As soon as COVID-19 vaccines were available, Maryland resident Cynthia Cox knew she wanted one — especially before her risk of infection increased on her upcoming cross-country flight to attend a conference in California. Cox researches health insurance for a living, so she knew that the end of federally-provided COVID vaccines meant she’d have to be careful to find somewhere in her insurer’s network that also had available doses. But Cox hit snag after snag in her search for a covered, local vaccine, ultimately hopping in the car for an hour-long drive to Frederick, Maryland, to get her booster in time for her trip.

“I work in health insurance policy, and yet it was the health insurance bureaucracy that kept me from getting the vaccine,” says Cox, who is Vice President and Director at health policy research organization KFF who focuses on the Affordable Care Act.

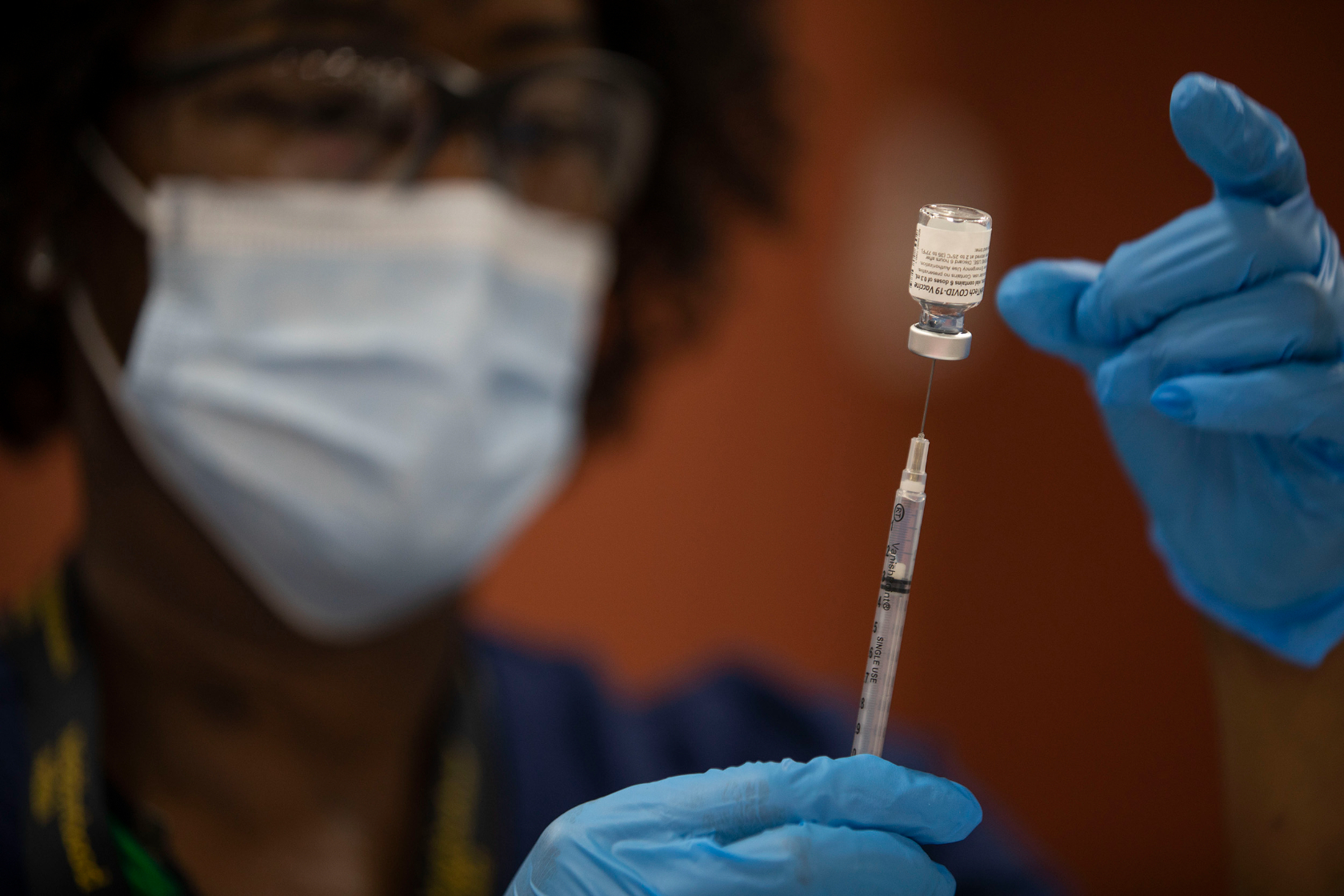

On September 12th, the CDC recommended the updated FDA-approved COVID vaccine for patients 6 months and older. But the federal government is no longer buying and distributing vaccines, putting private insurers on the hook to cover the $115 to $128 per dose that Pfizer and Moderna are now charging.

While patients were able to start scheduling appointments weeks ago, many have reported cancellations and struggles with insurance. Experts are particularly concerned about the barriers faced by those who already have limited healthcare access.

