Natalie Talis remembers the first COVID-19 vaccine clinic for health care workers in Alexandria. It was on Christmas Eve last year. Nurses in Santa hats and sparkly holiday garb applauded as they received their doses of the Moderna vaccine.

“There were tears,” says Talis, Alexandria’s population health manager. “After nearly a year of working so hard to try to prevent illness and stop the spread, to finally see this light at the end of the tunnel and to have it in hand really was kind of the best Christmas gift we could have given to people.”

Across the region, the vaccine rollout began with similar excitement and fanfare. In D.C., the first shot was given out on Dec. 14 to an emergency room nurse at George Washington University Hospital — with the then-Secretary of Health and Human Services, Surgeon General, and D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser looking on.

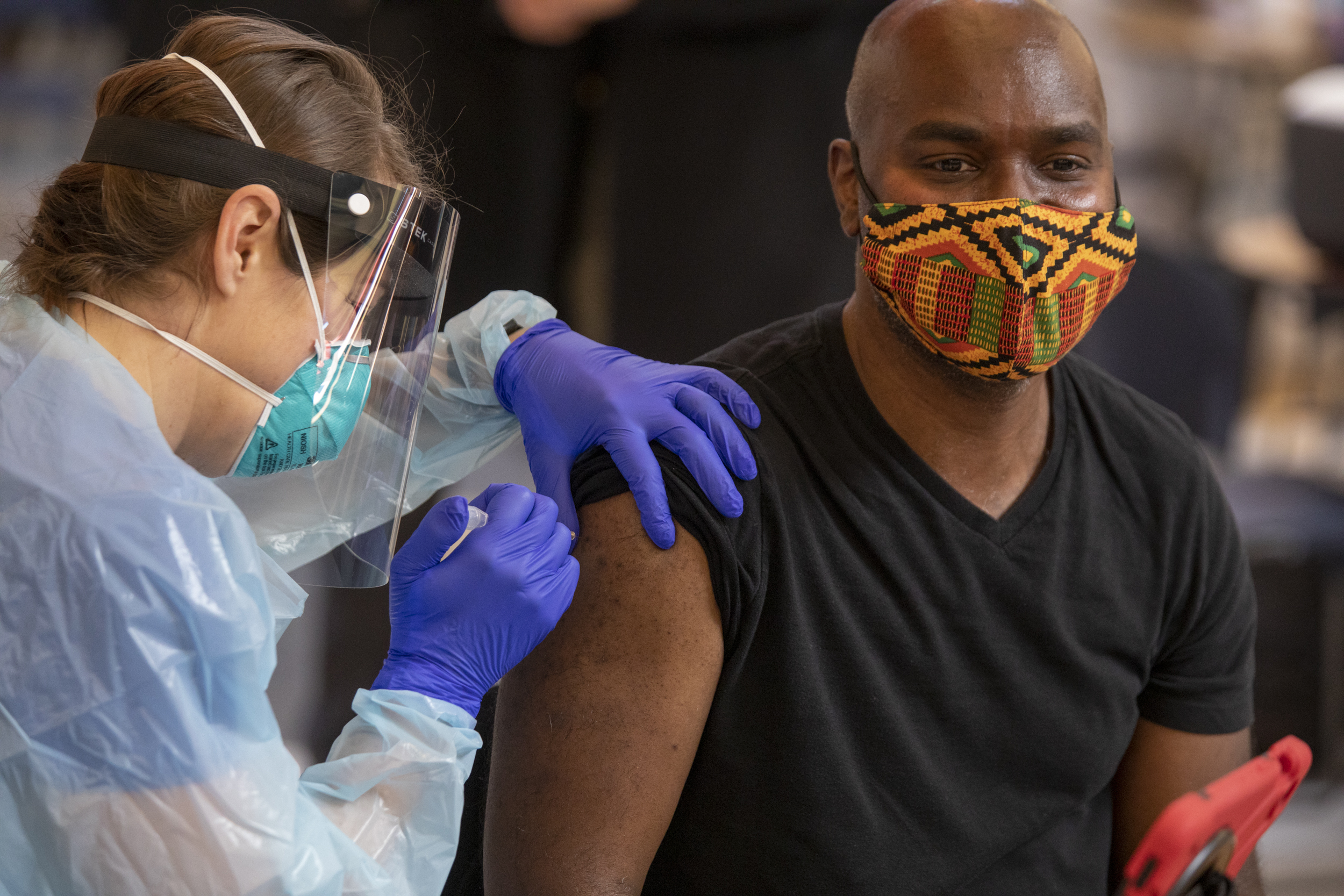

But, in January, as public health officials turned from vaccinating health care workers and first responders to lining up a slowly-expanding pool of people in the general public for shots, euphoria turned to confusion and frustration, borne of poor organization and a wild mismatch between demand for shots and the actual supply on hand. And that confusion bred access challenges and contributed to significant racial gaps in vaccination rates, which officials spent the rest of the year attempting to correct.

