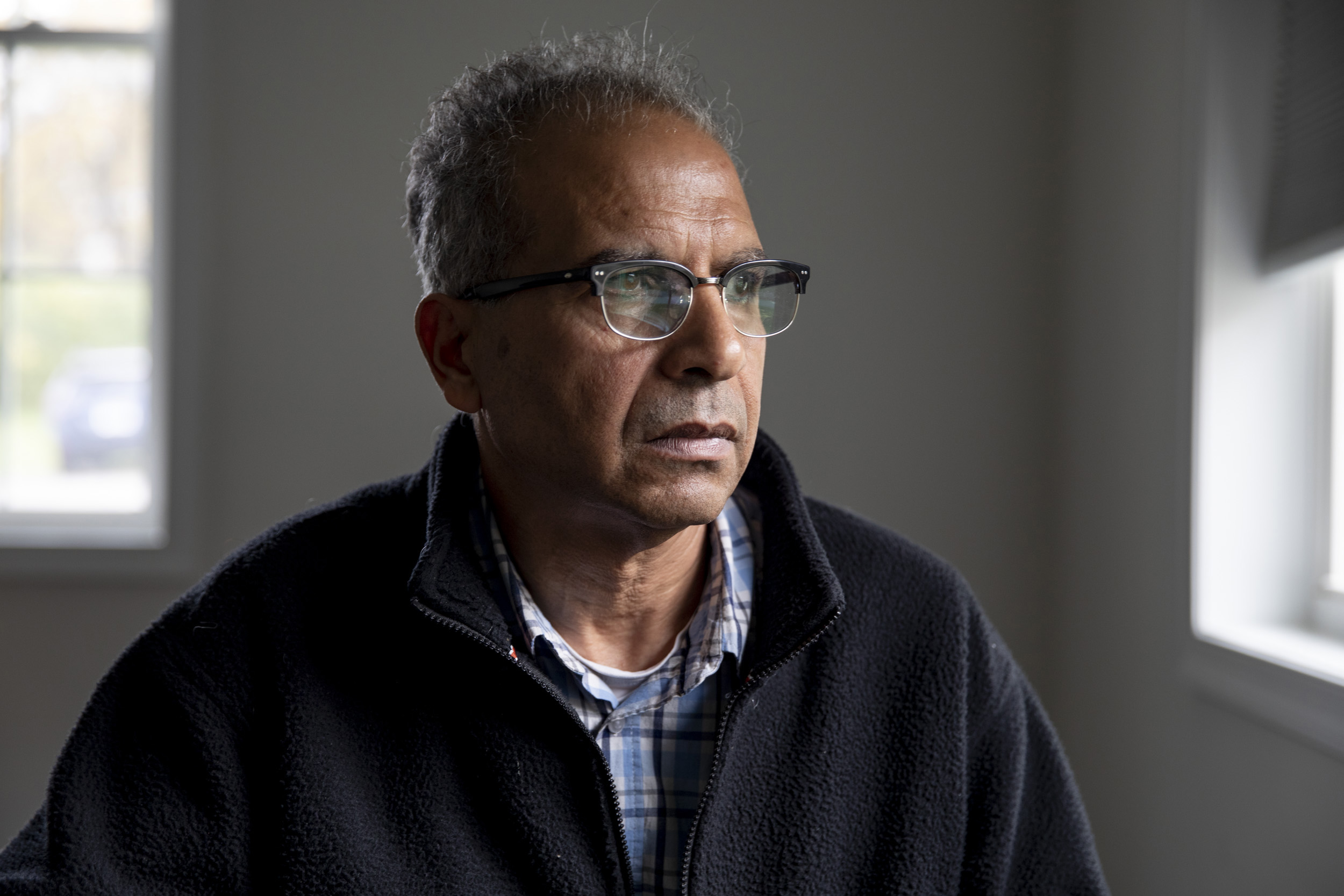

Adnan Sawada, a Palestinian American who lives in Gambrills, Maryland, was at work at his contracting business on Oct. 17 when he started to receive frantic WhatsApp messages from family. His brother, who lives in Gaza, asked “are you home?”

