Monica Goldson sat in her office, weighing the options.

In December, as the omicron variant of the coronavirus propelled infections to record levels, the chief executive officer of Prince George’s County Public Schools confronted her latest dilemma in an academic year full of them: keep schools open, or temporarily shift instruction online?

No other school system in the Washington region had decided to close buildings district-wide. But as Goldson considered how she could keep families safe and slow the virus’ spread without disrupting learning, she made a decision.

“The only way was to pull the trigger on virtual,” she recalled in an interview.

The call was not a popular one at the time, Goldson admitted. But she says the decision to temporarily shift the 131,000-student school system to virtual learning the week before winter break and for two weeks after likely shielded students and staff from the worst of the outbreak: while schools elsewhere in the region dealt with widespread quarantines and, in some instances, building closures triggered by ballooning case numbers, students and educators in Prince George’s County simply stayed home.

It was not the only time Goldson chose a more cautious route than superintendents and school boards elsewhere.

Prince George’s was the last public school system in the Washington region to offer in-person learning options to students in the 2020-21 academic year. Thousands of elementary students spent the first half of this year learning virtually. And the Maryland school system is still requiring masks, even as neighboring districts have dropped their mandates.

“I am very cognizant of what’s happening in surrounding areas,” Goldson said. “It doesn’t impact the decisions I make because I solely have to look at just Prince George’s. Other districts, early on, their COVID numbers were just not as high as ours.”

The majority-Black county was scarred by illness and death in the first months of the pandemic, creating fear around in-person school. Families and educators say the careful strategy around running in-person school has built trust in the district , helping avoid clashes over in-person learning and masking that have divided other communities.

“Because Prince George’s was hit so hard, our community has really embraced this conservative approach,” said Donna Christy, president of the Prince George’s County Education Association, a union that represents more than 10,000 educators. “I think we made the best of a really bad situation.”

Ernest Carter, the health officer for the Prince George’s County Health Department, credited the county’s cautious approach during the pandemic with helping curb death and hospitalization rates over time.

“We are a little bit more conservative. We’re very mindful of our population and its characteristics,” Carter said. “Our residents are mindful too. They are very aware of the situation that we were in … and how we got out of it.”

‘It was just very hard to see’

