Photo by andertho

Photo by andertho

Tucked away in a corner of Southeast D.C., bordered by the Anacostia River and the D.C. Jail, sits one of the city’s hidden gems, the Historic Congressional Cemetery. Founded in 1807, the burial list for the cemetery reads like a who’s who of local and national politics. Senators, Representatives, a vice president—you name it, and they’re likely interred there. Former FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover’s plot sits behind a wrought iron fence on one side of the grounds, while composer John Philip Sousa lays in a plot on the other side.

I stumbled upon the cemetery on a whim. I’d long ridden my bike past it, and decided to stop in one day with a friend. As I prepared to leave the grounds, something caught my eye. Tucked away at the intersection of two walking paths was a cluster of headstones that shared a unique quality—all of them openly awknowledged the sexual orientation of the grave’s resident. It’s not something you often see in cemetery, but then again, Congressional Cemetery is far from your average burial ground.

The most visually striking of all of the graves is that of Leonard Matlovich, a Vietnam veteran who rose to fame in 1975 by becoming the first gay service member to publicly reveal his sexuality, challenging the military’s long-standing ban on gays. After meeting with famed gay rights activist Frank Kameny in D.C., Matlovich hand-delivered a letter to his commanding officer declaring his sexual identity. Despite years of exemplary service and multiple tours of duty in Vietnam—which included a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart he earned after nearly being killed by a land mine—he was discharged.

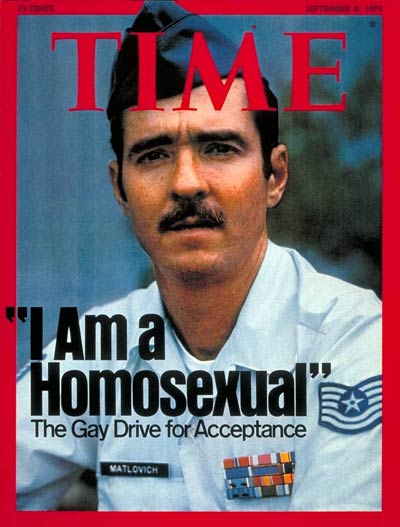

Leonard Matlovich, on the cover of Time Magazine in 1975

Leonard Matlovich, on the cover of Time Magazine in 1975His actions made him an instant celebrity and shed a bright light on the military’s outdated and bigoted policy. Matlovich and his case were everywhere—in every paper, on every television news show and even on the cover of Time.

He would spend the next five years in D.C. and San Francisco, fighting a protracted legal battle that would finally come to a head in September 1980. With the aid of the American Civil Liberties Union, Matlovich eventually won the right to reinstatement. Convinced, however, that the Air Force would find another reason to discharge him, Matlovich accepted a financial settlement and moved on. He chose instead to champion a number of gay-rights causes—he helped fight Proposition 6, which had sought to ban gay teachers in California schools, and was on the front lines of effort to promote awareness and adequate treatment of the rapidly spreading HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Tragically, that very illness would take Matlovich’s life in 1988. He fought until the very end, and delivered his last speech during a rain-soaked rally on the steps of the Capitol building in Sacramento. “Ours is more than an American dream,” Matlovich proclaimed. “It’s a universal dream. Because in South Africa, we’re black and white, and in Northern Ireland, we’re Protestant and Catholic, and in Israel we’re Jew and Muslim. And our mission is to reach out and teach people to love, and not to hate.”

Matlovich got the idea for his gravestone while living in Heidelberg, Germany. During his time in Europe, he and friends visited Historic Pere Lachaise Cemetery, paying their respects at the gravestone of life partners Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas and visiting the tomb of Oscar Wilde. Inscribed on the Irish poet’s tomb is a passage from “The Ballad of Reading Gaol,” which was written shortly after Wilde had been released from serving a two-year sentence for committing “homosexual offenses.”

And alien tears will fill for him,

Pity’s long-broken urn,

For his mourners will be outcast men,

And outcasts always mourn.

Matlovich resolved to create a place where gay and lesbian veterans could gather to remember their fallen brothers and sisters. Though D.C. was full of memorials to the fallen, there wasn’t one dedicated to those in the gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender community who’d been killed in the line of duty. During a walk through his neighborhood, Matlovich stumbled upon Congressional Cemetery and knew it was likely the perfect place for his headstone. Unlike Arlington National Cemetery, a massive sea of nondescript white grave markers that, while moving, also doesn’t allow much room for expression, Congressional would give him the ability to have his message heard long after his passing.

