Yes, D.C.’s Chinatown is small in comparison to others around the world, but it still has a storied history. Here are ten things we bet you didn’t know.

1. The neighborhood’s boundaries are super contested

Officially, Chinatown stretches between 5th and 8th St NW and G Street and Massachusetts Ave NW. Within those bounds, buildings have to conform to the city’s “Chinese ‘Theme’,” which most famously includes having signs in Chinese (more on that later). But when UMD students interviewed 16 people who live or work in Chinatown and asked them what the boundaries of Chinatown are, they got…..16 different answers. In that spirit, please don’t @ us if we included or excluded something that you wish we hadn’t.

2. The Friendship Arch almost had a rival arch

The giant arch at 7th and H NW was believed to be the largest in the world when it was built in 1986. It is a massive architectural undertaking, boasting five roofs, 7,000 tiles, and 35,000 individual wooden pieces. There are almost 300 dragons painted or carved on its surface.

This style of arch is called a paifang and many Chinatowns have one. But weirdly, D.C. almost got two.

According to local historian John DeFerrari, the existing friendship arch was conceived after Chinatown was already on the decline. As a way to preserve some of the remaining Chinese culture, two neighborhood leaders proposed building the arch. Mayor Marion Barry got on board, and so did Beijing.

That caused a ruckus among members of Chinatown’s business community, many of whom hailed from Taiwan. According to DeFerrari Lawrence Locke, chairman of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association of D.C., told the Washington Post that the arch “might misidentify the local Chinese community with the Chinese communists.”

A year later, the CCBA and the city agreed to build two arches, the Friendship Arch at 7th and H, and a “Chinatown Community Arch” at 5th and H. The second group planned to put their community arch on 9th—or maybe even build TWO other arches. But ultimately they never put together a specific plan and the rival arch was never built.

3. The Chinese signs are mandatory

If you have a business within the official boundaries of Chinatown, you must have a bilingual sign. Sometimes those signs….get lost in translation. Academic Jackie Jia Lou writes in the scholarly volume Linguistic Landscape in the City that it’s often much less expensive to pick Chinese characters that translate to a generic description, rather than translating a brand. So for example, Legal Sea Foods’ sign translates to “Seafood restaurant.” The Capital One Arena’s sign says “Sports Center,” and Urban Outfitters is “Men and women’s clothing, household goods.” On the other hand, Subway’s Chinese name is a transliteration: “Saibaiwei,” which literally translates to “Most tasty among a hundred delicacies,” Jia Lou writes. (Subway has a presence in China, which probably explains why the company has a better translation of its name.) These generic descriptors, plus the fact that the Chinese signage is usually less visually prominent than the English sign—plus the fact that the neighborhood has a Subway and an Urban Outfitters–has led many to speculate that the signs are just putting a Bandaid on a Chinatown that is largely no longer Chinese.

4. There were never huge numbers of Chinese-Americans in Chinatown, but that’s not as important as the fact that it’s shrinking

Today, there are around 300 Chinese people living in Chinatown, most of them elderly residents of the Museum Square and Wah Luck House buildings. But the neighborhood was never as large as one might imagine.

Various estimates put the peak Chinese population somewhere between 1,000-3,000 residents. This was never San Francisco Chinatown, where 30,000 people live in 20 square blocks.

But more important to the remaining Chinese residents is a sense that the neighborhood’s identity is vanishing. The last Chinese grocery store closed in 2005, and now residents must take a bus to the suburbs–one that only arrives once a month. Sill, the remaining Chinese residents want to stay.

“My children have saved a room for me in their house [in the suburbs], but I rarely go there,” Wah Luck House resident Jia Ting “Tina” Xu told the Washington Post in 2011. “I don’t have a driver’s license, so what would I do?”

Although they recently survived the building’s sale, Wah Luck’s residents say they worry about its continued affordability, the Washington City Paper recently reported. Museum Square has also been the site of a major battle over affordable housing.