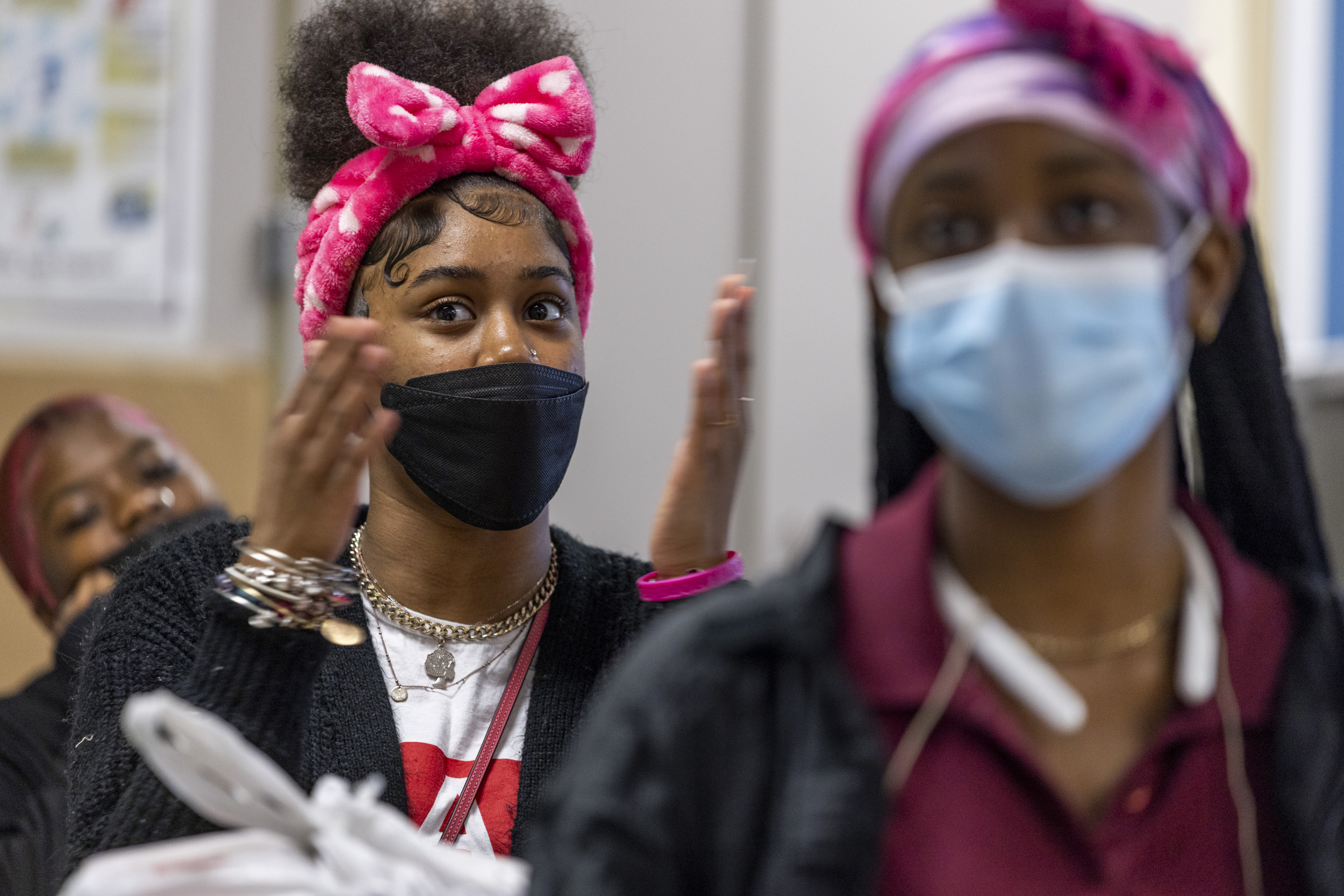

On a recent morning at Frederick Douglass High School in Upper Marlboro, a group of about 20 students in a social issues class broke into a lively discussion about the dangers of global warming and advocating for change.

Jaylyn Hewitt, a spirited 16-year-old in a Star Wars sweatshirt, stopped to make a point about burnout.

“While we’re focusing on climate change, while we’re focusing on homelessness, while we’re focusing on racism, we also need to be focusing on our own health and bettering the way we view life as a whole,” Hewitt said as her classmates erupted into cheers and applause.

Hewitt was speaking from personal experience.

During the pandemic, the teenager said she consoled one friend whose grandmother died after contracting the coronavirus. Other friends had to move away because their families lost jobs during the pandemic and could no longer afford to live in Prince George’s, one of the most affluent majority-Black counties in the country.

“It was a whole bunch of people who would come to me and tell me about their problems,” Hewitt said in an interview after class. “It was just very hard to see. Ninth grade – I was happy. We were all doing good. And to just see that collapse in the pandemic, it was just hard.”

That “collapse” was evident at campuses across the school system – students struggled to cope with fear and grief as their communities were devastated by the worst effects of the virus, educators said.

Prince George’s, the second-most populous jurisdiction in Maryland, has recorded the highest number of COVID-19 cases in the state, surpassing its larger neighbor, Montgomery County. Longstanding racial and health inequities played out here as they had across the country: Black and Latino residents suffered a disproportionate impact from the virus, becoming sick more often and getting sicker when they did.

That led to significant consequences for a school system where the majority of students are Black and Latino. Many students had grandparents or parents who contracted the virus, educators say, leading to hospitalizations and some deaths.