Initially, Sawada was confused; he thought maybe he received a message his brother meant for someone else. After a few minutes waiting for a reply, he decided he should just call to figure out what’s going on.

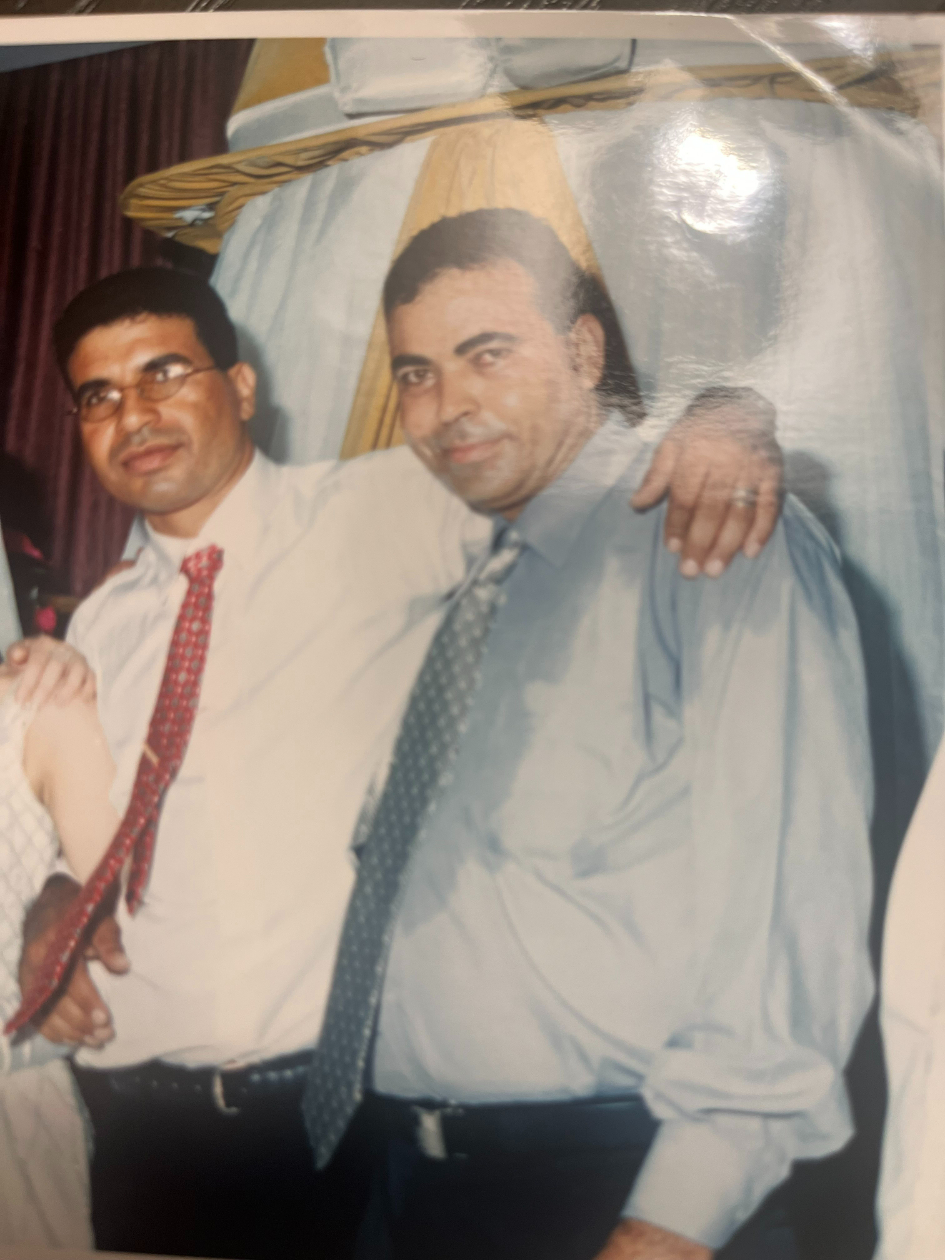

Over the phone, he learned his oldest brother, Shaaban — the “toughest person I knew,” eldest of 11, and accomplished electrician — was killed by an Israeli airstrike in Gaza.