Today, the D.C. region has a high vaccination rate: roughly 65% in D.C., 65% in Virginia, and 68% in Maryland, in comparison to 60% nationally. But the second year of the vaccination campaign brings with it new challenges: a rush to get shots to school children 5 years and older, who became eligible in early November; the need to offer booster shots to people who are six months past their original course of the vaccine; the ongoing problem of convincing unvaccinated adults to get the shot; and a new winter surge in cases, with the presence of the omicron variant looming.

Local health officials and community leaders involved in the vaccine campaign are reflecting on what they’ve achieved (and not achieved) in the last year — sharing the lessons they learned along the way, and what role vaccines play as the region nearly wraps its second year of a pandemic.

Early logistical problems gave way to long-term equity challenges

The early days of the vaccine rollout, when seniors and people with serious medical conditions become eligible for shots, were chaotic. People scrambled to determine if they were eligible under different phases and subphases of complex official vaccine rollout plans. Complicated online registration portals crashed, repeatedly, and had to be replaced. States and localities struggled to coordinate registration systems — and to communicate with the federal government and its partnership with national pharmacy chains. Local health officials often didn’t know how many vaccine doses they were actually getting until shortly before they arrived from federal authorities.

In the chaos, many people who needed shots the most, like vulnerable older people and residents of color whose communities bore the brunt of the pandemic to begin with, were left behind.

Local officials, downstream from the state and federal authorities who were making most of the decisions about how and when to allocate vaccine doses, were mostly forced to react quickly, says Dr. Travis Gayles, who until recently served as Montgomery County’s health director. Early on, he says Montgomery County’s distribution was beleaguered by poor communication with the state over weekly dose allotments and supply.

“We literally did not know week to week how many doses we were going to get,” Gayles says. “We would literally find out like late Friday, or on the weekend, how many doses will be delivered for the next week…that created challenges because we couldn’t go to residents and say, ‘well, this is how many we’re going to get next week,’ or be able to be as transparent as possible.”

But as the winter wore into spring, the situation began to reverse: supply, instead of struggling to meet demand, began outstripping it. Now desperate to increase vaccination rates, localities started offering financial, edible, and even alcoholic incentives to draw in the unvaccinated.

By the summer, public health departments across the region had pivoted from gatekeeping who could get vaccines to attempting to convince people who hadn’t yet received a shot to get one, attempting to knock down the barriers to access for communities of color as much as possible.

But equity problems persisted, even as vaccine supply became more plentiful.

Chioma Iwuoha, a Ward 7 Advisory Neighborhood Commissioner and at-large committeewoman for the D.C. Democratic Party, points out that public health leaders were and still are fighting an uphill battle against longer-term trends in community disinvestment in Ward 7 and 8; while residents in other parts of the city could visit a number of nearby Safeway or Giant pharmacies for their vaccine appointment, residents east of the river didn’t have that option.

“We talk about the disparity in access to health access to vaccines here in Ward 7, simply because a lot of the sites that are used are grocery stores and the convenience stores. And east of the river, we don’t have that much,” Iwuoha says.

Local health officials have been criticized for not foreseeing and adequately correcting for racial disparities in vaccination. Talis says the problem wasn’t that public health officials weren’t aware of the likelihood of equity and access challenges — it was that they were overwhelmed by the chaos of the first few months of the rollout.

“Before the vaccines were even available in November and December, we had put together all of these plans for how we were going to do education and outreach and talk to people about vaccines and their importance,” Talis says. “But then it turned out, in December through April, that we couldn’t actually even implement those because we were so focused on just getting the vaccine into arms from the people who were kind of banging down our doors to get it.”

In many cases, attempting to correct for the stark inequities at the beginning of the rollout involved creating extensive community partnerships with social service organizations with deep ties in the community, and community leaders who could act as “trusted messengers” to share information and encourage people to get the shot. In the summer, Mayor Muriel Bowser launched a program sending community members door to door, partnering with local groups like the Anacostia Coordinating Council to promote vaccinations and help residents book appointments.

For community leaders at the center of the outreach effort, it was far from their first time helping connect local governments to underserved residents. Many have served, long before the pandemic, as the trusted messengers in communities that are already underserved by local health systems – building relationships and gaining the trust of residents that often go unreached by officials.

“It’s really hard for, let’s say, the Department of Health to come in and offer these services [vaccines] for free,” says Chris Charles, a health promotions manager at Latin American Youth Center (LAYC). “It’s like, ‘well why is this free?’ It’s almost a question of what is the motive behind it…especially when you look at wards 7 and 8 there’s not a whole lot of hospitals, or urgent cares, or places people can go to just get medication.”

Even before the vaccine was rolled out to the general public, Charles says LAYC was working to educate community members about COVID-19 by hosting informational symposiums in different languages. (For the first several weeks of D.C.’s vaccination rollout, the website to book appointments was only available in English.)

“There were a lot of times that people would mention, ‘it does mean something to have someone that looks like me, that can also break down the science, and not try to belittle me,” he says.