“You would have students emailing you weekly being like, ‘I can’t attend virtual learning because I’m going to this funeral,’” said Erin McCarty, a history teacher at Frederick Douglass who teaches the social issues class.

Some of McCarty’s strongest students stopped completing assignments, she said. Conducting classes virtually felt like a “seance” – the teacher found herself calling out students’ names to make sure they were following along with their cameras turned off.

Families shared obituaries of loved ones with the school, said Principal Eddie Scott. One father who was hospitalized in an intensive care unit after contracting the coronavirus told the principal his daughter was “not in a position to learn” because she faced significant anxiety over the situation.

Sixty-five students are repeating ninth grade this year because they did not earn enough credits last year to advance to tenth grade, which is about three times as many students in a typical year.

Students returned for in-person learning in August with post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety. Teenagers experienced panic attacks in classrooms, according to Miaela Thomas, a counselor Frederick Douglass hired at the start of the school year.

Teenagers cannot be expected to perform academically if they are struggling with mental health, Thomas said. So she established a hotline where students can reach her during and after school to talk or schedule wellness visits.

More than 100 texts have arrived since the start of the year, including one from a student who attempted to take her life.

“Had we not known through this text message system, it could have been bad. She knew who to reach out to, she knew who to contact to get help,” Thomas recalled.

So even as vaccines have become widely available and death and hospitalization rates have declined, Scott said families at Frederick Douglass remain cautious about the pandemic and support mitigation measures such as the mask requirement.

“People in our community don’t want to relive that kind of experience,” he said.

Teenagers readily comply with the mask requirement. Teachers distribute bottled water in class because fountains are shut off. And during the omicron surge this winter, parents peppered school administrators with questions about their plans for keeping students safe.

Eleventh grader Isaiah Butler said he still limits interactions with people he does not know for fear of contracting the virus. Butler watched his younger sister become sick with COVID-19 at the start of the pandemic.

“She was nauseous like all the time. Headaches. Stomachaches for about two weeks,” the teenager recalled. “When you see people go through it and when you live through it, it really does do something to you.”

Addressing loss

Throughout the pandemic groups including the American Academy of Pediatrics, a leading physicians group, have stressed the academic and social benefits of in-person learning.

Still, about 12,000 students in kindergarten through sixth grade in Prince George’s decided to learn online for the first two quarters of the 2021-2022 academic year. That made the county an outlier in the Washington region – most other local school systems educated far fewer students online, limiting virtual instruction to students with qualifying health conditions or other extenuating circumstances.

Leading up to the school year, Goldson said she was inundated with messages from parents of young children who did not feel comfortable sending their children back to in-person school before they became eligible for a vaccine.

“My soul wasn’t settled. I could sense the anxiety for parents,” she said. “And I put myself in their shoes – if I had a child that age, what would make me feel comfortable?”

In Maryland, results on standardized tests administered this spring will provide the fullest picture of where students stand academically since the public health crisis began.

The state waived the annual tests in 2020 because of the pandemic, and administered an abbreviated version of the exams known as the Maryland Comprehensive Assessment Program in the fall of 2021.

Scores on those tests, which state leaders said were only intended to provide a snapshot of the pandemic’s effects on learning, showed steep declines in student performance on math and English exams.

In Prince George’s, results on those tests painted clear challenges: for example, 13 percent of students in third grade demonstrated proficiency in reading and 5 percent or less of students were proficient in math.