“Our hope is that the slow start when it comes to receiving vaccines improves over the next few days and weeks,” said Basim Khan, the CEO and primary physician at Neighborhood Health in Virginia. “We are hopeful that will be the case so that we can vaccinate our low income patient population — both those who have insurance and those who are uninsured.”

While COVID-19 numbers are still below what they were around this time last year, weekly CDC data shows an uptick in hospitalization, spurring many to want to get vaccinated as soon as possible.

Senior Vice President at KFF, Jen Kates, also initially struggled to get vaccinated — especially before a scheduled visit with her older parents. Her late September appointment at a D.C. pharmacy was canceled without explanation. She reached out to her local CVS and Walgreens to try and understand what was going wrong.

But she says she didn’t get much information from an apologetic pharmacist who told her: ‘We’re really sorry. We don’t have any supply; we’re getting very few at a time yet the system is letting people schedule their appointments anyway, and so we keep having the appointments canceled.” The Walgreens store had a similar response, she said, and were uncertain when things would change. They were also out of flu vaccines at the time.

A CVS spokesperson told DCist/WAMU: “We’re receiving updated COVID-19 vaccines from suppliers on a rolling basis and most of our locations can honor scheduled appointments. However, due to delivery delays from our wholesalers, some appointments may be rescheduled. We apologize for any inconvenience this may cause.”

Why is this happening?

Initial issues stem from the fact that many private insurers didn’t have the medical billing codes for the new vaccines, which are used to identify the cost of diagnoses and procedures. While Kates says some pharmacies still haven’t gotten their systems ready to communicate with payers, appointment cancellations and delays are now more likely to be due to supply chain issues.

“There seems to be a bottleneck or some kind of challenge between getting that vaccine from the manufacturers to the delivery sites,” she says.

It’s unclear exactly why this is the case, she adds, since sufficient vaccines are being produced to meet demand — unlike with previous rounds of COVID-19 vaccines.

These kinds of supply issues can be quickly exacerbated by the complications of a privatized system, where insurance coverage can vary from site to site.

How will this affect low-income and uninsured patients?

Some observers worry that the vaccine rollout will be complicated by the ongoing Medicaid unwinding, which is causing thousands of eligible patients to lose their health insurance in the region.

“This isn’t happening in a vacuum,” Kates says. “It’s happening in the wake of the ending of the [Public Health Emergency] declaration, the unwinding of continuous enrollment in Medicaid, the ending of several other protections and safeguards that were put in place during the COVID emergency.”

There are options for uninsured patients to get vaccinated through the CDC’s Bridge Access Program, which assists adults without insurance through the end of 2024, and Vaccines for Children – a federally funded program that provides vaccines at no cost to children at participating practices.

Federally qualified health centers, a vital source of healthcare for uninsured and low-income patients, are also facing vaccine delays. Khan says it may be days or weeks before vaccines are available at all for their patients.

“Even when we do receive a supply, it’s going to be much more limited than it has been with previous rounds,” Khan says.

What if the government threatens to shut down again?

The federal shutdown has been avoided – at least until Thanksgiving. But if the government were to shut down in the future, most COVID-related activities should be able to continue.

Still, a shutdown could impact staffing levels, with a spokesperson from Unity Health telling WAMU/DCist: “Our top priority remains being able to take care of our patients, and we remain concerned that any shutdown will have a negative impact on the livelihoods of those we serve.”

How much longer will these availability issues last? And what about vaccines for kids?

Cox says she’s hopeful that this period won’t last too much longer, and that by mid to late October vaccines will be more available. She worries, however, that parents seeking vaccines for infants and toddlers might see longer delays.

Although the FDA has approved the new vaccine for children 6 months and older, parents around the region may find it difficult to find a provider to vaccinate children from 6 months to 4 years old. According to the PREP Act, pharmacists can only vaccinate children who are three years or older. CVS Minute Clinics allow vaccinations for children as young as 18 months.

But parents rely primarily on pediatricians who may or may not have sufficient supplies, and have to balance provision with the cost of unused vaccines. Kids under 4 years old are also advised to have the same brand of vaccine, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics, which has limited options for some parents.

What can locals do in the meantime?

For many patients, it may just be a matter of waiting a couple more weeks for stocks to increase at pharmacies and orders to come through at doctor’s offices. Vaccine-seekers can check for appointments at www.vaccines.gov/ and see where there may be vaccine deserts in the region.

“The trouble with access can cause more trouble with access,” Cox says. “I think these access issues could cause providers to order fewer doses, and then we’re in a situation where it’s not clear whether it’s just supply or demand problem.”

In the meantime, patients can still exercise the same safety precautions as before until they’re able to get vaccinated: masking in crowded areas, staying home when symptomatic, and testing frequently. Free tests are available to order through the federal government and local libraries and community centers offer free tests and masks.

Aja Drain

Aja Drain