5. Before the area was Chinatown, it was something of a Germantown …

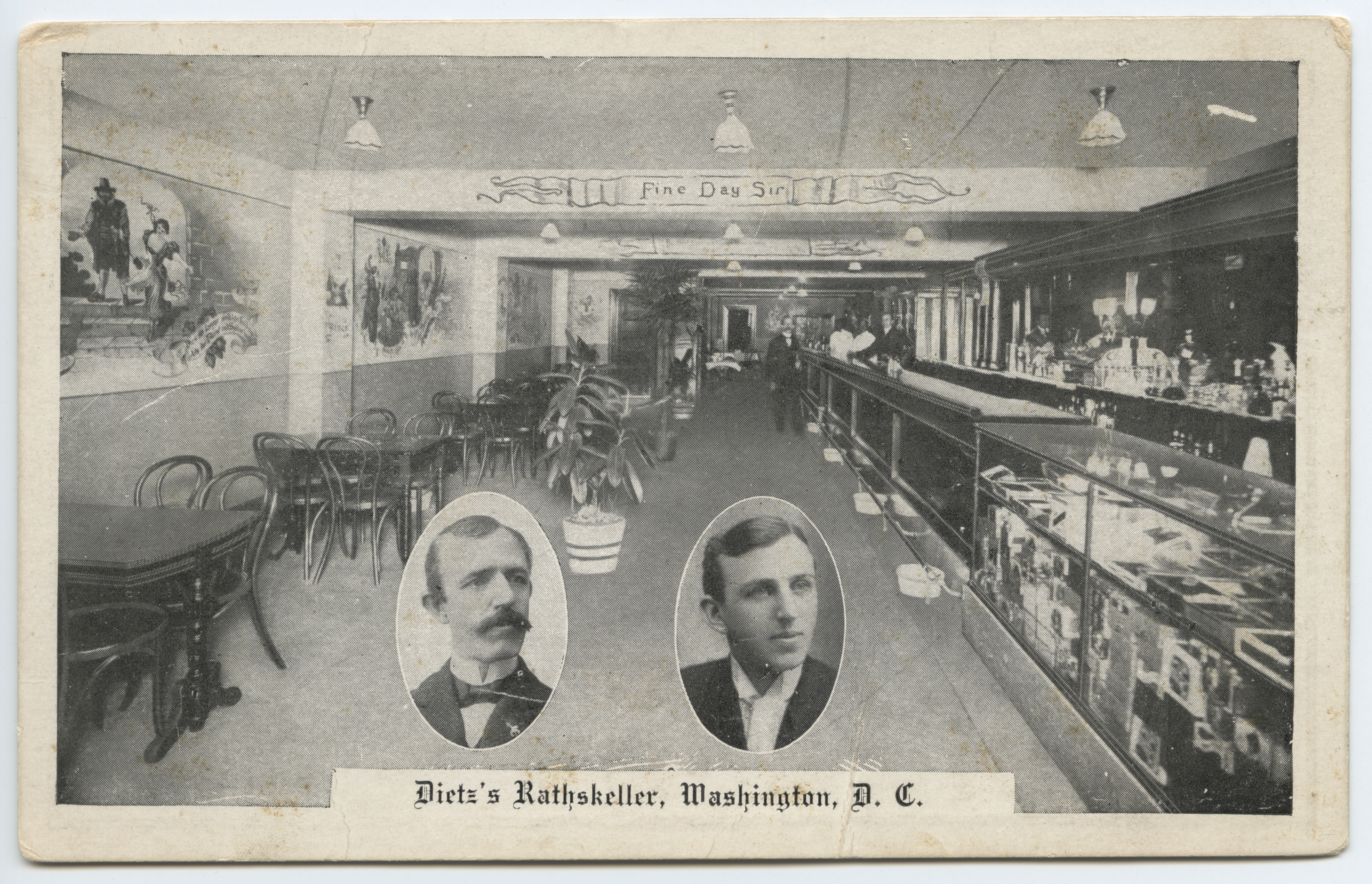

According to the Goethe-Institut, which used to be headquartered at 7th and I NW, 7th Street was once a hub of German-American life. Many buildings in the area belonged to German-American businesses (like Dietz’s Rathskeller, Herman C. Ewald’s confectionery, and Kloeppinger’s Bakery), or were designed by German-American architects, such as the Mercantile Savings Bank at 10th and G streets and Calvary Baptist Church at 8th and H streets. The German-American Heritage Foundation still runs a small museum on 6th St. NW in what used to be called Hockemeyer Hall. The late 19th century building belonged to merchant John Hockemeyer, a German immigrant who used it as a residence and a clubhouse. Chinese Americans moved in when the government tore down D.C.’s original Chinatown, at 4th and Pennsylvania.

6. … And a center of Jewish life in D.C. (still is!)

Sixth and I is now a Jewish cultural center that also holds services. But in 1907, it was just one synagogue among many in the area. According to one congregant quoted on Sixth and I’s website, “During the High Holidays all of us young people used to meet each other and walk up and down the streets between the synagogues. Maybe 500 to 1000 people would be walking the streets. It was like Broadway.”

Sixth and I was built by the Adas Israel congregation when they outgrew their original building. That group stayed there until 1951, when the congregation moved out to a bigger space in Northwest. The Moorish/Romanesque/Byzantine (yes, it’s sort of all three) building became an African Methodist Church until the early 2000s, when that church moved to the suburbs and put the building up for sale. Within 24 hours, three developers from the Jewish community had purchased the building to turn it into its current form.

Side note: Adas Israel, the congregation that originally built the synagogue? The Chinatown building they had moved out of is now the Lillian and Albert Small Jewish Museum, perhaps most famous for having been moved three times.

7. The area used to be lousy with art galleries