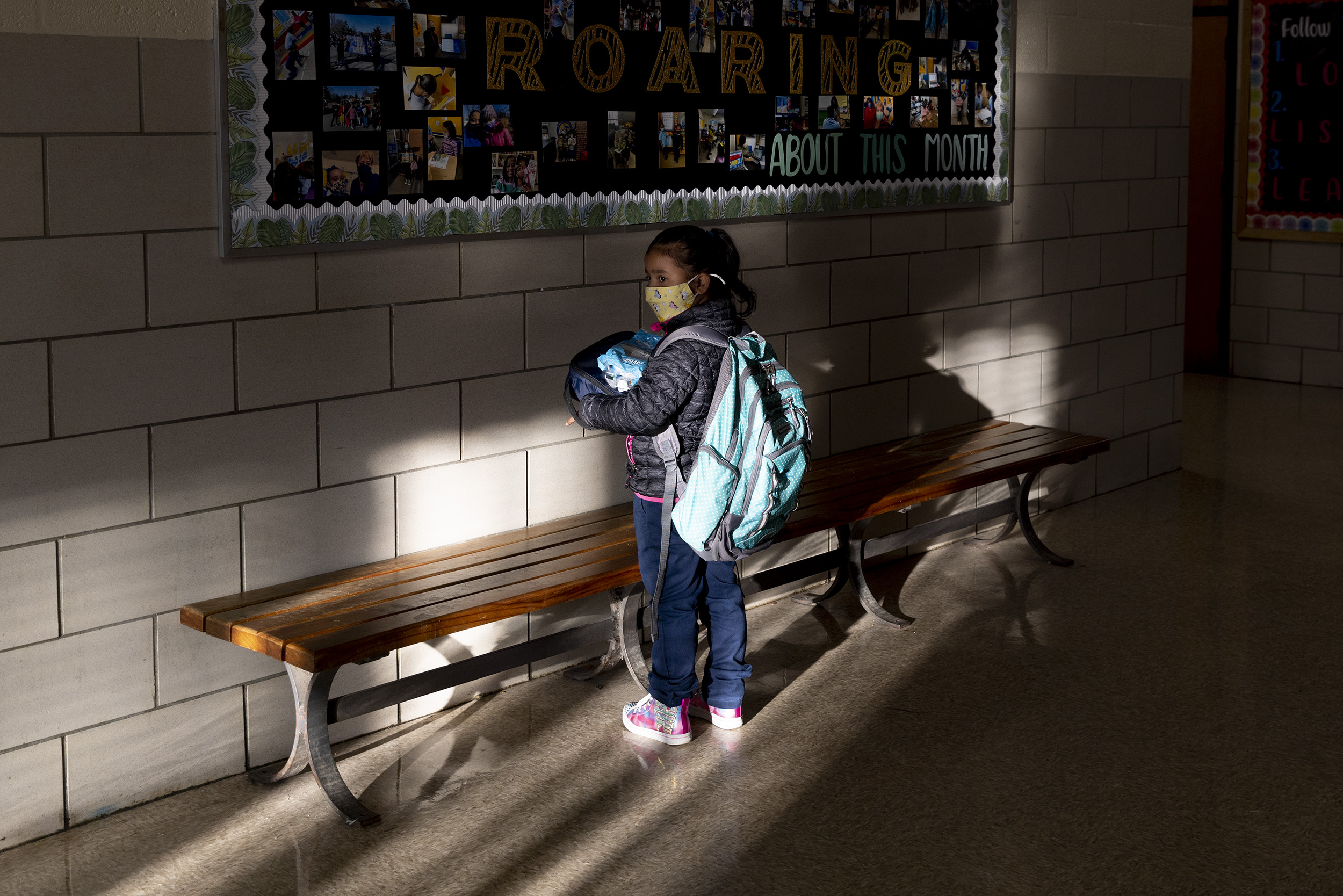

At Princeton Elementary School in Camp Springs, educators say they do not need test results to understand that students are struggling academically.

Even before the pandemic, students at Princeton did not perform well on state tests. In 2019, fewer than 18% of students were considered proficient in math and reading, respectively.

Principal Jessica Coley said online instruction was no match for face to face interactions with teachers.

“We know that there’s learning loss,” she said. “No ifs, ands, or buts about it. We see it in the way in which students are performing.”

Some teachers instructed children concurrently, with some students learning in person and others logging on from home. The school system paid teachers up to $7,500 extra if they taught in person and virtually at the same time.

