A scan of a copy of the Washington Post from November 28, 1981

A scan of a copy of the Washington Post from November 28, 1981

Four months ago today, what is now known as the Occupy D.C. encampment in McPherson Square was born.

An offshoot of the larger Occupy Wall Street movement, the camp and the protesters that sustain it have ebbed and flowed. The size of the encampment grew, as did the amenities available to protesters — a kitchen, a medic’s tent, a library and even a tea house. Protesters participated in almost daily marches, and in more confrontational actions, tried to block the doors at the Convention Center during a conservative gathering, broke into an abandoned school building, built a massive barn and tried to occupy Congress. And as other prominent Occupy encampments around the country have been evicted, protesters at both McPherson Square and Freedom Plaza have mostly been allowed to go about their business with little overt interference from the police.

In recent weeks, though, Mayor Vince Gray has asked that they decamp for Freedom Plaza so that McPherson Square can be cleaned up, and a congressional committee grilled the National Park Service over why existing anti-camping regulations weren’t being enforced. The U.S. Park Police has said that it will no longer be so permissive of those that choose to sleep in the park, while some have started to wonder if the Occupy movement has become more about its occupation than about productively combatting income inequality.

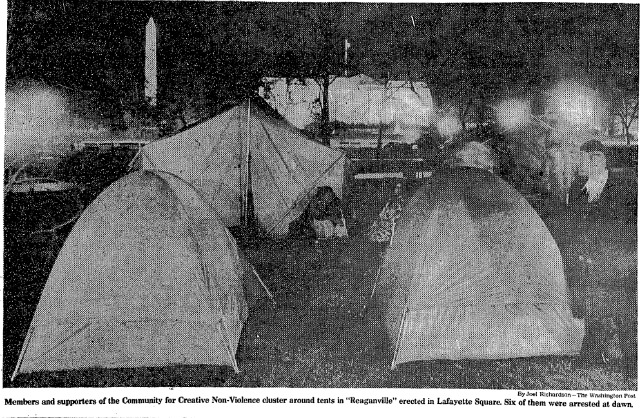

In many ways, the protest and plight of the Occupy D.C. campers is very similar to an encampment set up in Lafayette Park in late 1981 and known as “Reaganville.” In fact, much of what happened then is influencing what could happen now. Wrote The New York Times of Reaganville:

The group said the camp would help dramatize the plight of thousands of homeless people who scavenge for food and sleep wherever they can outdoors, atop sidewalk heating grates, in parks or entrances to buildings.

Organizers of the protest said they planned to continue it through the winter, and that it would also help to ”make increasingly obvious the devastation wreaked by the Reagan Administration’s drastic cutback in social spending.”

On Wednesday, the group sought to obtain a temporary injunction to prevent the police from interfering with the camp protest. Lawyers from the American Civil Liberties Union argued that the protest was a form of ”symbolic speech” deserving protection under the First Amendment.

That legal battle ended in a Supreme Court decision in which the majority of the justices found that National Park Service regulations against sleeping were reasonable enough to pass constitutional muster. During a court hearing yesterday, a federal judge used the case as a justification for denying a request by one Occupy D.C. protester that the Park Police be prohibited from enforcing the ban on camping.

The question of course remains: what next for Occupy D.C.? As other movements in other cities have shifted their focus and tactics, even Katrina vanden Heuvel, editor-in-chief of the left-leaning journal The Nation, wrote today in the Post that maybe it’s time for protesters to move out of their tents and start engaging the political process in a more significant way. There’s little doubt they’ve changed the tone of the conversation over inequality, but what that means moving forward remains up in the air. (The Center for Creative Non-Violence, which was behind Reaganville, used its protests to force President Reagan into agreeing to providing funds to rehab a local homeless shelter it now runs.)

On this four-month anniversary, though, there is one way that Occupy D.C. protesters likely don’t want to be like their predecessors—Reaganville closed down four months after it was established.

Martin Austermuhle

Martin Austermuhle