Long before she was infamously arrested in 1955 for refusing to relinquish her seat to a white man on a segregated bus in Montgomery, Alabama, Rosa Parks rejected the racism that made African Americans second-class citizens in their own country.

In an undated note, the future civil rights icon recalled standing guard with her shotgun-toting grandfather at the age of six while the Ku Klux Klan paraded through their Alabama neighborhood in 1919.

“I stayed awake many nights, keeping vigil with Grandpa,” Parks writes in her delicate cursive. “I wanted to see him kill a Ku Kluxer. He declared the first to invade our home would surely die.”

A portion of this quote, along with other rarely seen handwritten notes, letters, manuscripts, photographs, records, and memorabilia, comprise a new exhibition at the Library of Congress called Rosa Parks: In Her Own Words. It’s pulled from a collection of 10,000 items that document her and her family’s lives from 1866 to 2006.

“This new exhibit is an important milestone for Rosa Parks to tell her story beyond the bus for new generations that can learn from her, and through her words and her pictures,” Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden told reporters at the exhibition’s preview on Wednesday.

The exhibition opened Thursday, which marked the 64th anniversary of the Montgomery bus boycott that followed Parks’ arrest. It uses her writings—sometimes on the fronts and backs of documents, envelopes, and even a pharmacy bag—to frame her story. And in doing so, it upends the sanitized version that misconstrues her as a dainty, petite seamstress who was too tired to give up her seat on the bus. A companion book called Rosa Parks: In Her Own Words was written by Susan Reyburn of the Library of Congress and includes the anecdote about Parks standing watch with her grandfather.

“[Visitors] would be surprised to know she had this feistiness, that she was a rebel from the beginning, because you don’t see that,” Adrienne Cannon, the exhibit’s curator, tells DCist.

Born in 1913, Parks learned from an early age to never accept mistreatment, and was already a hardened freedom fighter long before she boarded that bus.

In the 1930s, she and her activist husband Raymond Parks helped save nine black teenagers known as the Scottsboro Boys who were falsely accused of raping two white women, and sentenced to death in Alabama.

And in 1944, more than a decade before she was arrested for refusing to surrender her bus seat to a white man, Parks worked as an investigator for the NAACP to determine why Recy Taylor, a black, Alabama woman gang raped by six white men, was not getting justice—the men responsible were never punished.

Parks’ work investigating interracial rape cases, which were common in the South, may have been fueled by her own experience with sexual assault. When she was working as a housekeeper for a young white couple in 1931, Parks revealed that the couple’s white neighbor tried to rape her.

“He was fast becoming intoxicated on alcohol and lustful desire for my body,” she writes.

Attorney Fred Gray, now 88, defended Parks after she was charged with disorderly conduct for refusing to give up her bus seat. She was ultimately found guilty and fined $14.

Gray and Parks had gotten to know each other through their civil rights activities—his law office stood a block and a half away from Parks’ job at Montgomery Fair department store, and she lived near his church. The two remained friends until Parks’ death in 2005.

“From the time I opened my office in September of ‘54 until the day of her arrest, almost every day she would walk from her store where she assisted the tailor, to my office, and we would talk about the problem including the problems on the buses and what one should do in the event they were asked to give up their seat and if they decided not to do so,” Gray tells DCist.

Parks wasn’t the first black woman to challenge Alabama’s segregated bus system.

Gray also represented Claudette Colvin, who had been arrested and charged with disorderly conduct nine months earlier for refusing to turn her bus seat over to a white woman. The NAACP sought a test case to argue against segregation and Gray was ready to file a lawsuit on Colvin’s behalf, but the organization wasn’t, in part because she was an unwed, pregnant teenager.

“So we concluded that what we would do is keep a record of everything that happened from Claudette Colvin forward, and the next opportunity that presented itself, we would be ready to do whatever it took to end (segregation),” Gray says. “That opportunity came on … December the first of ’55.”