Douglas Hernandez, who teaches English as a second language, said 11 of the 12 children in his kindergarten class stayed virtual for the first half of the year. In first grade, 13 students in a class of 19 learned remotely.

Children who attended his class in person have performed better than those who started the year virtually. Those who logged on to class struggled heavily with writing, he noticed. The teacher spent class asking students to point their paper toward computer screens so he could read words they wrote, reminding them to capitalize letters at the start of each sentence.

“They had learned that but they were forgetting. They were not practicing,” Hernandez said. “I had to be on them a lot.”

Many immigrant parents knew their children were not performing well online, but viewed virtual learning as a way to protect their families, Hernandez said. A majority of English learners at Princeton speak Spanish as their first language. Others speak Urdu and Tagalog.

“They have lost family here and in their [home] countries [to COVID],” Hernandez said. “Many people died, grandpas, uncles, cousins.”

When the school system ended the virtual option for elementary school students in January, some parents hesitated to send their children back to Princeton. Those families were not alone – a countywide petition urging Goldson to maintain the virtual option until the end of the academic year garnered more than 1,670 signatures.

The school system’s mask mandate has also created some challenges for teachers, but educators and parents still say the benefits of gaining community trust and making families feel safe are worth it.

Cama Kalee Wilson, the lead reading instructor at Princeton, wears a KN95 mask every day. But the face covering muffles her voice, making it harder for young students to distinguish between similar sounds such as “ba” and “pa.”

So Wilson purchased a portable speaker and microphone, carrying it as she teaches to amplify her voice. She still supports the school system’s mask mandate.

“We’re still in a pandemic,” she said.

Jennifer Jones, whose son attends Princeton, said she has taken more risks than other parents during the pandemic when it comes to her child’s education. She enrolled her son in daycare when an in-person option for preschool was not available because she felt it was crucial for his development.

But Jones said she does not begrudge the school system for taking a cautious approach to running campuses during the public health crisis. She does not understand how other parents could force their demands on school leaders.

“Honestly they’re doing the best they can,” said Jones, who teaches physical education at Princeton. “It’s like sometimes people are so entitled and they want everything the way they want it instead of thinking of the greater good.”

Nearly 20 miles away at Mount Rainier Elementary School, Timothy Meyer, the president of the school’s parent-teacher organization, said some parents in the community wanted the school system to return to full in-person learning for all students sooner.

About 40 students started the year virtually, Meyer said, but many of those families decided to send their children back in person within a few weeks of the start of the school year.

For the most part Meyer said the school system has avoided charged confrontations over reopening that have unfolded elsewhere in the Washington region.

In the District, the Washington Teachers’ Union and school system officials repeatedly clashed over when and how to reopen buildings. In Fairfax and Arlington counties, parent groups formed to pressure leaders into opening schools. And in Northern Virginia, the battle over masking polarized some communities.

“We don’t have parents at school board meetings shouting about kids being unmasked and things like that,” he said. “The way that I’ve tried to approach this is – if you have to choose between a little bit of inconvenience or people possibly losing their lives, you need to take the inconvenience every time.”

Back at Princeton, Coley, the principal, still believes the caution around running schools in the county has been necessary, even if it meant many of her students spent 20 months outside of a physical classroom.

She understands firsthand the anxiety in her school community. Coley’s father was diagnosed with cancer in July 2020. Before he died, she feared infecting him with the virus and making him sicker.

“It has been hard to lead when there is such a significant absence in my life,” she said. “But I’m able to relate with many of my families.”

Moving forward, Coley is optimistic. With all students back in person, administrators and school leaders are now working to identify students who need extra support.

