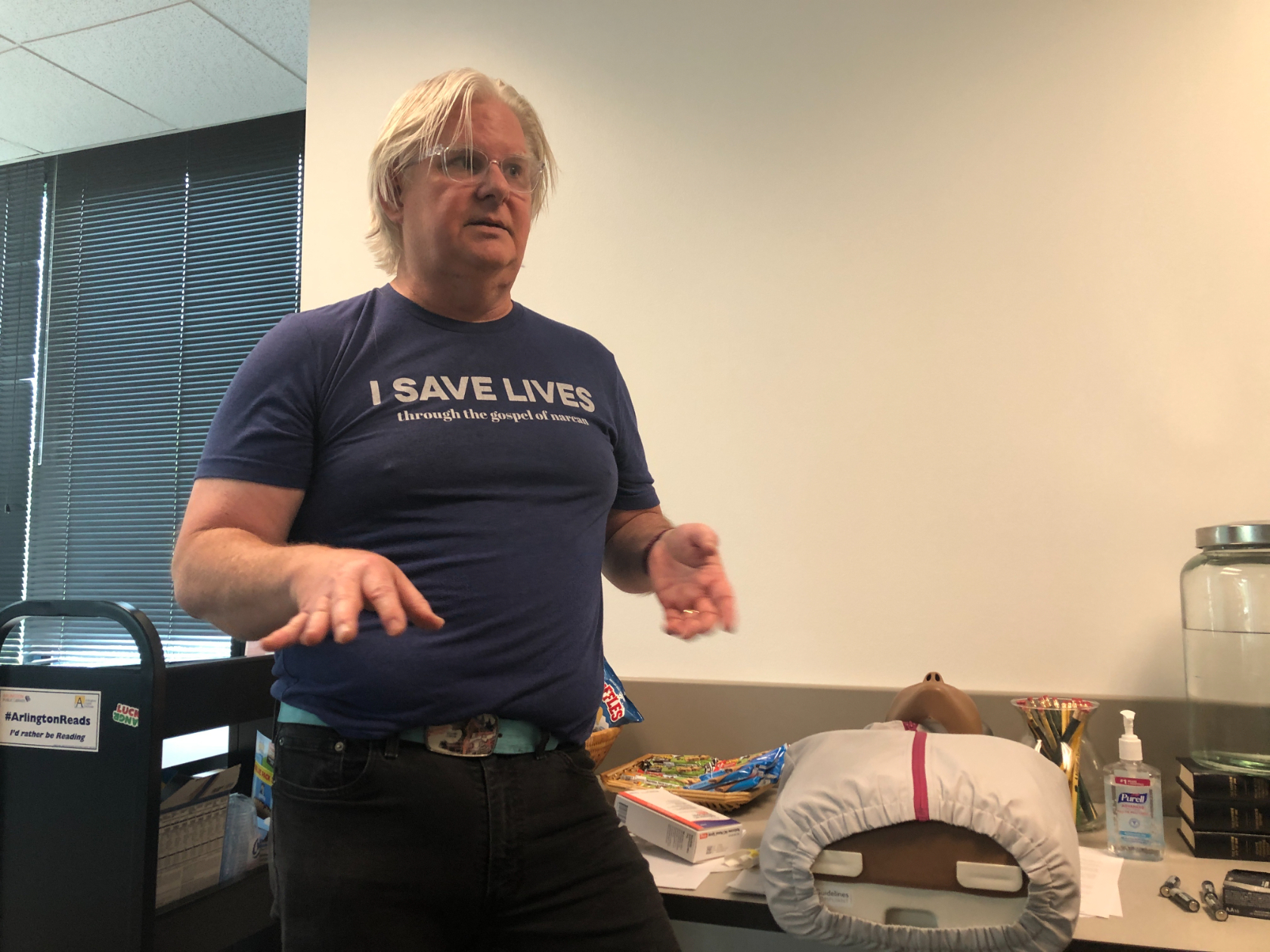

In a small room on the second floor of Arlington’s Central Library, high school students stand over a CPR manikin on a table. The manikin is surrounded by snacks, a cup of pencils, and boxes of Narcan.

Narcan trainer Jim Dooley inserts the naloxone nasal spray into the manikin’s nose. He’s showing students what to do if they find someone unresponsive at school. It’s not always clear if someone unresponsive is experiencing an opioid overdose but he says that they should call 911 and administer Narcan regardless. It is not a substitute for medical care but it can quickly prevent an overdose from becoming fatal.

“The only thing that Narcan does,” he says repeatedly, “is physically knock those opioids off. And that allows them to spontaneously breathe again. That’s it. There are no side effects.”

It’s a point he and his co-trainer, Emily Siqveland stress over and over.

“You will not cause harm by administering this when it’s not needed,” Siqveland says to students. “Keep that in mind, that’s by far the most important thing I want you to take out of this conversation.”

As opioid overdoses among youth continue to rise locally and across the country, Arlington County and its school district has been taking measures to make Narcan more accessible. Most recently, Arlington Public Schools introduced a new policy that allows students to carry their own Narcan, provided that they attend one of these training sessions and get parental consent. The policy went into effect late May.

