The D.C. region is experiencing its first substantial uptick in coronavirus transmission in several months.

But this time, things look different – both in how the public responds to transmission, and how we can measure it. Unlike during previous surges, when we were sometimes able to chart spikes day-by-day, transmission is now largely measured by other metrics, namely hospitalizations over time. Regionally, a bump in hospitalizations due to COVID-19 started in July; by the end of the month, the number of COVID hospitalizations in D.C. had increased 30% from the month prior, according to CDC data. (Data for August is not yet available.)

In Maryland, the rate of new weekly COVID hospitalizations per 100,000 residents rose from 1.08 on July 1 to 2.10 on July 29. According to the state’s data, a total of 125 people were currently hospitalized with COVID as of Aug. 7, up from 57 on July 1. Meanwhile, in Virginia, 146 people were admitted to the hospital with COVID in the last week of July, a slight increase from 121 in the last week of June.

Although the current rates indicate an increase in viral transmission, hospitalizations still remain low relative to the most recent spike, which occurred in January this year, and significantly below what we saw during our most deadly surges, like the winter omicron peak in late 2021 and early 2022.

“We’re probably not in the same sort of surge as our winter omicron surges have been,” says Neil Sehgal, a public health professor at the University of Maryland and the University of Washington. “I think what it is, is, unfortunately, a sign that we have a lot of potential for more explosive growth as we move from summer into fall.”

As has been the case for the past three-plus years, it’s difficult to pin down precise causes of the current uptick. It’s likely the result of the usual summer-time factors: increased travel and socialization. Sehgal suggests waning immunity – both from previous infection and vaccines – could also be at play, as a new omicron subvariant, EG.5, takes hold. All of the variants circulating right now are of the omicron lineage (as one public health professor told the Washington Post, EG.5 is like one of “several Barbies in the same film.”) Like other omicron subvariants, EG.5 has shown to be better at evading immunity protection, but it isn’t making people sicker.

Further complicating the understanding of the current surge is the shift both in the public perception of COVID in the past year – and the way the virus is tracked.

Public health departments – including locally and at the federal level – have stopped tracking regular case data, as its significance fell with the ubiquity of at-home tests which often went unreported. In what Sehgal calls the “post-case data” era, we’re left to rely on hospitalization metrics, as well as emergency room visits and deaths to track the trajectory of spread.

“One of the challenges is, with the landscape of data that’s available to us today, we’re only really able to tell that we’re in a surge sort of in retrospect,” Sehgal says. “How nice was it back when we had smooth curves of case data, and we could make decisions in our lives based on that?”

Analysis of wastewater is a helpful tool for spotting increased transmission early, but our region has not yet built out a robust wastewater reporting system. Zero of D.C.’s nine sampling sites have current data to report, per the CDC. (The city’s wastewater surveillance program was originally beset by delays, and officials told DCist/WAMU last year that surveillance would phase out when case rates stabilized at a low level.)

Across Maryland, only seven wastewater sites are providing current data to the CDC, and four of them indicate an increase in the presence of COVID over the past 15 days. Neither Montgomery County nor Prince George’s County have reportable data. And in Virginia, five sites are reporting an increase in transmission, although none of them are located in the region. (Fairfax County, Arlington County, and Alexandria sites did not have current data as of Aug. 11)

In lieu of dashboards and rising and falling lines on a graph, Sehgal says that relying on anecdotal evidence is one of our best bets (though, of course, it doesn’t beat sound public health data).