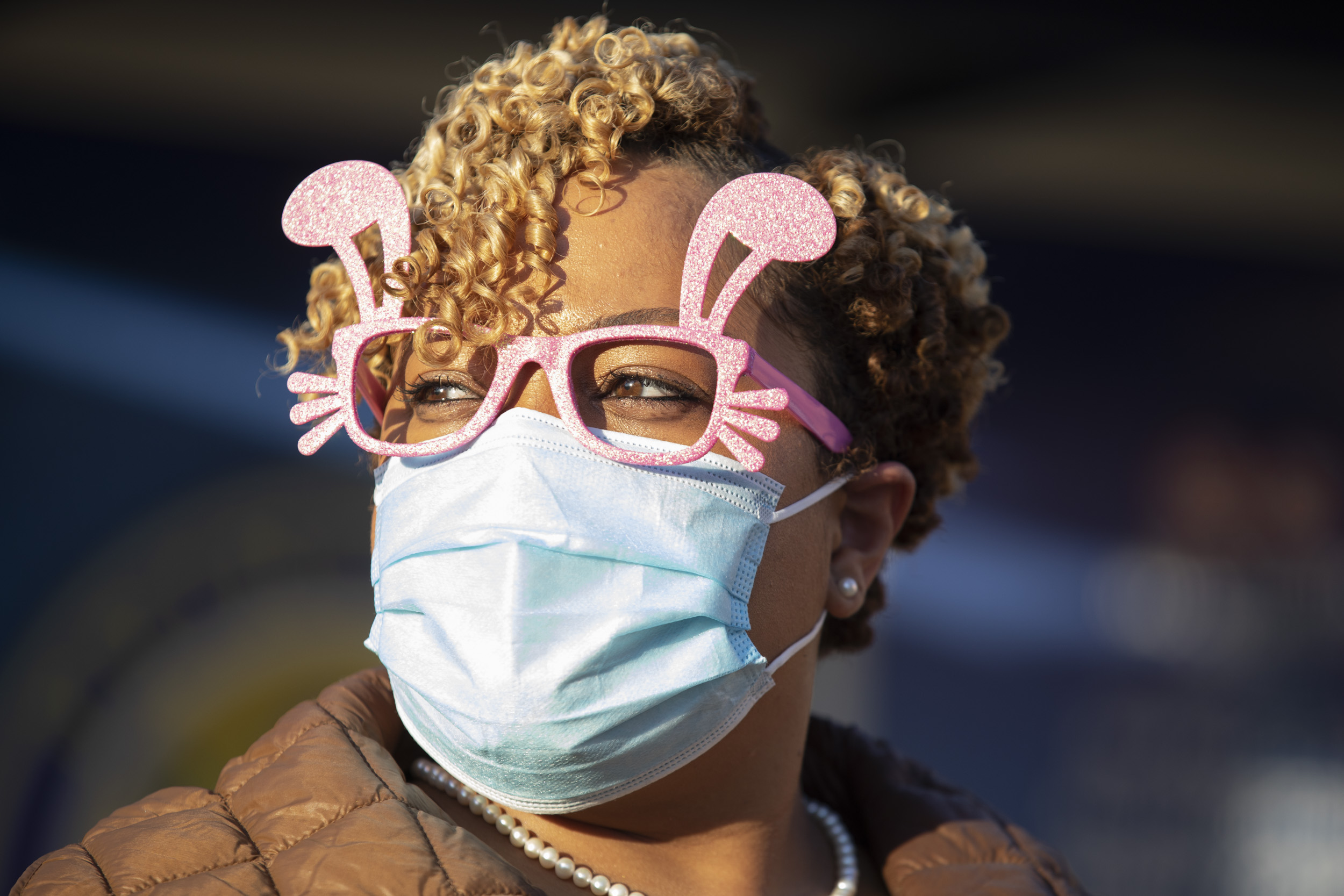

On the day before spring break, Coley stood outside the school as children arrived, welcoming them in pink bunny glasses and wishing them a Happy Easter. She doled out elbow bumps as children hustled into the building.

She directed one girl who arrived without a face mask to another school worker, who supplied a disposable pink mask with cartoon pandas printed on it.

“It will take us some time to get through this,” Coley said. “But I’m hopeful.”

Debbie Truong

Debbie Truong