After an unusually dry spring and early summer, thunderstorms finally rolled into the D.C. area in early July, filling up creeks and rivers, and overwhelming sewage systems. Parched lawns and gardens bounced back, and everyone’s least-favorite sign of summer — the mosquito — was again thriving.

So, is the drought in the region over? Yes and no.

In terms of drinking water, the D.C. area is now in good shape, says Mike Nardolilli, executive director of the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin, which tracks water supply in the area.

“We were really in a very dry period, and we were concerned because the dry period had occurred so early and in the spring when it’s usually very wet,” Nardolilli says.

In June, the commission began conducting daily drought monitoring, the first step when there’s concern that water demand could outstrip water supply. It was triggered by low flow levels on the Potomac River, which provides most of the region’s tap water. But drought monitoring only lasted about a week. Now, daily water flow on the Potomac is at about the same level as last year, and roughly equal to the 128-year median.

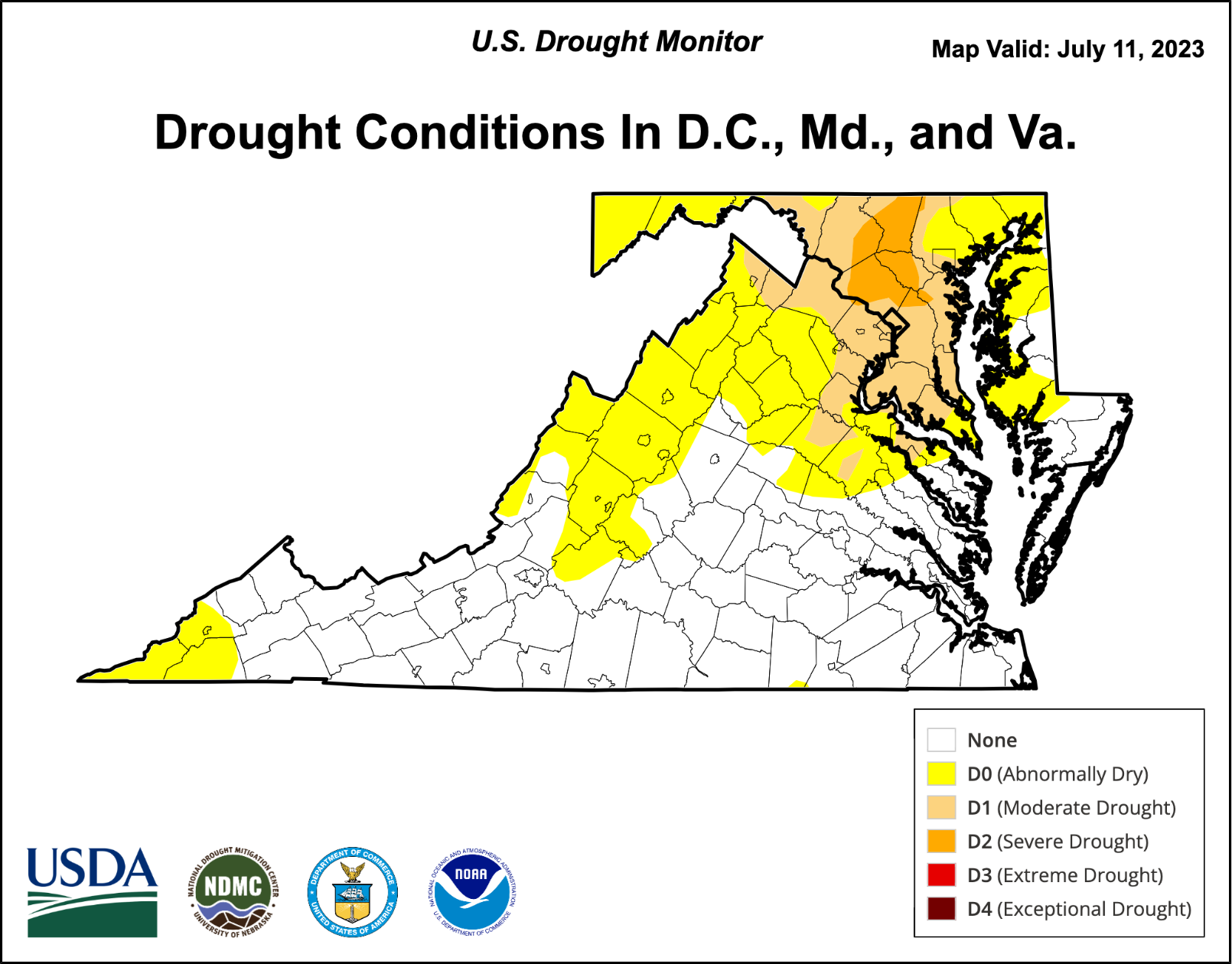

However, the latest data from the U.S. Drought Monitor, released this morning, shows the region is still experiencing drought conditions. Most of Northern Virginia, including Arlington County, Fairfax County, and Loudoun county are in a moderate drought, as is the District. In Maryland, parts of Montgomery County, Prince George’s County, Howard County, and Anne Arundel County are still in severe drought — the only places on the East Coast in that category, except for a handful of counties in Florida.

In the Potomac River basin, rainfall totals are still well below normal. Year-to-date, the watershed has had 5.8 inches less rain than usual. That can be an issue especially in places that rely on groundwater, as underground wells recharge much more slowly than surface reservoirs or rivers.

Maryland recently issued a drought watch advisory for the northern part of Montgomery County and central and western portions of the state, areas that depend on groundwater. The drought watch asks residents to voluntarily conserve water.

“You can do your part by limiting the use and duration of sprinklers for lawns, taking short showers as opposed to baths, and not leaving the faucet running while brushing your teeth,” said Serena McIlwain, Maryland’s secretary of the environment, in a statement.

In the D.C. area, there’s a drought plan that has been in place since 2000, when the last major drought occurred. Since then, it’s never been fully activated, says Steve Bieber, water resources program director at the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments.

COG has only ever issued a drought watch — the first stage in the plan. That has occurred three times since 2000. After a drought watch, COG could move to the next level, a drought warning, if upstream backup reservoirs drop bellow 60% capacity for five consecutive days. Those reservoirs are currently at 100% capacity, Bieber says.

“The region invested back in the early ’80s in upstream reservoirs for drought resilience,” Bieber says. The reservoirs are designed to provide enough water even in very dry conditions, like those experience in the worst drought on record in the region, which occurred in the 1930s.

The next stage after a drought warning would be a drought emergency, which is triggered when there is a 50% or more probability that water supply doesn’t meet water demand in the region.

Nardolilli says that while recent rainfall has improved the water supply outlook, the region could still get another dry spell this summer or fall.

“Because the early part of the year was so dry, we’re not making any bets,” Nardolilli says.

Jacob Fenston

Jacob Fenston