Montgomery County, which now boasts one of the highest vaccination rates in the country, worked with its Latino Health Initiative to create a public health ad campaign centered around “La Abuelina,” a Salvadoran grandmother cartoon character. The Latino Health Initiative also hired bilingual youth “trusted messengers” to help get people in their own neighborhoods vaccinated.

Gayles says reaching communities with low vaccine uptake necessitated addressing two separate issues, which at times were conflated and blamed for low vaccination rates: a lack of vaccine access and vaccine hesitancy.

“The first thing we did was we acknowledged that disparities in vaccine uptake aren’t entirely informed by [hesitancy], they are still significantly informed by access,” Gayles says. “Our approach immediately looked at, well, yes, there is hesitancy within communities. But how do we address the issue of having access for those people who are interested in getting it? Who wants to get it? How do we make sure that there’s fair, equitable access for everybody to be able to get into the system?”

Gradually, the slow and painstaking work began to pay off. Racial gaps in vaccination rates are generally narrower in the D.C. region than before. In predominantly Black Ward 8, 32% of the total population is fully vaccinated, compared to 54% in wealthier, whiter Ward 3. Nine months ago, the percentage of vaccinated seniors in Ward 3 was nearly double that of Ward 8.

In some cases, the gaps in vaccination rates disappeared entirely. In Virginia, for example,

65% of Latinos are vaccinated, compared to 57% of whites. In Maryland, white residents only outpace Latinx residents by one percentage point, and in Montgomery County, the “trusted messenger” initiative paid off: Latinx people are now vaccinated at higher rates than their white counterparts in the county.

The same is true in Alexandria. According to Talis, white people in the city now lag behind people of color in vaccination rates.

“We don’t have higher or lower rates by accident,” Talis says. “They happen because our bilingual teams and volunteers have spent hours and hours knocking thousands and thousands of doors and tabling in the community and the many hours of presentations to our community partners.”

Iwuoha, the D.C. ANC commissioner, is living proof that personal connections from trusted community members are powerful in persuading people to get vaccinated. Concerned by the long history of medical mistreatment of Black people by the medical establishment, and fresh off of her own bout of COVID-19, she delayed getting vaccinated until August — and when she did go in to get her shot, she didn’t tell her immediate family, who were also skeptical. But seeing her get vaccinated helped her family members ultimately decide to take the shot.

“I think [they all got vaccinated] primarily because I went ahead and did it,” Iwuoha says. “I do think that it’s helpful to have someone in your family to just take this leap of faith.”

What’s next?

During a call with members of the mayor’s team in late November, shortly after Bowser announced the end of the indoor mask mandate, At-Large Councilmember Robert White asked a question: “Are we still in a pandemic?”

Patrick Ashley, a senior deputy with DC Health, thought the councilmember was being sarcastic – but he wasn’t. He asked his question earnestly, after D.C. officials began encouraging residents to think about coronavirus in a new way – a way that’s less like a pandemic, and more like an endemic disease, similar to the flu. Part of this means that risk management and limiting exposure will become an increasingly individual choice and responsibility – and vaccination will be the most important part of that risk assessment.

“Dr. Nesbitt’s priority will continue to be vaccinating the unvaccinated,” says Heather Burris, the interim immunization division chief with DC Health. Despite the progress that’s been made, she says officials are still trying to cut through misinformation, a problem she described as one of the biggest hurdles left to overcome. Adults between ages 18 and 49 are the least vaccinated demographic in the city.

“The scary thing about that is [the 18 to 49-year-olds] are our parents, so one would assume, if the parents aren’t vaccinated, the kids won’t be vaccinated,” Burris says. “Focusing on families is going to be a challenge operationally, just because there’s so many different vaccine types right now, making sure our providers are equipped to be able to provide that family vaccinations so that parents and families aren’t traveling all over different points of the city, just to get everyone vaccinated.”

While cases, hospitalizations, and deaths remain much lower than when the vaccination campaign began, officials are now juggling efforts to reach individuals with first shots while encouraging boosters, all as a new variant emerges across the region. D.C., Maryland, and Virginia have all identified cases of the omicron variant, which early data suggests may be more transmissible than the already highly contagious delta variant. The omicron variant may also be able to evade antibodies – meaning it could infect those who already had COVID-19 or are vaccinated. It’s arrival comes as the region records an increase in hospitalizations and deaths following the Thanksgiving holiday – although a majority of them in unvaccinated individuals.

“I know a lot of people are coming out and getting their boosters now, we’re very happy to see that as well,” Sean O’Donnell, the emergency preparedness manager for Montgomery County said earlier this week. “But we want to continue having those dialogues with members of our community who haven’t gotten fully vaccinated, because that is one of the primary ways this is spreading.”

According to Talis, it’s unlikely that COVID will ever go away. But vaccines are at least one of the interventions that will stop the worst outcomes from arising.

“As we think about COVID long term, it really is thinking about, how do we minimize the effect of this disease on our lives? And part of that is through the vaccines, and making sure that we’re getting rid of some of COVID’s worst outcomes: the hospitalizations, the deaths,” Talis says.

Margaret Barthel

Margaret Barthel Colleen Grablick

Colleen Grablick