Photo by Joe Flood

Photo by Joe Flood

More than 15 years before police use of force became a topic of urgent national discussion, the Metropolitan Police Department confronted it head on through a voluntary oversight process. Now—after the agency underwent a Department of Justice review and completed another six years of monitoring—the D.C. Auditor commissioned a report to see how MPD has fared in the ensuing period. The overall verdict: pretty well, though the department still has some “significant deficiencies” to address regarding reporting and investigating use of force incidents.

“There’s no evidence that MPD has an excessive use of force problem,” said Michael Bromwich, a consultant who was hired to conduct the review. “The bottom line is the reforms are still in place and they continue to be managed by people that care about them.”

Added D.C. Auditor Kathy Patterson: “D.C. remains best in class on this issue.”

Back in 1998, the Washington Post did a five-part series that found, among other things, that MPD officers fired their weapons at more than double the rate of other major police departments (for comparison: D.C. officers were involved in 640 incidents between 1994 and 1998. That was 40 more than the Los Angeles Police Department, which policed a population six times the size with twice as many officers). The series also highlighted issues with how MPD investigated incidents involving use of force.

The following year, then D.C. Mayor Anthony Williams and then MPD Chief Charles Ramsey invited the DOJ to conduct an investigation (while the DOJ had investigated other departments, it was the first time they were invited in). After two years, they found major issues with use of force training, investigations, policies, and systems. While “well-managed and adequately-supervised departments” would have an expected rate of 1-2 percent use of excessive force, about 15 percent of MPD’s use of force incidents were excessive, the DOJ found, according to the auditor’s report.

In 2001, D.C. signed a memorandum of agreement, which mandated a specific set of reforms as well as an oversight group to ensure that they were being carried out over a five year period. Bromwich, who also conducted the recent audit, led the monitoring team at the time. The five year period was extended to six, but in 2008, the team recommended they put an end to the MOA and monitorship. In other cities under similar purview, the process has taken significantly longer.

“We put in blood, sweat, and tears,” said Police Chief Cathy Lanier, who took over the department in 2007, at a press conference today. “We were here before the MOA. We all lived through going into the MOA … We have a lot at stake to make sure that those reforms were not for naught.”

And so it was with genuine felicity that she read out the report’s findings regarding use of force. The auditors “took a lot of our time,” she said with a laugh, “I think it was time well spent to know that we respect and treat our residents very well.”

Courtesy of the D.C. Auditor

Courtesy of the D.C. Auditor

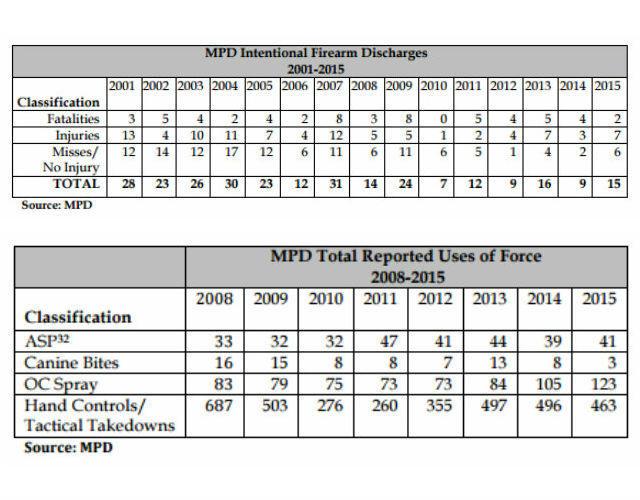

Since 2001, when oversight began, the report shows a steady decline in the average number of intentional firearms discharges: from the five-year period between 2001 and 2006, the average was 26; from 2006-2010, it was 17.6; and from 2011-2015, it dropped down to 12.2. That represents a 50 percent reduction over that time period.

“Although the Review Team identified problems with the process that has been in place to review officer-involved fatal shootings—centering on the length of time it takes to consider the case for potential prosecution—the data do not support any claim that MPD officers use their firearms excessively,” the report concludes.

“This is a big deal,” said D.C. Council Chairman Phil Mendelson, because the analysis was conducted in the absence of a major controversy. “So often, analysis or review or investigation of police incidents—and I mean that very broadly—are done on a reactive basis. That’s not the case here.”

There have been several recent high-profile incidents—including the detention of UDC freshman Jason Goolsby after visiting an ATM or the death of Alonzo Smith after being in custody of special police officers—though MPD said its actions were justified in the first case and is actively investigating the second.

Black Lives Matter activists, though, have continued to highlight those incidents and have pushed back on proposals to expand police patrols amid a spike in crime. Mayor Muriel Bowser struggled to present her “Safer, Stronger” legislation last year amid chants of “We don’t need more police!” and “We want jobs!”

Still, the report issued 38 recommendations to address “some significant deficiencies in key areas covered by the MOA.” The criticisms include the declining quality of investigations into use of force, systemic problems (both from MPD and United States Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia) that resulted in “excessive delays in resolving officer-involved fatal shootings,” and changes in the requirements for reporting use of force.

The auditor took MPD to task, for example, for ending the practice of investigating certain uses of force, including takedowns, unless there is a complaint or injury reported. “We think those modified reporting and investigations thresholds, especially with respect to takedowns, are inconsistent with law enforcement best practices,” the report reads.

Of the recommendations, MPD agreed in whole or in part to 28 of them.

“The community has to trust the police,” Mendelson said, saying the D.C. Council would look to the report to help it conduct oversight. “There is no faster way of souring that relationship than abuses of police authority such as excessive and unwarranted use of force.”

The Auditor’s Office plans to share the report with police experts around the country as many jurisdictions begin, or are in the midst of, grappling with similar issues that D.C. faced at the turn of the millennium, some of which remain ongoing. D.C. police executed a search warrant on a family’s house for someone who doesn’t live there—and pointed a gun at two young children, FOX5 reported today.

Of the takeaways for other cities who are just beginning oversight processes, Lanier said, is that it comes with “an awful lot of work” but it also “brings with it the commitment from the entire city to get the job done, if that means budgetary support, support from the city council.”

Rachel Sadon

Rachel Sadon