Photo by Tim Brown.

Photo by Tim Brown.

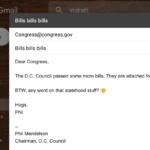

D.C. does not have a full-fledged member of Congress on Capitol Hill, so the District’s representatives have to get crafty.

Eleanor Holmes Norton, technically a “delegate,” lacks a floor vote in the 115th Congress.

She spends a lot of her time trying to ensure that policy riders, extra provisions added to a bill that don’t necessarily have anything to do with the topic at hand, don’t pass. Legislators from other jurisdictions often slip in D.C.-specific policies. The Dornan Amendment, for instance, prevents D.C. from using its locally raised funds to fund abortions. Another rider blocks the sale of marijuana in the District.

But now, Norton is trying to add a few riders herself.

“We don’t object to riders—we object to undemocratic riders,” Norton says. “We object to riders that fly in the face of what the local jurisdiction requires.” She hasn’t decided which bills to attach them to yet.

Her staff has been “combing the code” to find laws that specifically affect D.C. residents in odd ways.

They found one in the National Capital Revitalization and Self Government Improvement Act of 1997, a wide-ranging piece of federal legislation that passed when the city faced a financial crisis. It called for the federal government to fund the D.C. court system, federal agencies to handle D.C. probationers and parolees, and the Bureau of Prisons to house D.C. felons.

It also has a provision that Norton characterizes as “redundant, unnecessary and insulting”—it made it a federal crime to obstruct any bridges connecting the District of Columbia and the commonwealth of Virginia. Anyone convicted of the misdemeanor faces a fine between $1,000-$5,000 and up to 30 days imprisonment.

By the time the bill passed, though, it had already been illegal to obstruct a public road in D.C. for decades.

Norton says the measure stems from Virginia legislators frustrated by street blocking, a protest tactic used by the group Justice for Janitors in the mid-nineties. In September 1995, for instance, demonstratorsblocked the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Bridge, causing traffic backups for several miles that also affected the Memorial, 14th Street, and Key bridges, per Washington Post reports from the time. The protest led to 34 arrests.

“You could see if MPD hesitated, but there’s no such thing,” says Norton. “It’s just some members of Virginia who said, “Oh no you don’t.’” She adds that there’s no similar misdemeanor for blocking a bridge between D.C. and Maryland.

Norton’s office also found a measure on the books that allows the president to federalize D.C.’s police department “as the president may deem necessary and appropriate.” While there’s no instance of the president taking advantage of this power, Norton introduced legislation to strip that authority.

She says part of her office’s work in compiling these instances is to get ready for the possibility of Democrats taking over Congress after the midterm elections, so they can get rid of these measures entirely.

But she can’t afford to write off riders or Republicans, either. “Most of them are instinctively against the District of Columbia,” she says. “But you’ve got to find ones you can work with because otherwise the District is really lost—we’ve been in the minority for most of my tenure.”

The thing that gives Norton the most hope about getting rid of this bridge-blocking federal misdemeanor is that “nobody cares about this but us. This is not the D.C. gun laws. I don’t think Republicans care about them and that may be the best argument for getting them off the books.”

She’s encouraging D.C. lawmakers to try repealing this part of the federal law, too. The District has been able to repeal pre-Home Rule laws that only affect D.C., and she’d like to see if the courts would similarly uphold repeals of laws passed after 1973.

But this isn’t just about a bridge-blocking law. Norton says that she’s also seeking out these laws as a method of reminding people of D.C.’s odd legal limbo when it comes to the federal government. “We’re looking for as many ways as we can to draw attention to the unequal status of the District and to say, “Does this make sense to you?’”

Rachel Kurzius

Rachel Kurzius