Matlovich’s grave as it sits today.

Matlovich’s grave as it sits today.

“When I was in the military they gave me a medal for killing two men and a discharge for loving one,” his headstone reads. Shaded by a tall, aging cherry tree, it’s made of the same type of mirror-like granite that the Vietnam Veterans Memorial is made of. Before his death, Matlovich instructed that his name not be placed on the headstone. Above his date of birth and death are two pink triangles, the symbol used in Nazi Germany to mark gays imprisoned in concentration camps.

It’s a moving tribute to a man who spent 12 years serving his country and another 10 fighting for an end to the ignorance and bigotry that plagued it, and a fitting memorial to all of his fellow veterans who paid the ultimate price—and often did so in shame, forced to conceal something as fundamental as their sexuality.

The site has become a mecca for gay and lesbian service members. Stephen Hill, the gay Army captain so memorably booed by the audience of a Republican presidential primary debate, was married in front of Matlovich’s grave. Gay veterans have gathered here over the years on Veteran’s Day, fulfilling his wish that his grave site be used as a memorial to all gay service members.

A group of gay veterans gathers in 2011 to honor their fallen comrades.

A group of gay veterans gathers in 2011 to honor their fallen comrades.

There are plans, however, for a much larger memorial at the cemetery. After over a decade of planning, the non-profit National LGBT Veterans Memorial purchased 10 plots just southeast of Matlovich’s grave.

“The purchased site measures approximately 15′ by 20′,” Historic Congressional Cemetery President Paul Williams told me via email. “Their purpose is to establish a burial area dedicated to gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender American veterans. They have recently issued a nationwide design competition for a central memorial to mark the area that will be composed of individual burial sites.”

Matlovich’s grave, however, is far from the only tombstone at Congressional that bears the name and sexual identity of it’s owner. Just across the path sits another headstone, this one belonging to Frank O’Reilly. “A Gay WWII Veteran,” reads the inscription on the uppermost portion of the tombstone. Below his name sits the epitaph—”During my eventful lifetime the only honest and truthful ending of the Pledge of Allegiance was ‘With Liberty and Justice for SOME.’ ” To the right of O’Reilly’s grave sits the future grave site of Tom “Gator” Swann, a prominent gay activist who has fought tirelessly to end the military’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy and to promote AIDS awareness.

The headstone of Frank O’Reilly

The headstone of Frank O’Reilly

Frank Kameny, the same gay rights advocate who helped Matlovich during his fight against the military’s discriminatory policy against gays, will soon be laid to rest in a plot just behind and to the left of Leonard’s. Kameny had been scheduled to be interred earlier in the year, but a disagreement between his estate and the group that purchased his grave site delayed the proceedings. His headstone, which had been previously installed on the site, is the same type of white marker used in Arlington National Cemetery. Beneath it will sit a stone which contains Kameny’s famous slogan: “Gay is good.” Though Williams told me that the exact details of the agreement were a private family matter, he assured me the interment was “indeed close to being resolved.”

The list goes on. Behind the Matlovich site sits another tombstone, similar in color and finish to the one in front of it, engraved with the name of Emanuel “Butch” Ziegler. The epitaph reads “A proud gay teacher and businessman.” On the corner of the intersection, a large granite bench contains the remains of Kay Batchelder. Congressional’s program director, Rebecca Roberts, told me that Batchelder’s estate executor “loved the idea of adding a lesbian to the gay neighborhood.” I counted several more headstones in the area engraved with the names of what appeared to be same-sex partners.

So why is this particular area of Congressional Cemetery such a popular choice when it comes to gay and lesbian burials? Roberts credits Maltovich’s memorial.

“People visit his lovely gravesite, see his provocative epitaph, and know of his courage as a gay rights advocate, and they want to honor his example,” she told me earlier this week. “Also, we as a cemetery are more than happy to accommodate same sex partners, have gay rights epitaphs engraved on the stones, etc. So people feel comfortable that they and their loved ones will be treated with respect here.”

Leonard Maltvich passed away 13 years before the end of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” and never lived to see the day when gay and lesbian service members could finally openly serve the nation they lived in. His fight, however, goes on even in death, as the LGBT community continues the fight for marriage equality and other basic rights that should be afforded to anybody, regardless of sexual orientation.

His battle cry still sounds as fresh today as it did 15 years ago: “I’m intensely proud to be gay and you should be, too. Unless we state our case, we’ll continue to be robbed of our role models, our heritage, our history, and our future.”