This story was produced by El Tiempo Latino. La puedes leer en español aquí.

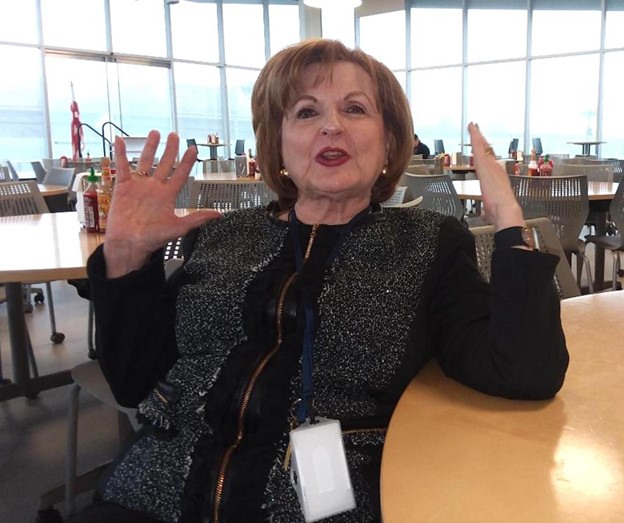

For over half a century, Sonia Gutiérrez, 84, has fought for the opportunities and rights of immigrants, setting an example of strength and resilience for new generations of Hispanic people.

When she retired from the Carlos Rosario International Public Charter School in 2019, she left knowing that the best part of her life remained there. “And you know what, dear? I did it with pleasure. I left two husbands over there, and I have no regrets,” she told El Tiempo Latino during a lengthy conversation embellished with anecdotes of times when Latinos were claiming their right to a place in D.C.

Her struggles for immigrants in the region, her legacy, and her example for Hispanic women are only comparable to that of one other local Latina: María Gómez, who founded Mary’s Center and made it a national model for health care, like the Carlos Rosario School is for education.

It was the early 70s and Gutiérrez quickly understood that there was much to do for immigrants in D.C. As a young mother and homemaker from a wealthy family in Puerto Rico, she met an indefatigable force named Carlos Rosario, who was also a Boricua. “The Old Man” and Gutierrez became a duo that would chase after everything – whether it was budgets for immigrant programs, grants to cover service costs, respect for rights, or the demand for citizenship.

So when Gutiérrez made it a reality to have a school for Latinos, where they could learn English and take the GED in Spanish, she didn’t hesitate to name it Carlos Rosario.

“It was The Old Man who started everything to provide immigrants with jobs, food, and services,” Gutiérrez says. “I was just the kid who followed in his footsteps, and that sticks, my dear.”

Much has changed from its beginnings as the Program of English Instruction for Latin Americans, with 100 students in a malodorous basement in Chinatown. Fifty years later, the school is synonymous with adult education. More than 2,000 students annually – 73% of whom are Latino – attend classes in two buildings, from which emanate nursing assistants and culinary arts professionals who work in the District.

“The greatest achievement is that everyone graduates with prearranged employment,” Gutierrez said with pride.

Fighting for the future

Over the years, if the threat of eliminating funds for the school or other Hispanic organizations reached Gutierrez’s ears, she would rally community members.

She remembers those moments with a subtle dose of mischief from someone who always got her way. When students heard her prayer, “Oh, Our Lady of Mt. Carmel!”, they would peer through the classroom door and ask “Where do we need to go protest, Miss Gutiérrez?”

One day, she took her faithful picketers to knock on the doors of an education superintendent when funding for the school was threatened. She said they didn’t lose a penny. “We even picketed the police because many were terrible to Latinos,” Gutierrez said.

Today, she would like to see the Hispanic community be more active in their demands.

“If I weren’t 84 years old, I would go to the border to fight for those who arrive. I wasn’t one to cry, but now, seeing how they mistreat those who come with nothing at all, I cry like a baby. Why don’t they understand that they come because they are starving in their countries?” she said. “Our misfortune was the election of Donald Trump; he is the most racist and anti-Latino thing that has happened to us. He has turned the Republican Party into a bunch of anti-immigrants.”

Many Carlos Rosarios (in plural, that’s how she sometimes refers to the students) show up unable to speak English and without jobs, according to Gutiérrez. They overcome, work two or three jobs, and find time to study. But Gutiérrez said no one recognizes that “Latinos only need a little push to fly.”

This comes from a woman who, between a brain operation, two knee surgeries, and gallbladder surgery, managed a school on Harvard Street and knocked on doors incessantly until she gathered more than $2 million to build her own building and open the school’s second location near the Rhode Island Ave Metro station. “If they tried to take away our building or failed to help us with the funds for the Harvard Street facility, we would have our own facilities,” she said of the expansion.

Her ex-husband, José Gutiérrez, who gave her the choice between the school and him, helped her get the last $250,000 needed for the new building. “Mind you, I adored that man, “ Gutiérrez said. “But I couldn’t accept him asking me to leave my students and stay home waiting for him with dinner in a nightgown. That’s not me.” To her, education and advocacy is a vocation.

Still helping students

Gutiérrez has an abundance of reputation, and she continues to use it. That’s how she filled the nearly three years of forced ostracism due to the pandemic. “I have the honor that no one says ‘no’ to me when I ask for my people,” she said. “When one of my former students calls me for a need, I make calls and ask.”

What she gets for all this legacy is summed up in a trip to a market earlier this year. Gutiérrez realized that a man was smiling at her as he approached. “Miss Sonia, I wanted to thank you. I studied English and got my GED at your school,” she recalls him saying. Chance encounters like this reaffirm to her that it was worth it.

To that constant drip of “thank you, Miss Gutiérrez,” she has a response: “Son, thank yourself for your efforts and perseverance.”

She listed many names of Latinos and Latinas who pitched in over the decades to ensure that they were recognized as a fundamental thread in D.C.’s social fabric. But speaking of the new generation, she mentioned with great affection Abel Núñez, executive director of CARECEN, and Jackie Reyes, director of the Mayor’s Office of Community Affairs. For all her students, Gutiérrez has one request: “never give up, don’t forget that Latinos are the future.”

This article was translated into English by El Tiempo Latino.

Olga Imbaquingo

Olga Imbaquingo