For the first time since March, the sixth floor halls of the United Medical Center in Southeast D.C. are full of hope.

That’s because it is the second day that Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine is being administered to the hospital’s physicians, nurses, doctors, and health care workers.

There’s excitable chatter, purposeful conversations, and even a few laughs as staff move in and out of rooms.

“I’m grateful,” says Dr. Jamar Slocum, a physician hospitalist, who moments before had received one of the day’s first doses.

Originally from Raleigh, North Carolina, Slocum’s been working at the hospital for about three years. For him, the choice to get vaccinated was a simple one.

“It’s my duty and my role as a leader [to get the vaccine]. I believe all physicians are leaders … At these times, people look for leaders and that’s one of the reasons I decided to be vaccinated first,” he said.

From now until early next week — a sort of early Christmas present — 250 doses of the District’s initial nearly 7,000 are being given to those at United Medical Center who have been on the frontlines during the pandemic.

“I think it’s part of history — medical history, scientific history and social history,” says Dr. William Strudwick, United Medical Center’s chief medical officer, who got vaccinated Wednesday. “I mean, they’ll be talking about this period in our lives for forever.”

Strudwick says that the science behind the vaccine’s development, how it uses genetic coding rather than bits of the virus, makes it “probably the safest vaccine that’s ever been produced.”

Area medical professionals like Slocum and Strudwick are hopeful about the vaccine. After nearly 10 months of an uphill battle fighting the coronavirus, the D.C. region has seen more than 10,000 deaths related to COVID-19.

Strudwick, a third-generation Washingtonian, has seen first-hand how hard COVID-19 has hit D.C., not only as a doctor but as a native. “I know many people, too many people that have been affected, too many people that have passed away from this virus,” he says.

And the virus has hit the community surrounding United Medical Center (the city’s sole public hospital) hardest. Ward 8 has seen the highest number of deaths from COVID-19 of any ward in D.C. In total, Ward 8 — which is predominantly Black — accounts for nearly 20% of D.C.’s COVID-19 deaths. That mirrors national trends which have found disproportionately higher rates of infections and deaths in Black and Hispanic communities.

