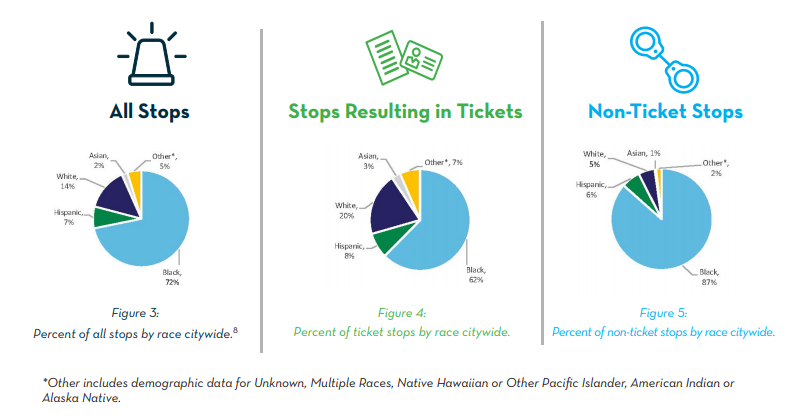

The Metropolitan Police Department published a new set of stop-and-frisk data this week, confirming the racial disparities in enforcement found in the city’s first-ever release of such data last September. Nearly three-quarters of the police stops conducted between July 22 and December 31 last year—72 percent—were of black people, a roughly similar proportion as reported in the earlier release, even though black residents currently make up only 46 percent of D.C.’s population.

Meanwhile, 14 percent of the stops were of whites, 7 percent were of Hispanics, and 2 percent were of Asians. Among stops that did not result in traffic tickets being issued, black people represented a whopping 87 percent, compared to 62 percent for stops that did result in tickets. (For context, white people make up 37 percent of the District’s population.) The new data covers over five months, whereas the earlier data covered just the first four weeks of the entire period. Around 63,000 total stops were recorded.

Stop-and-frisk—and the broader issue of racial profiling—has come under scrutiny in cities across the country, receiving particular focus recently in part because of the just-suspended presidential campaign of former New York City Mayor Mike Bloomberg. During Bloomberg’s tenure, the New York Police Department’s use of the tactic was deemed unconstitutional by a federal judge.

D.C. police are collecting and releasing these figures as the result of a years-long legal battle with the local chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union. The ACLU repeatedly sued the department to have it comply with a 2016 law known as the Neighborhood Engagement Achieves Results (NEAR) Act, which, among other things, called for more information about who MPD is stopping and why, and the results of those stops.

A spokesperson for the civil rights organization declined to comment on the new data, pending further analysis. ACLU-D.C. has long reported on racial inconsistencies in policing: Its own data from 2013 to 2017 shows that, in the District, black people have been arrested at 10 times the rate of white people. (When the first batch of the MPD’s stop-and-frisk data was released in September, ACLU-D.C.’s Scott Michelman told WAMU it “confirms what we’ve been hearing from community members for years.”)

The police department says it’s too soon to conclude that its officers’ stops are prejudiced. “It may be tempting to point to this data as evidence that stops are biased,” the report says. “However, while the new data collection is an important step forward in understanding stops, additional data and comprehensive analysis will be necessary to determine whether stops are biased.”

The data was discussed Thursday at a public oversight hearing about the department held by the D.C. Council’s judiciary committee. The chair of that committee, Ward 6 Councilmember Charles Allen, pressed Police Chief Peter Newsham about increased complaints regarding invasive searches, including a recent lawsuit in which a D.C. resident alleged he was sexually assaulted during a warrantless search.

At the hearing, Newsham said officers can legally pat down—or “frisk”—people if the officers have reasonable suspicion that someone is carrying a weapon. People often hide weapons, including illegal guns, “in their crotch area,” he added, citing the use of compression shorts.

Allen responded that the vagueness of the term “crotch area” in MPD’s policy has led to “degrading” searches. “I don’t have a problem looking at the policy and making sure it’s more specific,” Newsham said. “We don’t want to humiliate someone by a public search, which may be a legal necessary search. We should do that in private.” He added that most invasive searches by D.C. police involve suspects who have been arrested and are in custody.

The new report also features other data on stops. For instance, 87 percent of stops were resolved without a pat down or pre-arrest search, while three in four were resolved in 15 minutes or less. And for every 100 stops, 61 produced a traffic ticket and 21 produced an arrest (the remaining 18 were conducted “as part of a public safety inquiry”). In total, 700 guns were seized following stops, according to the department.

MPD says it’s partnering with independent researchers, such as those at the Georgetown University Law Center, to assess bias in stops more clearly. On Thursday, Newsham also pointed to the department’s body-worn camera program as transparency effort, saying the public can review footage from the cameras. (However, such footage can be withheld under certain circumstances outlined in the law, and it can also be expensive to obtain owing to processing fees.)

Looking ahead, the police department says it will update its stop-and-frisk data online twice a year and release an annual report.

Elliot C. Williams

Elliot C. Williams