As our region moves into colder months and a possible second wave of the pandemic, residents wait for a promised vaccine that will return life to some semblance of normalcy.

But when that vaccine arrives, how will the local health apparatus mobilize to distribute it? Who will get it first? And will it be mandated?

We read local governments’ COVID-19 vaccination plans to get the answers to those questions.

Earlier this month, both Virginia and Maryland issued preliminary vaccine plans, which have many similarities to one another. D.C has no publicly available plan (the city has declined to release a plan even in response to a journalist’s Freedom of Information Act Request). But earlier this week, Health Director LaQuandra Nesbitt told members of the D.C. Council that the plan is to get the vaccine to healthcare workers first—regardless of whether or not they live in the District. District residents who are at a higher risk of severe COVID-19 illness, especially people 65 years or older, would be next.

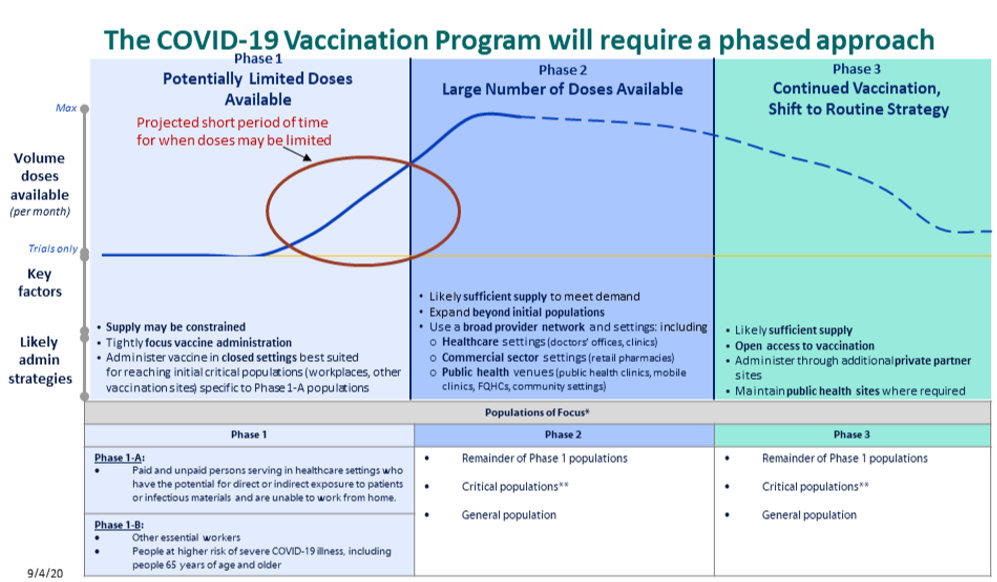

That order of operations is similar to the plans laid out by both Maryland and Virginia, who have separated their vaccine plans into three phases, in accordance with CDC recommendations.

The first phase would have limited doses of the vaccine, and the first people to get vaccinated in each state varies. Maryland’s plan states that “paid and unpaid persons serving in healthcare settings who have the potential for direct or indirect exposure to the patients or infectious materials and are unable to work from home” will be in Phase 1-A of the plan. After those people, other essential workers and people at higher risk of severe COVID-19 illness can get the vaccine (Phase 1-B).

However, Dr. Eric Toner, a senior scholar and scientist with the Johns Hopkins University’s Bloomberg School of Public Health, asks, “what do you do if there’s not enough vaccine for everybody in the first tier?”

State officials acknowledge that they don’t know how much of the vaccine will be available in the first phase. The report says that 14 percent of Marylanders, or more than 770,000 residents, will fall into phase one.

Virginia is planning to leave it up to each individual jurisdiction to determine sectors of the critical workforce that are most essential and at risk, using the example of port-related workers in a coastal jurisdiction.

The plan also notes that those in racial and ethnic minority groups, including tribal communities, should be considered for a vaccine in the earlier phases due to these communities being disportionaly impacted by COVID-19. Also, folks in congregate settings like correctional facilities, homelessness shelters, and universities should also be considered.

The second phase would have an increased supply of vaccine doses available and could be provided to a larger network of healthcare providers.

“If we’re at 90 something percent of those in phase one that are vaccinated, then we can start moving to phase two in vaccinating some other groups,” Kurt Seetoo, chief of the center for immunization at the Maryland Department of Health, told WAMU/DCist.

In Maryland, the department of health is responsible for creating a database of pharmacies, physicians, and clinics that want to distribute the vaccine to the public. Seetoo says the database is something they didn’t do during the Swine Flu pandemic in 2009.

“By doing it this way will be more efficiently able to register providers to get covered vaccines and they will be able to order through the [provider database],” Seetoo says. “In Maryland, we do have a reporting law that all doses administered need to be reported…by having [the database] in place, we will be able to more accurately track how many doses of the COVID vaccine have been administered and…we’ll be able to maybe break it down by jurisdiction.”

The third phase would have continued vaccination with open access to the vaccine and statewide public service announcements encouraging people to get the vaccine.

Virginia Department of Health’s director of immunization Christy Gray says that administering a COVID-19 vaccine should have a lot of similarities to how folks get their flu shots.

However, Dr. Amira Roess, a professor of epidemiology at George Mason University, says that transmission properties of COVID-19 could make this an inaccurate comparison. “You don’t want to have crowds of people showing up to the local pharmacy to get a [COVI-19] vaccine,” says Roess. “How many people can you actually vaccinate given the requirement for social distancing?”

Roess says we can actually learn a lot from how flu shots are being provided during the pandemic which we can apply to how a vaccine will eventually be administered.

So far, the Maryland Department of Health and the state’s department of education do not have a plan to distribute vaccines to students and teachers.

There’s also no directive in the Virginia plan about school-age children, particularly those from kindergarten to sixth grade, getting a vaccine. This is because, as of this moment, there are no vaccines in later-stage trials that have been tested on children.

A District spokesperson tells DCist/WAMU that children will likely not be part of the initial phase of vaccine administration due to current trials not including children. The mayor’s office does not currently plan to mandate a vaccine for anyone, the spokesperson said.

There will be costs associated with distribution, something that Virginia’s plan estimates for. The state has earmarked $121 million for insurance costs, refrigeration, and supplies (like alcohol pad and band-aids). Maryland says it will release cost estimates in the coming weeks.

Both states reiterate that once a vaccine is ready, there will be no out-of-pocket costs for anyone who wants it. The federal government is shouldering the costs of the vaccines, each dose could cost somewhere between $4 to $20, according to an NPR article.

Colleen Grablick and Elliot Williams both contributed reporting to this story.

Matt Blitz

Matt Blitz Dominique Maria Bonessi

Dominique Maria Bonessi