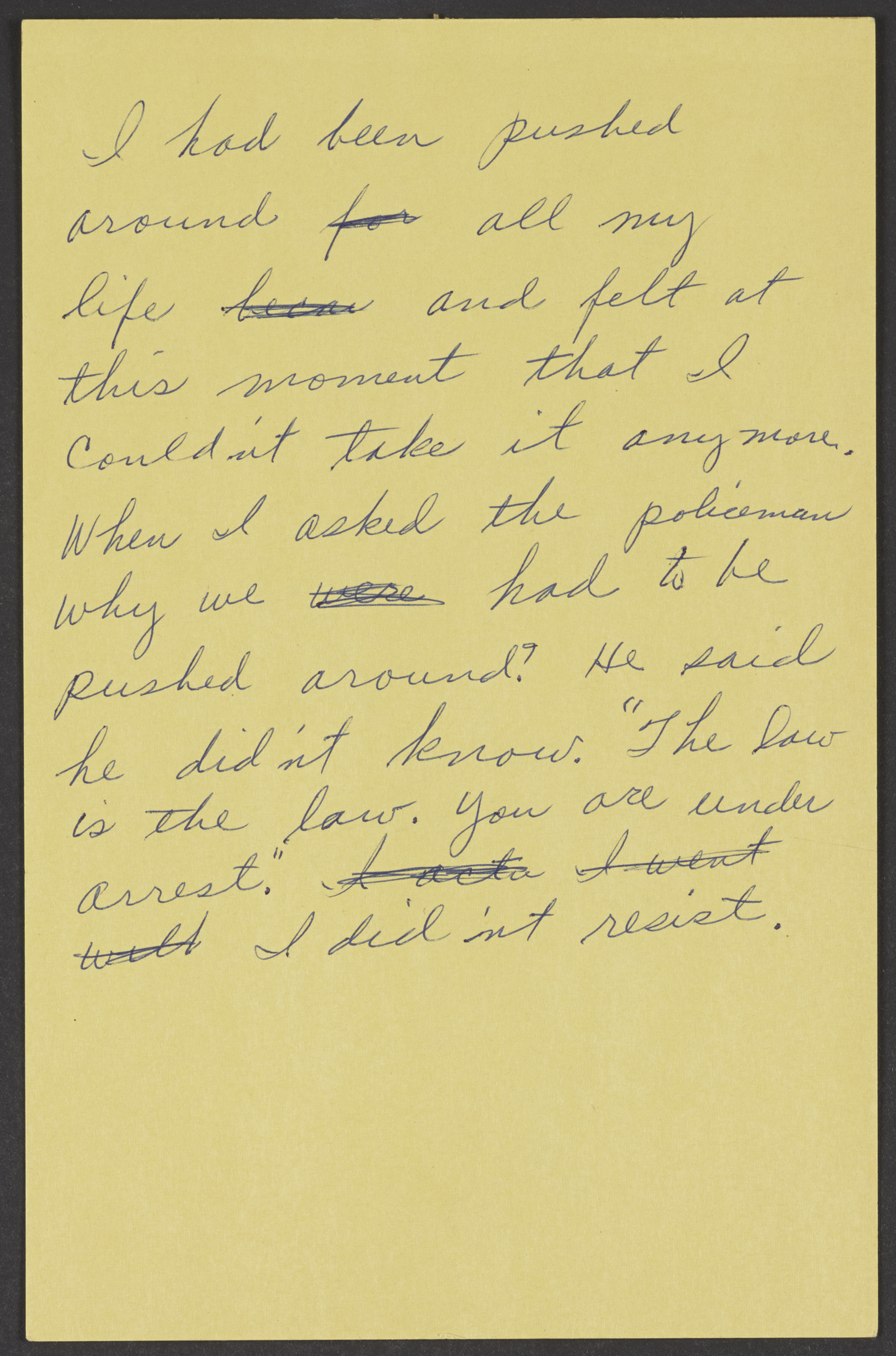

That was the day Parks was arrested. Reflecting on her defiance, Parks wrote, “I had been pushed around all my life and felt at this moment that I couldn’t take it anymore.”

The whitewashed version of Parks’ activism persists in part because the NAACP thought she was an “ideal candidate” for a test case against Jim Crow, Cannon says.

“She was respectable, church going, a secretary of the NAACP—she had a sterling reputation and so that was done initially in order to advance the test case that the NAACP wanted to file as a federal lawsuit,” Cannon says. “And also, she maintained the persona to advance the bus boycott in the civil rights movement at large and she did that for decades afterwards. And then she became sort of trapped in that image on the bus.”

Parks knew she was a symbol of the movement and literally paid the price for her activism.

Not only did she receive constant death threats and enter dire poverty, but her infamy made it difficult for her to remain employed, prompting the couple and Parks’ mother to ditch Alabama and move to Detroit in 1957. Rosa Parks briefly relocated to Virginia after securing a hostess job at the Hampton Institute’s Holly Tree Inn guesthouse before returning to her husband in Detroit the following year.

The Parks’ 1959 income tax return, on display in the exhibition, shows she and her husband reported a combined annual income of $661.06. Four years earlier, they had recorded their joint annual income at more than $3,700. Even so, her activism continued for decades.

Parks supported Shirley Chisholm’s congressional and presidential campaigns in the late 60s and early 70s as well as both of the Rev. Jesse Jackson’s runs for president in the 1980s. She also fought for women’s rights and against the Vietnam War. And she took part in anti-apartheid protests against South Africa in the mid 1980s.

Photos in the exhibit from the 1980s also show Parks practicing yoga and posing with actress Marla Gibbs on the set of 227, an African American sitcom set in Washington, D.C. In 1995, Parks spoke at the Million Man March and four years later, she received the Congressional Gold Medal from President Bill Clinton.

About a year before Parks died at the age of 92, Gray visited her for the last time in Detroit. But instead of talking about civil rights, Gray recalls asking Parks how he could help her as her health declined. Her remembers her saying said she was doing well.

“I think if she were here today … she would be happy that she’s being honored,” says Gray, who is still practicing law in Alabama. “But I think she would also tell us that the struggle for equal justice continues, and that we haven’t finished the job yet.”

Rosa Parks: In Her Own Words is on display at the Library of Congress through September 2020. FREE

There’s No Paywall Here

DCist is supported by a community of members … readers just like you. So if you love the local news and stories you find here, don’t let it disappear!