northwest and ended up finishing eighth in the high school division. “You have to consider the psychology of your opponent…you have to have word knowledge, what plays are possible. You have to have the finding ability to see the spots on the board. It’s just a very satisfying puzzle to solve.”

The North American School Scrabble Championship has been going on for about two decades, but it is the second year of it taking place at the Planet Word Museum in Northwest D.C.

The tournament pits elementary, middle, and high school students from across the continent against one another in a series of Scrabble games, all lasting 50 minutes. The younger students are paired up on teams of two while the high school students play each game individually.

D.C.-resident Stefan Fatsis has run the tournament since 2020. That name may sound familiar to Scrabble enthusiasts. He’s the author of 2001’s “Word Freak,” the New York Times best-seller that took readers into the world of competitive Scrabble Players. He’s also a ranked player and a long-time coach, teaching young scrabblers at Alice Deal Middle School.

“Scrabble is a game of risk and reward. It’s a game of high moments… ‘Oh my God, eureka!’ with the kids especially,” Fatsis said. “And it’s a game of lows. Like, ‘Oh no, I’ve got a rack of four ‘I’s, two ‘U’s, and a ‘Z.’ What do I do?'”

Fatsis explains that a big part of his coaching is helping kids learn the basics and terminology of the game, like internalizing all 107 accepted two-letter words, knowing what a “bingo” is, and always looking for prefixes and suffixes.

He said he loves coaching kids because they have “plastic brains” and are built to “inhale words.” This allows them to absorb and process at a much higher rate than adults all the tricks and strategies that turn a living room player into one competing at tournaments.

Another thing Fatsis teaches is that the game isn’t all about words.

“The dirty little secret of Scrabble is that it’s not a word game,” he said. “It’s a math game. It’s about probability. It’s about spatial relations; it’s about geometry; it’s about strategy. It’s about equity. At the highest level, it’s sophisticated math thinking.”

For many kids at the tournament, it remained all about the words. Alice Deal 8th grader Luther Kiyvyra said he started playing Scrabble at the age of seven because of refrigerator magnets.

“I used to make words a lot with, like, anything in the house. I love fridge magnets,” he said. “I would just find words around the house, and I’d be like, ‘oh my goodness, it’s a word.’ It would just boggle me how many different words there were around the house. And then I found out there was a game where you can put them on a board and score points and win.”

Kiyvrya said that playing Scrabble has helped him with his decision-making and problem-solving skills. It also has helped him learn that everyone learns differently, including himself.

“I’ve never been good at spelling tests, but I’ve learned to recognize words when I see them,” Kiyvrya said.

Kiyvrya, along with his partner Max Van Leeuwen, ended up finishing sixth in their division.

Before joining the Scrabble club, Rory Felton had only played the game once.

“I played it [on a team] with my grandma, and she was cheating,” said the 6th grader. “And we still lost.”

But playing Scrabble has helped Felton learn a lot of new words, even some “weird” ones like zyzzyva, a tropical weevil, or aarrghh.

“When you are mad, you say ‘argh.’ When you are really mad, you say ‘arghh.’ And when you are really, really mad, you say ‘aarrghh,” Felton said, laughing.

Several students said they could not care less if they won or lost at the weekend Scrabble tournament. They were there to have fun, hang out with friends, and learn fun words.

Fatsis said that’s precisely what he wished for. He wants the kids to get joy out of playing the game, much like he does, while continuing to embrace it into adulthood.

“It’s a life pursuit. Every word you learn makes you a better player. Every game you play makes you understand strategy a little better,” he said. “So it doesn’t have to be this obsessive pursuit. It can be this more steady marathon, not a sprint.”

Students like Emmett Brosowsky, Luther Kiyvyra, and Rory Felton all made it clear that for them, Scrabble isn’t simply a board game. It’s a way to discover new words, solve puzzles, and figure out how they learn best.

“It sounds crazy that a board game could change your life,” said Fatsis.”But it changed mine.“

This story was updated to correct the spelling of a player’s last name, the year that Stefan Fatsis began running the tournament, and “Q” being a dreaded letter as opposed to “Z”.

Matt Blitz

Matt Blitz