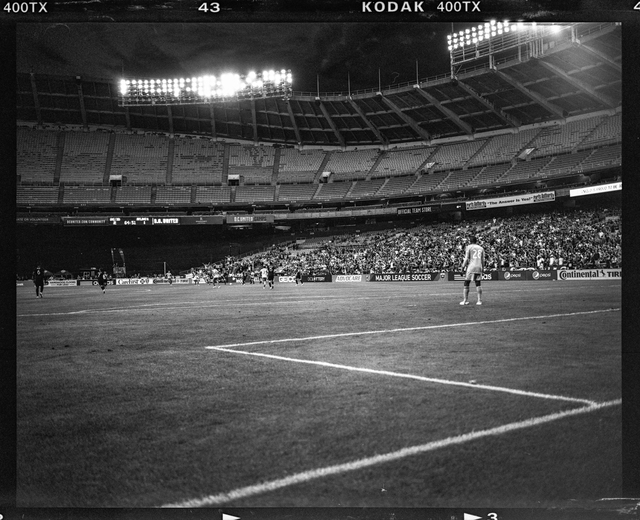

RFK Stadium earlier this summer. Photo by Pablo Iglesias Maurer.

By DCist contributor Charles Boehm

D.C. United are set to play their last match at RFK Stadium on Sunday, capping a 22-year homestand at the ancient bowl on East Capitol Street with their 2017 MLS season finale against the rival New York Red Bulls.

Sometime next summer United will move into Audi Field, their new, “soccer-specific” home at Buzzard Point, marking the departure of RFK’s last full-time tenant. Events DC plans to continue operating it as short- and long-term plans for the wider RFK campus are finalized and enacted, but it’s all-but-certain to meet the wrecking ball at some point in that process.

Photos by Pablo Iglesias Maurer.

RFK was home to a litany of D.C. teams over the decades, including the Nationals, the area’s local (American) football team, two editions of the Senators, and a range of concerts and events. Many are happy to bid farewell to the decaying arena and its tattered, humble features, which don’t hold a candle to the amenities fans find at the Capital One Arena, Nationals Park, or FedEx Field. But it’s truly the end of an era for D.C. sports, especially for those who continue to find the city’s newer facilities lacking in a few key departments, namely history, community and soul.

“To me it felt like a living memory of what D.C. sports in the ‘80s were,” the Washington Post’s Dan Steinberg, who’s attended games at RFK as both a spectator and a reporter since moving to the city in 1998, told DCist. “It’s something that no one will ever say about FedEx Field, for whatever reason—it doesn’t feel like anything there. [RFK] feels like so many people had so many good times there.

“It got old, for sure, a long time ago, but there was something charming, at least for a little while, about a place where a sinkhole might open up next to where you were standing.”

The District Ultras. Photo by Pablo Iglesias Maurer.

Steinberg’s first residence in D.C. was a small apartment in Capitol Hill, and he quickly discovered the informal local ritual of walking to United games at RFK, tailgating in Lot 8 then raising hell in an antiquated stadium where no one paid much mind to small matters like broken seats, loud and occasionally foul-mouthed singing, chanting and drumming, or the occasional piece of pyrotechnics.

“It just felt so different from going to other stadiums. No one cared what happened there,” he said. “It was so well-worn that it almost didn’t matter how you behaved … But also it made it feel like a home, in a way.”

RFK has been called American soccer’s version of the CBGB club, New York’s defiantly low-fi punk and new wave anachronism. A more fitting local comparison might be the original 9:30 Club, which performed a similar function in Washington long before the era of gentrification descended on the city.

Like the 9:30 Club on F Street, RFK grew famous for both its seediness and its people-first aesthetic, with spectators proudly boasting harrowing tales of inebriation, overcrowded conditions and king-sized rodents.

Photos by Pablo Iglesias Maurer.

Jason Anderson is a longtime United supporter dating back to the team’s inaugural 1996 season who writes for fan site BlackandRedUnited.com. Even as an adolescent, he realized immediately that RFK was different, recalling two Spanish-speaking fans in his section who snuck an unmarked bottle of an unknown liquor into the stadium and readily shared a swig or two with the father of one of his friends.

“’When is there going to be trouble from this?’” Anderson remembers wondering. “Looking around, it was like, ‘There’s no coming. There’s nobody that’s going to say no about this at all.’ I started to learn right then and there: This is different from everything else, this is its own animal.”

While most MLS teams focused solely on the suburban “soccer mom” demographic in the early years, D.C. United’s leadership made the fateful decision to both welcome a diverse band of hard-core supporters and give them space to create the atmosphere that distinguishes soccer from other sports.

Photos by Pablo Iglesias Maurer.

Founding president Kevin Payne recounts a conversation with team administrator Betty D’Anjolell—both are now enshrined in the club’s “Hall of Tradition”—a full year before the team first took the field.

“I was kind of assuming we’d have an official fan club,” said Payne. “And she convinced me that we shouldn’t do official fan clubs, and we shouldn’t be too involved with them as a club, other than to support them—that we should let the fan clubs develop their own culture based on what their members. And that was a critically important decision.”

Today MLS and American soccer in general have become much more hospitable to those exuberant displays of support rarely allowed in other U.S. sports. Payne credits the Screaming Eagles, Barra Brava, and other United supporters groups—as well as longtime RFK manager Jim Dalrymple—for setting a different tone at RFK.

RFK Stadium in 2013. Photos by Pablo Iglesias Maurer.

“[Dalrymple] was open-minded enough and supportive enough to allow us to allow our fans to do things that really nobody else was allowing at any of their stadiums,” said Payne. “Our fans could act in a way that might be a little frightening to a lot of stadium managers, and ultimately created a very, very special atmosphere.”

With close to 40,000 fans expected at Sunday’s finale—more than twice the usual crowds of recent seasons—United supporters old and new plan to make the farewell game one last rowdy party before opening a new era at a clean new home next year. Kickoff is at 4 pm.