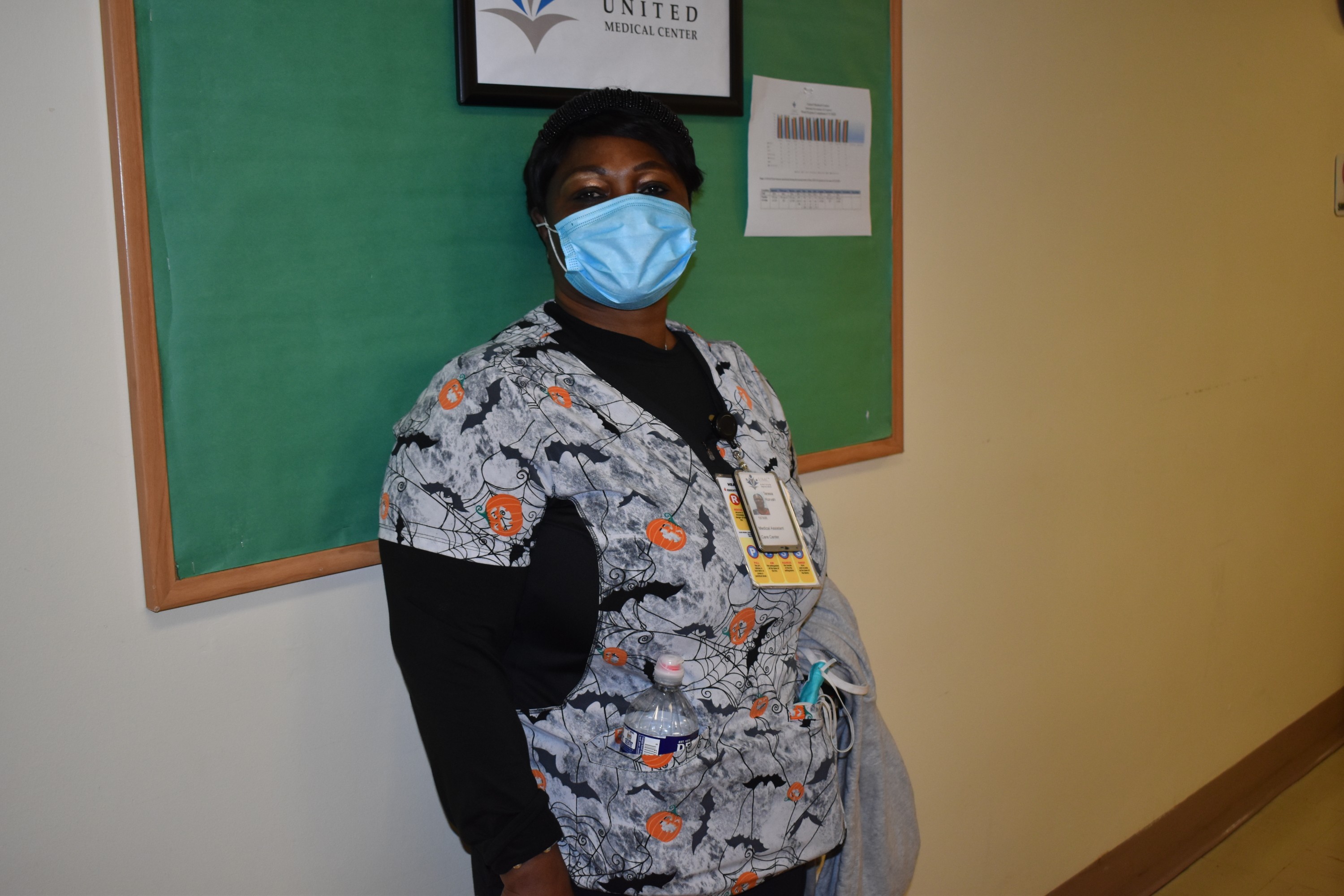

Judy Jenkins-May, a registered nurse at the hospital, says she is getting the COVID-19 vaccine to build trust in it among her peers, many of whom are Black.

“[This hospital] is predominantly, you know, a Black institution,” she says, “When it comes to the government, they are thinking in the past what has happened. The government has always used, you know, brown and Black skin as far as testers … So, [my fellow nurses] just have mixed feelings.”

The United States has a long history of racism in health care and scientific research. Scientists in the infamous Tuskegee experiment allowed hundreds of Black men to die from syphilis as part of a federal study without ever obtaining informed consent. And today, persisting inequities in health care coupled with medicine’s history of racism have underpinned distrust among communities of color, particularly African Americans.

These circumstances are not lost upon Jenkins-May. She’s one of the nurses administering the vaccine and is scheduled to get hers early next week. She says she’s one of only a few nurses at the hospital who has made an appointment to get the vaccine. Jenkins-May attributes much of this to this historic lack of trust, even from Black health care workers.

But that’s why Jenkins-May is here, giving the shots and preparing to receive the vaccine herself in just a few days. “My goal is to encourage them. What we do know is this virus has killed thousands of people. A vaccine is available and I’m front of the line.”

Teresa Korvah knows she will be asked questions about what it was like to get the vaccine when she goes back into the field after the holidays. She’s with the hospital’s mobile testing units, physically going into D.C. communities and neighborhoods to help test for COVID-19, HIV, and the flu.

She has just gotten her first vaccine shot minutes ago.

“[My patients] want to see other people get it first before they get it,” she says, ”And I want to ensure them … that if I can take [the vaccine], they can take the vaccine. The more people get it, it will help other people to get it.”

Asked what it felt like to be one of the first in the city to get the vaccine, Korvah says, “I feel proud … I feel special.”