“I was… angry. Hopelessness. Defeated. Unjust. Unfair,” Sawada says, trying to describe how he felt then, and how he still feels today as Israel’s attacks on Gaza, including intermittent communication blackouts, continue, and contact with his family remains constricted. “Many people asked me to describe it, but I really don’t know what the feeling looks like…I wish I could pull my heart out for you guys to see it.”

Sawada and fellow Maryland resident, Laila El-Haddad, are just two of hundreds of Palestinians with ties to Gaza living in the D.C. region; both of them had family members killed in Gaza over the past several weeks. Since Oct. 7, Israeli troops have killed more than 9,000 Palestinians — nearly half of them children — and maintained a siege on food, water, and power, following a Hamas attack in Israel that killed more than 1,000 people and took more than 200 hostage.

Now, Sawada and El-Haddad spend much of their days refreshing WhatsApp and checking texts, waiting on sporadic updates from their relatives. Because there is no electricity, messages can only come so often. Both say their families are often using something like a car battery — or really whatever power source they can find — to charge their phones and stay in touch.

“When I send them a message and they don’t reply for two days, or at maybe the end of the day or while I’m asleep or something, by the time I get back to them, they lost the internet,” Sawada says. “I want to know if they have enough money, I want to know, what did they eat?”

Sawada’s family — nearly 30 people — is currently staying in Rafah, in the south of Gaza near the Egyptian border. Months ago, he would talk on the phone with his relatives, particularly his brothers, once a week or so, swapping life updates as siblings do. Both he and one of his younger brothers had recently bought houses — Sawada in Maryland, his brother in Gaza.

Now, their missives are short and minced, just letting Sawada know that they’re okay without draining too much battery. In a recent update, Sawada learned his family in Rafah was sleeping in shifts; there was not enough room for everyone in their tent.

“I was told that some people — they boil water to drink it,” Sawada says. “I don’t know if they still buy water.”

Shaaban’s death came after several forced relocations, according to Sawada. Shaaban first moved his family to northern Gaza earlier in October, after an airstrike destroyed his apartment in central Gaza. Then, after Israeli officials told Palestinians in Gaza in the north (some 1.1 million people) to evacuate south in mid-October, the family moved to Deir al Balah, in central Gaza. In the phone call on Oct. 17, Sawada learned that’s where Israeli forces struck a building nearby as his brother stood outside. He was badly wounded, Sawada says, and taken to a hospital where he died waiting for treatment.

“My niece, my nephew said they were screaming at the doctors to save him,” Sawada says. “The hospital was really full, overwhelmed with injuries. My thinking is, he was older, maybe they were trying to save the babies first.”

Now, Sawada watches the news constantly and waits for his phone to ping in his pocket. He still shows up to work, physically — “it’s my bread and butter” — but in his mind, he’s elsewhere. He has attended rallies and protests in D.C., met with his local representative to demand a cease-fire, and leaned on his community of Palestinian Americans in the area — but he says even still, it cannot “take the anger and frustration out of your heart.”

“Every day I come to work, I want to go home. I want to bury myself sometimes,” he said. “But I guess if I’m feeling this way, I cannot imagine how they feel.”

El-Haddad lives not far from Sawada in Columbia, Maryland. She was born in Kuwait to Palestinian parents, and raised between Gaza and the Persian Gulf before moving to the U.S. for college. She went back to Gaza after finishing her studies, before ultimately settling in the U.S. with her family.

