“Has anyone heard what Narcan is?”

Safwaan Islam, with the Alexandria Health Department, poses this question to the staff at Virtue Feed & Grain. A few hands go up.

Employees at the Old Town restaurant are learning how to use the naloxone nasal spray, which reverses opioid overdoses. Shortly after the FDA made Narcan available over-the-counter, Alexandria’s Health Department and Department of Community and Human Services announced they would start offering training and boxes of Narcan to restaurants. The city is aiming to train staff at 25% of restaurants, cafes, and bars by the end of this year.

Virtue Feed & Grain is among the first to participate. So far, the restaurant has been “insulated” from the crisis, owner William Smith says. But he believes it’s “only a matter of time.”

“This program today helps us be prepared for that day, when it does come,” Smith says.

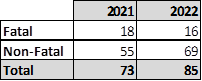

In recent years, Alexandria has seen an upswing in opioid overdoses, mirroring national trends. The COVID-19 pandemic seemed to mark a turning point. In 2020, for the first time since it started tracking this information in 2017, the Alexandria Police Department recorded more than 100 total overdoses. While reported overdoses have gone down since then, fatal overdoses in the last two years (18 in 2021, and 16 in 2022) were about twice what they were in 2017 and 2018.

As of July, there have been 42 overdoses this year, four of which were fatal, the police department told DCist/WAMU. (A spokesperson noted that the overall number of overdoses may be undercounted, because APD only counts overdoses of people who are sent to the hospital).

The restaurant’s manager, Marie Ackerman, grabs a couple of doses after the training. She’s impressed by how simple Narcan is. She thought it would be something more daunting, like a needle. But it’s just a nasal spray, with no dangerous side effects. And in Alexandria, it’s free.

“Anybody can do it. I think even a child can do it,” Ackerman says.

It was a child who discovered a man overdosing in the restroom at a restaurant Ackerman used to work at years ago. “That was very concerning and very scary,” she says.

Islam says the health department is targeting restaurants because it has existing partnerships with them: the department already performs routine inspections and permits all food establishments in Alexandria. His co-trainer, Amanda Coletti, is the health inspector for Virtue Feed & Grain. There have been similar partnerships with bars and eateries across the country.

Training restaurants is just one part of a larger strategy. Alexandria released a three-year plan earlier this year that also names taxi drivers, hospitals, high opioid providers, and large housing complexes as partners to receive training on Narcan and opioid overdoses.

Despite the ongoing opioid crisis, it’s clear that some of Virtue Feed & Grain’s staff aren’t used to talking about overdoses and harm reduction. There’s a bit of commotion when one of the employees asks Islam and Coletti a series of questions.

“Test strips, how available are they for the public?” the employee asks.

Islam explains that fentanyl test strips are available with the health department and are becoming increasingly accessible in other D.C. area jurisdictions. (Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid up to 100 times more potent than morphine that is increasingly laced with both opioid and non-opioid drugs and has been linked to a majority of overdose deaths in recent years.)

“So you can test your own drugs if needed,” he tells the employee. “That’s not a bad idea.”

When the employee asks whether Narcan is free, some of the staff start laughing.

“No, these are great questions! Do not laugh at him,” Islam tells the staff. “This is the whole issue we’re trying to break down. We want to encourage people to reduce harm.”

For the workers – and ostensibly the trainers – it’s a lighthearted moment; and the employee pretends to leave the room in embarrassment.

But Coletti says the moment reflects a mindset that she and Islam are trying to challenge.

“It is good to laugh and I know they’re friends, but also that’s part of the whole stigma,” Coletti says. “We don’t want people to have to just laugh at it. We want them to also take it seriously … the gentleman had asked a really good question and I’m glad we were able to answer it for him.”

Coletti says overcoming stigma is key to fighting the opioid crisis. She and Islam hope that making Narcan more available will help people become more used to talking about it and harm reduction strategies.

They also want to challenge preconceived notions about who might need Narcan. They stress over and over: “it could be anyone.”

“It could be the CEO of a Fortune 500 company. It could be an owner of a restaurant. It could be someone who’s homeless out there. It could be a student,” Islam tells the Virtue Feed & Grain staff.

Overdoses used to happen primarily among men in their 20s to 40s, according to the Alexandria Police Department. But since last year, the department says there’s been a significant increase in overdoses among minors who take counterfeit Percocet, laced with “suspected fentanyl.” Ackerman’s husband, a priest, has performed funerals for overdose victims — some of whom were very young.

Coletti says most restaurant owners her team has approached don’t know what Narcan is. Those with school-age children, however, tend to be “very aware” and more receptive to getting Narcan-trained.

But it’s not always easy to get restaurants to participate.

“When I explain it … they’re kind of hesitant,” she says. “Because they’re like, ‘oh this is a drug for opioids,’ and that’s where the whole stigma plays into it.”

Coletti and Islam would then try to talk through the benefits of getting trained, and how “you never know who you can save.”

“That definitely gets them a little more into it,” she says. But there are still some restaurant owners who are resistant. She’s hoping that as the program grows, more establishments will follow.

Tom Gale, director of operations at Virtue Feed & Grain, says participating in the program is part of the restaurant’s mission to serve people.

“It means the world to us,” Gale says. “We’re a part of the community.”

Islam says once they meet their goal of training 25% of restaurants this year, they’ll probably be eying 50% as the next benchmark. And they want to bring Narcan to other public gathering places where the health department has existing partnerships, like pools and hotels.

In the end, they’re hoping to get everyone Narcan trained. The overdose reversal medicine, and fentanyl test strips, are available for free to all Alexandria residents and businesses through the health department.

“Even if it saves one life, even if it saves 100 lives, it’s doing its job,” Islam says.

For anyone struggling with substance use, services — including opioid-specific treatments — are available through the Alexandria Community Services Board. Confidential help is also available through the national hotline of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Sarah Y. Kim

Sarah Y. Kim