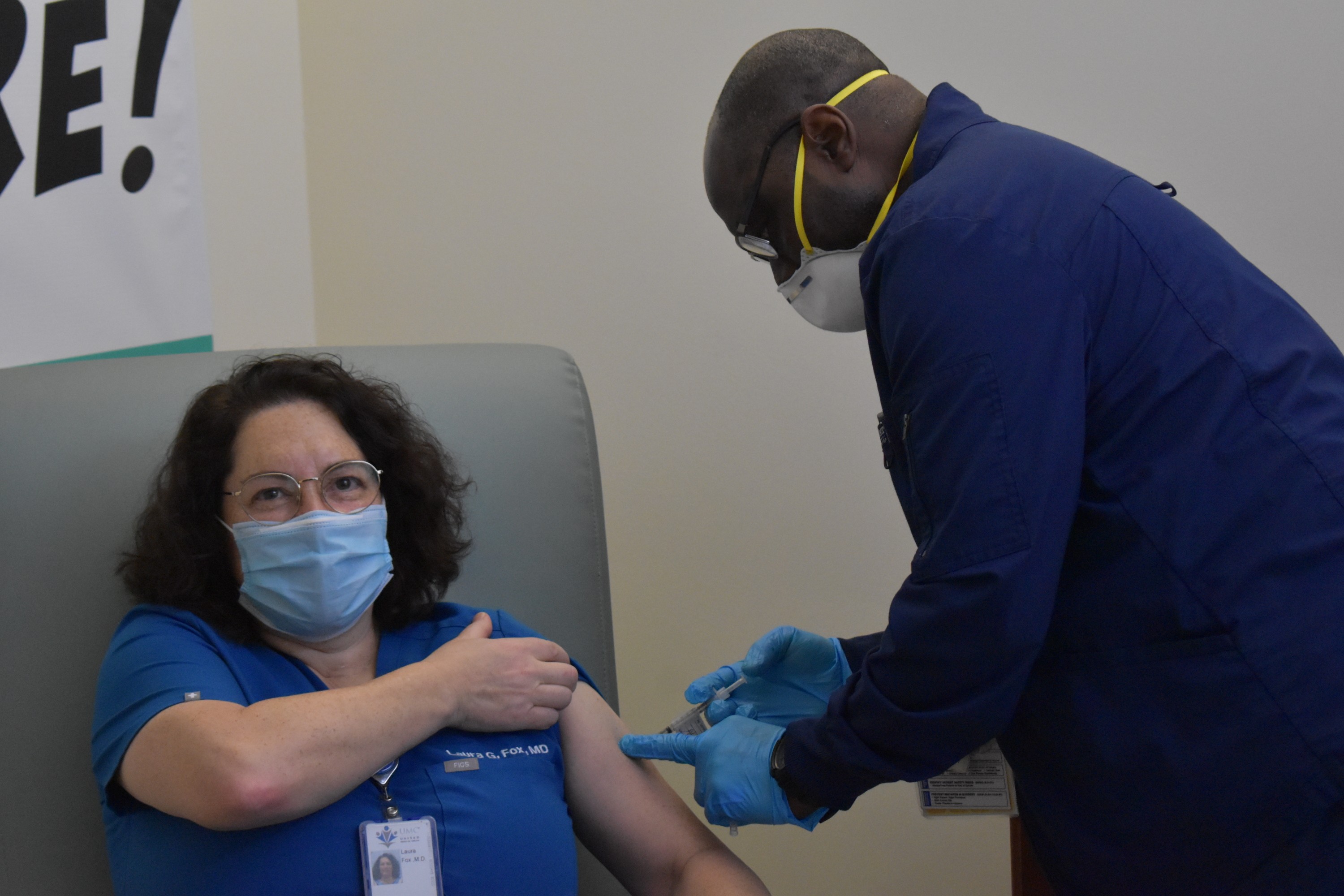

Dr. Laura Fox admits she has felt a bit overwhelmed sitting in the chair, waiting for the needle. She’s an emergency physician at United Medical Center who also received the vaccine today.

“I was overwhelmed by how so many very, very great people came together to make this vaccine for me. And for you,” says Fox, a Northwest D.C.-native. “It’s just an overwhelming feeling of excitement and hope.”

Fox does caution that a vaccine doesn’t mean the pandemic is over and that social distancing and wearing a mask will still be required for a period of time. But she says that she feels sort of like a Marvel character.

“I feel like I’ve been given a superpower.”

For Slocum, the last nine-plus months have been heartbreaking — but he was always hopeful this day would come.

“I’ve been down, but never lost hope,” says Slocum. “Discouraged, but always optimistic.”

This story was updated to reflect that United Medical Center is located in Southeast D.C.

Matt Blitz

Matt Blitz