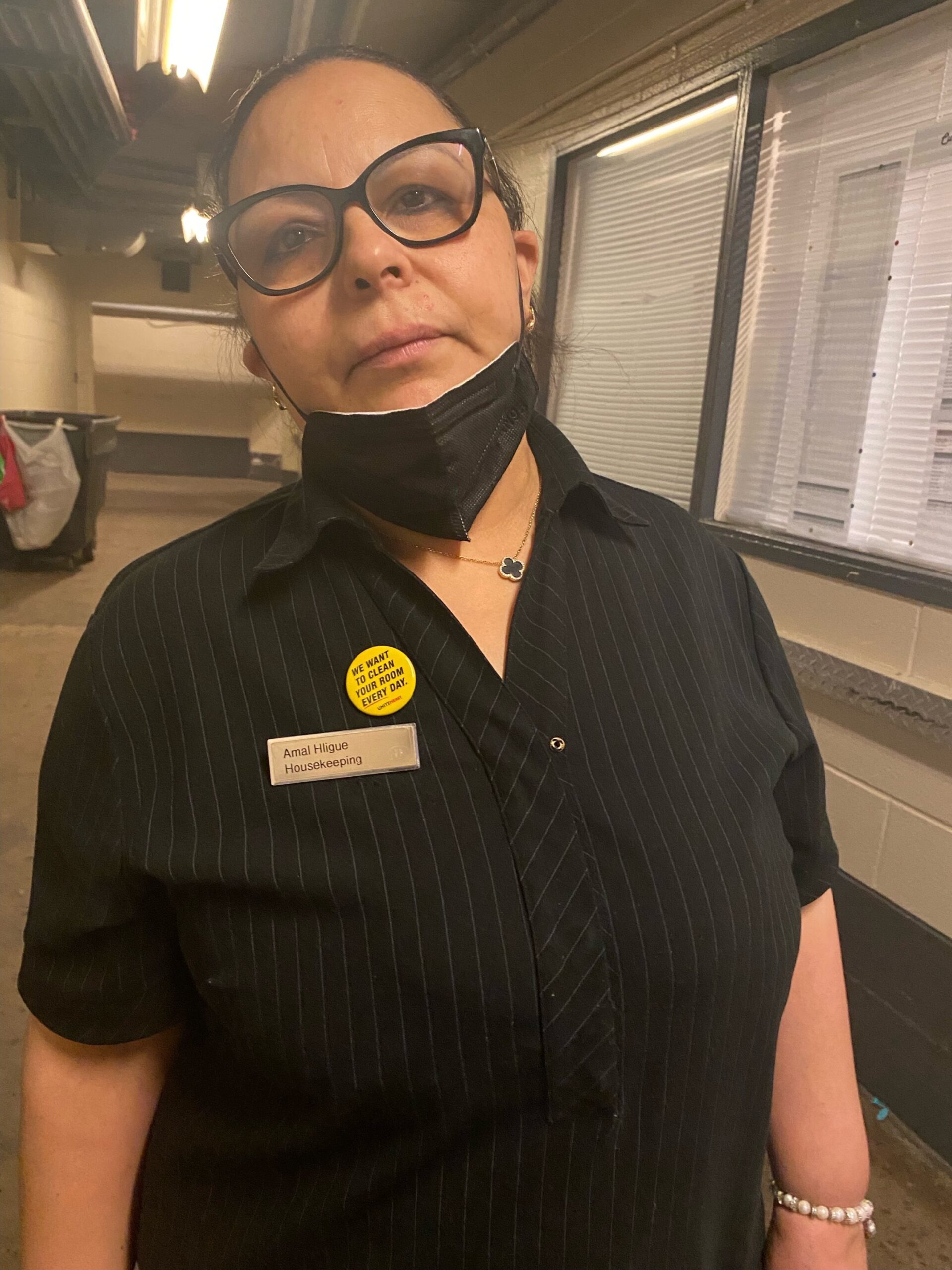

Amal Hligue has always covered her husband’s medical expenses. Unlike his job as a taxi driver, her employer — the Washington Hilton in Northwest D.C. — offers family health insurance.

That is, until recently.

Hligue is a housekeeper whose hours were cut back when the hotel’s business took a hit and room cleanings were reduced during the pandemic. These days, her work fluctuates dramatically: She says she recently went two weeks without any work at all, then last week she worked a full 40 hours. She managed to hit an average of 25 hours a week this quarter, the amount of time needed to become re-eligible for health insurance, according to her union UNITE HERE Local 25. She hasn’t, however, been scheduled the 30 hours that would qualify her for family insurance.

“He’s sick,” Hligue says across the street from the hotel after her 8-hour shift, one that was particularly taxing, she adds, because less regular cleaning means filth has accumulated over multiple days, making each room a heavier lift.

Her husband has high cholesterol and hasn’t been able to refill his medication for six months because it requires a doctor’s visit. Untreated, people with his condition can form blood clots, inducing a heart attack or stroke. But he can’t make an appointment until they find a way to pay for it.

Compared to her colleagues, Hligue, who’s worked at the Washington Hilton for 22 years, is one of the lucky ones.

Some 60 of the 100 unionized housekeepers at the Washington Hilton haven’t been called back to work after pandemic layoffs, according to Local 25, the labor union representing area hotel employees. Dozens more people in other departments also remain out of work. The union’s chief of staff, Paul Schwalb, says countless housekeepers across the D.C. region are still laid off, largely because many hotels have not returned to the pre-pandemic standard of automatic, daily room cleanings. He suspects that non-union hotels, which account for the vast majority of the region’s almost 700 hotels, have fared worse when it comes to job losses. According to the union, those out of work are disproportionately women of color and immigrants.

