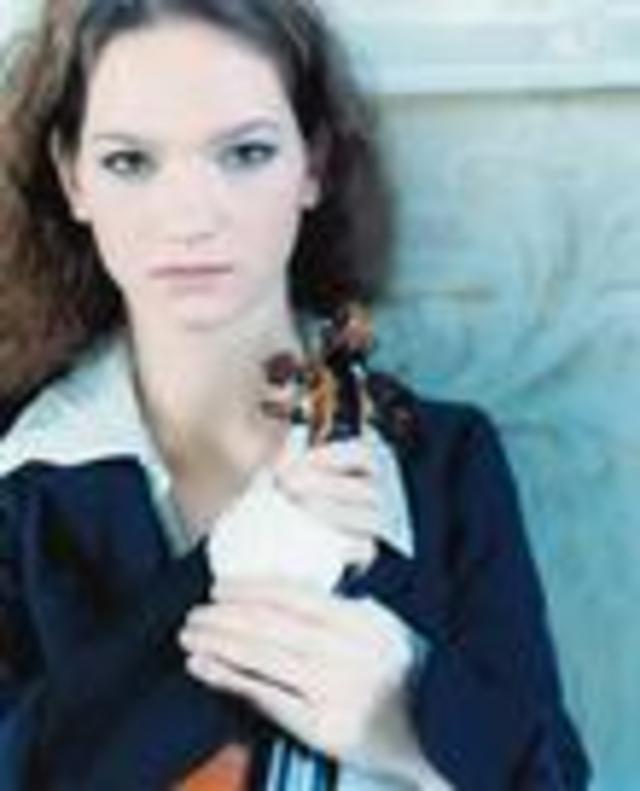

Hilary Hahn is 25 years old, from Baltimore, smart, pretty, and she maintains a Web site that is something like a blog. Oh, yes, and she is a world-famous violinist. Last night, DCist was there when she gave an excellent recital in the Kennedy Center‘s Concert Hall, with pianist Natalie Zhu. The program (.PDF file) combined some rare esoterica on the first half with more crowd-pleasing pieces on the second half. All of it was played beautifully and with the consummate musicianship, the perfect mixture of brio and brains that we have come to expect from Hilary Hahn.

Hilary Hahn is 25 years old, from Baltimore, smart, pretty, and she maintains a Web site that is something like a blog. Oh, yes, and she is a world-famous violinist. Last night, DCist was there when she gave an excellent recital in the Kennedy Center‘s Concert Hall, with pianist Natalie Zhu. The program (.PDF file) combined some rare esoterica on the first half with more crowd-pleasing pieces on the second half. All of it was played beautifully and with the consummate musicianship, the perfect mixture of brio and brains that we have come to expect from Hilary Hahn.

After a short delay following a gushing speech by Washington Performing Arts Society president Neale Perl, Hahn took the stage alone, in a strapless peach corset and iridiscent skirt. She opened with Eugène Ysaÿe’s first sonata for unaccompanied violin (op. 27, no. 1). Playing from memory, Hahn reeled off countless streams of flawless double- and triple-stops, difficult note combinations for the violinist to play on more than one string simultaneously. The first movement (Grave) was intensely introspective, rising from a hushed softness to Hahn’s characteristic soaring, bright tone. The second movement (Fugato) tries to imitate Bach’s fugal writing, for an instrument that is normally only called upon to play a single melodic line. We can add Ysaÿe’s name to the list of Romantic composers who admired fugue but could not actually reproduce the process themselves, beyond fairly simple contrapuntal interaction. The piece is a bear to perform, and Hahn’s rendition was technically stunning and musically inspired. We would have gladly listened to her play the other five Ysaÿe sonatas.

The highlight of the concert was Georges Enesco’s third sonata for violin and piano (A minor, op. 25), subtitled “On Popular Romanian Themes.” Pianist Natalie Zhu’s contribution was some of the most graceful, languid playing we have heard in a while, providing the landscape and costumes for the portrait of a Romanian gypsy fiddler that Enesco evokes. While always tasteful, Zhu’s playing was restrained, and in some of the most bombastic passages, we could have used perhaps a little more power at the keyboard. Although Enesco apparently never cites any actual Romanian folk melodies, the spirit and sounds of his native country’s folk music — the meandering parlando, the irregular meters, the pitch bends and blue notes of improvised playing — pervades this alternately earthy and ethereal sonata. As defenders of modern music, we were particularly pleased to see that this piece, composed in 1926, received the longest ovation of the evening. Perhaps we can expect an all-Enesco recording in the future?