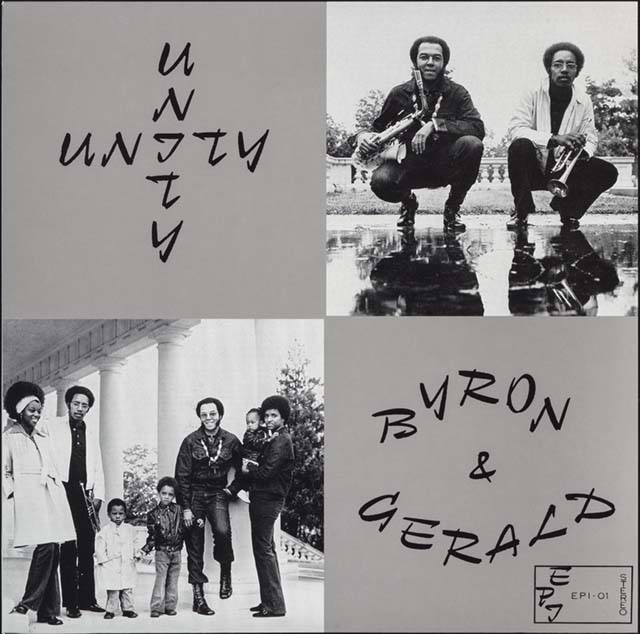

(Courtesy Eremite Records)

(Courtesy Eremite Records)

Washington is home to one of the premier DIY record labels. But long before Dischord, local musicians ventured outside the established music industry to release vinyl records on their own private labels. This is the latest in an occasional series that revisits these private press records and the musicians that made them.

Byron Morris is an electrical construction engineer by trade. He also played saxophone on one of the most energetic avant-garde records to come out of Washington’s jazz scene.

Eremite Records has just reissued the classic album Unity, credited to Byron and Gerald, recorded in 1969. It brings back memories of a volatile era. In his liner notes to the reissue, Morris writes, “I can still smell the tear gas & the burning tires…but the music got us through that time.” So he doesn’t want to talk about politics, then or now; he wants to talk about music.

“I’m 76,” he told DCist. “When I recorded that…I was a young guy full of ambition. John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman were my role models in music. We wanted to do something and make a statement.”

That statement was recorded at an experimental television studio at Howard University on March 22, 1969, and the road to that session goes through the history of jazz in Washington.

Morris was born in Roanoke, Virginia, the son of a jazz musician who, because he had seen what that life is like, did not want his son to follow in his footsteps. Morris earned a degree in electrical construction engineering from the Tuskegee Institute and came to Washington in the early ‘60s, working briefly for the Otis Elevator Company and then for the consulting engineering firm, Shefferman and Bigelson.

Despite his father’s objections, though, he had taken up the saxophone. In D.C., he began to frequent local jazz clubs like The Crow’s Toe, which used to be at 10th and K Streets downtown and ran all-night jam sessions on Friday and Saturday nights.

That was where Morris met fellow musician Gerald Wise—Gerald on Unity. The two went to local jam sessions, like those held by the Left Bank Jazz Society of Washington, D.C.

One night Wise called up Morris to tell him that alto sax player Jackie McLean was going to play at the Showboat (now the Songbyrd Café). McLean was running late and the club needed music, so Morris and Wise sat in with trumpet player Woody Shaw, along with local musicians Fred Williams (bass), drummer Eric Gravatt (both of whom would play on Unity), and the late Buck Hill.

At the jam session, “Woody looked over at me and smiled,” Morris said. “I wasn‘t playing on the changes like the older guys, I had a newer way of playing. Woody was playing off the pentatonic scale and I was picking up on that. So you had two different generations of musicians playing but we were able to make it sound good.”

Inspired by the growing experimental music scene, but not finding many in the Washington area who played that way, Morris and Wise got a group together for a recording session at Howard University. Gravatt recruited musician friends from Philadelphia, saxophonist Byard Lancaster and percussionist Keno Speller.

Byron Morris and Gerald Wise today (Michael Wilderman)

Byron Morris and Gerald Wise today (Michael Wilderman)

Nearly 50 years later, Morris is still impressed that these players were all too happy to contribute. “These guys from Philly, nobody said, ‘Who’s going to pay for the gas?’ None of that. It was a different time. Guys were just interested in getting together and exchanging ideas and thoughts. That was more important than money.“

Morris also remembers the energy level at the recording session being so elevated that some of the musicians did push-ups when they weren’t playing.

There was still one problem: Though they had a tape of a great session, there were no plans to release it. Vassar College turned out to be the unlikely savior.

After moving to Poughkeepsie to work for IBM, Morris joined a local jam session, and it was there that he caught the attention of sax and trumpet player Joe McPhee, who taught music at Vassar. McPhee asked Morris to join his band at an upcoming concert at the college.

”You had to be rich to go to Vassar, there was no two ways about that!,” Morris remembers. He also recalls the crowd going wild for McPhee’s high-flying free improvisation.

“The audience went absolutely crazy…they were just jumping up and down and screaming,” Morris says.

College students cheering for jazz?

”This was the time of the avant-garde,” Morris points out. “This was the latest thing! They ate it up! A lot of these girls had spent time in Europe, going around the world looking for things that were different.”

McPhee encouraged Morris to start his own label and release Unity, which didn’t sell but got a rave review in Downbeat magazine. Nearly fifty years later, this under-appreciated recording may again land on fresh ears.

Previously on Washington’s Homemade Records:

Danny Gatton

‘Thesda

Kath/Val Rogolino

George Smallwood

Paradigm/Wicked Witch