In an attempt to protect laid-off workers, D.C. lawmakers passed an act requiring large hotels, among other employers, to first offer newly-available jobs to the workers they let go of during the pandemic. The union says some hotels have circumvented the law by reclassifying workers (like having the front desk handle guests’ bags instead of the bellhop) or cutting services altogether.

“For them to come out of the pandemic and try to do away with jobs as opposed to grow jobs is something that they should honestly be ashamed of,” Schwalb says of the Washington Hilton.

Every hotel Local 25 bargains with except the Washington Hilton agreed to continue to service rooms daily, unless a guest declines. The union represents just under 40 of the nearly 700 regional hotels.

The Hilton changed its housekeeping policy at most properties in the Americas when they reopened from pandemic closures, according to the global hospitality company’s website. A Hilton spokesperson says the company aspires to offer guests “choice and control of the housekeeping services.”

The national spokesperson did not comment on Washington Hilton specifically, however, and they did not respond to an interview request by the time of publication. Individual hotels set staffing levels and scheduling, which are partly informed by market demand, she adds.

Schwalb is skeptical of the Hilton’s argument, saying that the multi-billion-dollar, multinational company changed its housekeeping policy to reduce labor costs, not to better accommodate guests. “They’re telling their investors that they’re taking away their daily room cleaning because it grows their profits,” he said.

A 2022 poll conducted by Morning Consult and commissioned by the American Hotel & Lodging Association (AHLA) found that 31% of guests preferred a daily room clean, while 38% preferred a clean only when requested, and just 19% preferred that housekeeping only occur at the end of a stay.

The pandemic hit the hospitality industry especially hard, and hotels have yet to fully recover. According to the D.C. Office of the Chief Financial Officer, the hotel occupancy rate historically averages around 70% but was just 48.3% in November. In a federal financial filing from February, Hilton Worldwide Holdings Inc. said that the pandemic continues to negatively impact the hospitality company.

Hotel occupancy in the District is improving — there were 197.4% more rooms sold in November as compared to a year ago, according to the D.C. CFO. But at the Washington Hilton, business returning does not yet seem to signal good news for out-of-work housekeepers.

Emebet Samuel-Kassa, a Local 25 organizer who represents Washington Hilton employees, says despite having 879 occupied rooms one Monday in March, they only had 23 housekeepers working — half of the number that used to be scheduled.

“There are a lot of rooms that are occupied that can be cleaned,” she says. “At the end of the day, we know that they’re saving money by not scheduling room attendants.”

Many of the workers who still work full time say that eliminating daily cleanings makes their jobs more difficult. Lucy Biswas, who’s been a housekeeper at the Washington Hilton for 48 years, says it used to take her 30 minutes to clean one room but now it can take up to an hour. “For us, it’s unfair,” says Biswas, adding that she and her colleagues can’t keep up with the quota of 12 rooms per 8-hour shift when many are only being cleaned at checkout, after a guest has occupied them for 3-to-6 days.

These jobs were already back-breaking: Hotel housekeepers suffer some of the highest injury rates among service-industry workers, according to a recent U.S. Department of Labor survey.

Biswas is nearing retirement age, so she tires more easily than before. The heavy-lifting can require everything from pushing a 70-pound cart to lifting a 100-pound mattress. Biswas’ back hurts sometimes. She’s frustrated knowing that while she’s overburdened, her laid off colleagues could really use the work.

“We’re doing our best,” says Biswas. “We wish we [could] work every day and for them to call more people — more team members — because it’s hard for them.”

Some housekeepers have applied to other jobs to make up for lost hours. Aynalem Yigletu, a supervisor and housekeeper at Washington Hilton, worked a seasonal job at Macy’s. But well-paid, union jobs are hard to come by: Washington Hilton pays $24 per hour, above the average hourly rate for housekeepers in the area.

“If you don’t pay your rent, if you don’t pay your bills, we don’t pay our car’s bill, maybe the car company comes to take it. The house, maybe we’re going to [be] kicked out. It affects a lot,” she says. “Sometimes I feel like cry[ing] because there is nothing I can do about it. I go to Subway. I go to Starbucks sometimes. I say ‘Do you have [an] opening?’ they say, ‘We’ll call you. Leave your number.’ Nobody calls you.”

Larry Yu, a professor of hospitality management and tourism studies at George Washington University, says some hotels had scaled back housekeeping prior to the pandemic for environmental reasons. Media reports show that while the practice of eliminating daily room cleaning may be unique in D.C., it’s becoming a more widespread practice nationally and potentially costing over 180,000 jobs. Ultimately, Yu says the ethos of the hospitality industry means hotel management should compromise with their workers.

“You take care of your employees and they will take care of your guests,” says Yu.

Meanwhile, many workers are in limbo. Workers like Hligue who aren’t scheduled enough hours are still holding out hope. Washington Hilton was Hligue’s first job when she immigrated to the United States decades ago from Morocco.

“I like it. It’s nice,” she says of her housekeeping job. When she’s full-time, it’s one of the best-paying jobs available to her. “Everybody knows you — management knows you. Staff. Everybody.”

Every Thursday for the foreseeable future, she anxiously awaits her schedule, hoping to work enough so her husband can access health care.

Amanda Michelle Gomez

Amanda Michelle Gomez