Some of the training sessions can take an hour. But others, like the one at the library, are drop-in sessions. Each student can come whenever they want within an hour-long slot and can get trained in as little as 10 minutes.

High school student Pablo Swisher-Gomez says the library training was “quick, easy, and informative.” He decided to come after learning about the session from his father. He says he wants to keep his peers safe.

“You never know when something could happen,” he says.

Swisher-Gomez attends Wakefield High School. One of his schoolmates died from an apparent overdose earlier this year. The student was 14 years old.

Darrell Sampson, executive director of student services for APS, says the new Narcan policy drew strong support from parents, and that many of them continuously pushed for the measure over the spring.

“That loss of that student was felt from all parts of this county,” Sampson says.

Sampson adds that the opioid crisis seems to have come “closer to home” in Arlington this year, with more students seeking out resources for addiction and substance use. Both fatal and non-fatal opioid overdoses countywide have been up since the pandemic began. Nationally, overdose deaths among 14 to 18 year olds went up by 94% from 2019 to 2020, according to the CDC.

This ongoing surge and FDA approval of Narcan’s over-the-counter use have prompted more schools in the D.C. region to allow students to carry the nasal spray. Arlington was among the first, and school districts in Fairfax County, Alexandria, Montgomery, and Prince George’s Counties have similar policies. DC Public Schools hasn’t issued a policy explicitly allowing students to carry their own Narcan, but it has required that all schools in the District make it available. (D.C. residents can get Narcan in any ward for free with no ID or prescription.)

Swisher-Gomez says teenagers who use drugs are often struggling with their mental health.

“I’m not gonna lie, COVID definitely made things worse for a lot of people,” he says. “The mental health stuff is real. People are more open about that now, which I’m glad – but it’s definitely still a struggle that people don’t necessarily always talk about.”

He wants resources like therapy to be more accessible for young people. Swisher-Gomez says he was able to focus on improving his mental health through residential treatment. It was “really helpful” but “super expensive.”

“That’s just a really big problem,” he says. “A lot of people end up not getting the help they need.”

Nearly half of Virginians who need mental health care do not get it because of the cost, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

Gloria Fosso, a student at Washington Liberty High School, says there is more awareness now around youth mental health. But like Swisher-Gomez, she feels resources still aren’t as accessible as they should be.

“We do get a lot more help,” she says. “I would say that the help isn’t coming at the rate of students needing the help. More and more students are getting more and more depressed.”

Fosso says a lot of her peers use drugs to cope. She says school is “hella – excuse my language – very stressful,” and that quarantine took a toll on students with difficult home environments.

“I would say the pandemic made a lot of things worse,” Fosso says. “It might be that, or I’m just noticing it more as I get older.”

She says more parents need to think of drug use as a mental health issue, rather than a crime.

“Parents are very judgmental,” she says. “There’s also a very negative stigma around addiction.”

Fosso says that could probably be isolating, and that some students have moved out of Arlington because of the rise in overdoses. Their parents are fearful of the area. Some tell their children to avoid going near Wakefield High.

Still, Fosso’s optimistic that parents in the county will embrace the new Narcan policy because they want their children to be safe and keep others safe.

Emily Siqveland, who is also opioids program manager for Arlington’s Department of Human Services, says the county is “lucky” that parents have been very supportive of the policy.

“I think it also allows students to feel very empowered and to recognize how safe and effective this medication is,” Siqveland says. “This policy is one of those ways to communicate that.”

That kind of acceptance from parents isn’t universal. Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, says some school districts aren’t making Narcan accessible because of a mistaken belief that it condones substance use.

But Volkow says letting students carry and administer it is a “no-brainer.”

“The reality is that if you lose someone, all of your logic, all of your arguments are no longer valid. I mean, the person died. There’s nothing else that can be done,” Volkow says.

She added that teenagers who aren’t seeking out opioids can still accidentally overdose after taking counterfeit pills. For example, a pill made to look like Adderall, a common study drug, could be laced with fentanyl. Volkow says the spread of fentanyl is one of two major factors driving up overdose rates in recent years. The other is the pandemic, which exacerbated mental health issues in young people.

Letting students carry Narcan is just one of several measures APS is taking to mitigate the opioid crisis locally. Darrell Sampson says they expanded substance use classes to fourth graders this year, where students learn about opioids, alcohol, and prescription drugs. It was just last year that they expanded it to fifth graders. Students are also taught what to do if their peers are struggling with their mental health or expressing suicidal thoughts.

In the coming school year, Sampson says APS is planning to bring in more substance use counselors, as well as intervention counselors to help students dealing with anxiety or stress. They’ll also be making clinicians from the county’s Department of Human Services available for students who might need therapeutic intervention.

“This isn’t simply a schools’ issue,” Sampson says. “It is truly, truly a community challenge that all of us together must work to face.”

As difficult as the school year has been, Swisher-Gomez is hopeful things that things are going in a positive direction. There are more local mental health resources, and his peers have become more open to asking for help.

“To anyone out there, you’re not alone,” he says. “If you do need help, try your best to talk to a professional. But the main thing is, you’re not alone and you can get through it.”

Sarah Y. Kim

Sarah Y. Kim