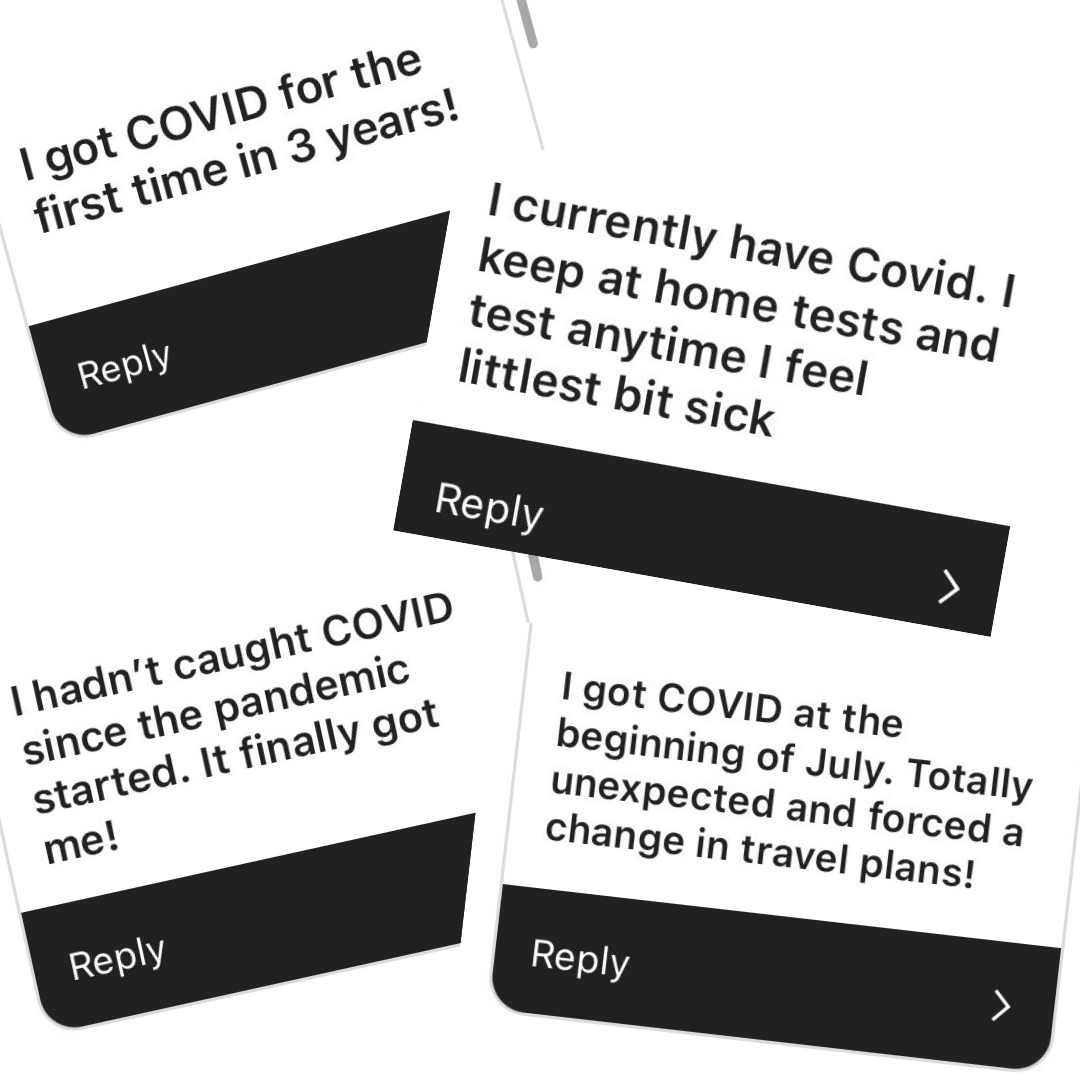

When it becomes a situation where “everyone knows someone (who knows someone) who has COVID right now,” it’s safe to say it’s not a coincidence, but part of a trend – and a useful data point to use to gauge your risk.

“Certainly, I can count more recent infections since July 1 than in the previous three months, or maybe even the previous six months among my social circle,” Sehgal says.

We asked DCist/WAMU readers how they were managing the current uptick, and responses ranged – underscoring the varying degrees to which people do or do not think to protect against COVID anymore. One person said they “had no idea” transmission was up. Several people said they had COVID right now – and many for the first time. One mentioned a work conference that became a superspreader event, while another mentioned a close call at their child’s daycare.

With free tests no longer available at the library or COVID Centers in D.C., and no current plans from Joe Biden’s administration to ship tests directly again, testing is now less convenient and harder to come by. Rapid tests can be purchased at pharmacies like CVS and Walgreens, but they tend to go for $10-$12 a pop, likely changing the calculus on how frequently you want to test — especially when it can take days for a positive result to show up. (When omicron first came on the scene in late 2021 and early 2022, researchers detected that rapid tests were less likely to detect infection early on, even while symptomatic.)

As for more-accurate PCRs, those can be obtained at a doctor’s office for a price, and at some CVS clinics, but will likely require a copay; since the federal government ended the public health emergency in May, insurance providers are no longer required to waive costs or provide free testing.

“If you’re not savvy about using your insurance, or if you’re not insured, then PCR testing has become prohibitively expensive,” Sehgal says. “Because it’s no longer viewed as a public good protective measure.”

People may be testing less, or mistaking a COVID infection for a “summer flu,” allowing transmission to continue undetected. And while vaccines still afford protection against serious illness, as the region heads into back-to-school season (and the weather turns cooler) Sehgal expects the bump in transmission to continue. He says this is a risk to both immunocompromised or elderly residents, who are most vulnerable to severe illness from COVID, as well as otherwise healthy people who may go on to develop long COVID.

“It’s been out of mind for people who aren’t experiencing [long COVID] and debilitation for people who do,” Sehgal says. “There’s still a risk with every infection, that the symptoms you experience will last. And certainly, it’s not cognitively comfortable to think about, but the risk of long-term COVID symptoms has not gone away.”

Another booster vaccine should be on the way by the end of September, this time specifically formulated to target the XBB.1.5 variant. But Sehgal says if the uptake of the last booster tells us anything, it’s not likely this will have much of an impact on community transmission. In D.C., less than a third of people who got at least one dose of a COVID vaccine received the bivalent booster. In Maryland, 26% of residents are up-to-date on their vaccines, and in Virginia, 23%.

“It’s challenging for me to believe that we’ll see a significant dent from the availability of that booster,” Sehgal says. “Of course, people who are medically vulnerable, elderly or immunocompromised are more likely to get vaccinated, and so there will certainly be a benefit in protecting people who are more medically vulnerable. But certainly, we’re not going to see the total potential benefit of that updated fall vaccine.”

Colleen Grablick

Colleen Grablick