A former Gaza correspondent for Al Jazeera and three-time author (including one cookbook), El-Haddad has spent much of her life telling the human stories of ordinary life in Gaza — stories about food, and family, and pleasure. (She also showed Anthony Bourdain around Gaza City in 2013, clips of which have recently been going viral on social media.) Narrating these realities becomes a demonstration of resilience, she says, and a way of conveying to people in the D.C. region — or the West more broadly — how Palestinians have lived under a restrictive system of occupation.

“It’s a slow death by 1,000 cuts, and that doesn’t make the news,” she says.

Thinking back to her childhood, El-Haddad says she remembers the traumatic searches at border crossings (Israel controls all sea, air, and most land access to Gaza) — but joyful, sensory memories too, like swinging on a long, swooping branch of her grandfather’s centuries-old sycamore fig tree in Khan Yunis. She recalls getting a slushie in Gaza City with a dollop of Arabic ice cream on top, heading to the beach to challenge the waves, and catching crabs to cook with chilies and garlic over an open fire.

“These are the small joys that you miss,” El-Haddad says. “But I don’t know if any of that exists anymore.”

She’s lived in Maryland for 13 years with her husband and children, and her parents recently moved to Maryland from Gaza during the pandemic. But her uncles, aunts, and cousins are all still based in Gaza — primarily in Gaza City or in Khan Yunis. Her uncle, his children, their wives, and their children — about 25 people total — are living in one apartment in the city.

“They told me in a message over WhatsApp that they made the decision to die in the dignity of their own homes rather than risk another ethnic cleansing — what Palestinians refer to as the Nakba, which is what we experienced in 1948,” El-Haddad says, referencing the forceful expulsion of more than 700,000 Palestinians from their homes and the creation of the Israeli state in Palestine. (El-Haddad played the messages she has received from her family for DCist/WAMU.)

Most of her communications are limited to written messages and voice notes; the connection isn’t strong enough to support video calls. Through audio recordings, El-Haddad says her cousin relays how the family is doing; in one note, he describes how they huddled together on the ground floor of the apartment between two concrete walls during active shelling.

“It’s terrifying and disorienting all at once, and he’s trying to convey that reality to me in small little audio and voice notes,” she says.

“The first thing I do when I wake up in the morning is I just refresh my Whatsapp, and I quickly make sure to see what the last message they sent me was … and that’s the last thing I do before I go to sleep,” she says.

If she doesn’t hear back, she says she messages a group chat of Palestinian Americans from Gaza, asking if there’s been another attack or airstrike, or if anyone has heard from a certain family member. Then, they check the Palestinian Ministry of Health’s list of people killed — hoping not to see a loved one. When Israel completely severed phone, cellular, and internet services for nearly two days last weekend, El-Haddad says it was terrifying — “they were literally cut off from the world.”

“It’s emotionally exhausting,” El-Haddad says of the constant state of anxiety, not knowing from one hour to the next if another Israeli attack has killed loved ones. “I think, though, the most exhausting part of it all is having to explain over and over why we as Palestinians don’t deserve to be killed…why innocent civilians, why my family, why my uncle and my cousins, why they deserve to live with freedom, and with rights, and without bombs raining over their heads.”

El-Haddad’s fears materialized on Nov. 3, when she received news that her uncle’s wife, his wife’s oldest son, his wife, and their two adult daughters were killed.

As they manage keeping in touch with family and friends in Gaza, El-Haddad and Sawada have been connecting with their community locally — attending rallies and protests in the region and meeting with representatives in the region to demand a cease-fire.

Without knowing what each new minute holds, El-Haddad says she derives her hope from Palestinian people — including the dispatches she does get on her phone from her family. Her cousin’s daughter celebrated her 11th birthday on Oct. 14, and to mark the occasion, El-Haddad’s cousin made a cake with what they could find, providing a momentary distraction.

On her phone, El-Haddad received an image of her family members grinning around a table.

“Just those simple acts of joy, those mundane routine tasks become herculean acts of resistance,” she says.

Colleen Grablick

Colleen Grablick Tyrone Turner

Tyrone Turner Ayan Sheikh

Ayan Sheikh