“Gallery Place” isn’t just referring to the National Portrait Gallery. In the 1970s and 1980s, the neighborhood was full of visual art galleries, performance spaces and clubs. Research by curator Blair Murphy (disclosure: Blair is a friend) found that two dozen venues existed just within one block, on 7th Street between D and E streets, and plenty more lined the streets further out. When Flashpoint on G Street closed in 2017, it was one of the last small art spaces downtown. Here’s a DCist story about the glory days of d.c. space, one of the most famous (or infamous).

8. The Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum is legit

The unassuming building at 437 7th Street NW looks a little fake-y from the outside, but it’s legit. Clara Barton, the founder of the American Red Cross, ran the Office of Missing Soldiers out of this space. She lived here for eight years and helped locate and identify 22,000 soldiers missing or killed in action in the Civil War. Later, she simply closed the office and left. The owner of the building boarded up the third floor, and soon after, D.C. adjusted its address system and the building was “lost.”

In 1997, the GSA, which owned the building, sent an inspector to the site so the agency could make sure the building could be torn down. On the third floor, the museum says, Richard Lyons “felt something (or someone) tap his shoulder.” Exaggerations aside, he found an envelope hanging out of the ceiling. He grabbed a ladder and climbed to the attic and found Barton’s office and living quarters untouched–a perfect time capsule more than 100 years old. After $6 million in renovations to restore the site, the Missing Soldiers Office Museum opened in 2015.

9. The house where John Wilkes Booth plotted to kill Lincoln is still standing

The Mary Surratt house is now Wok N Roll, and its outside (and presumably its inside) has changed a bit, but it’s the same house—with a plaque to prove it. Mary Surratt ran a boarding house there where John Wilkes Booth and co-conspirators Lewis Powell and George Atzerodt all stayed. Surratt’s role is still disputed by historians.

Long digression: You’ve heard the story of John Wilkes Booth’s assassination of Lincoln a thousand times. You might not know that the plot was much deeper than that. Atzerodt was tasked with killing Vice President Andrew Johnson (he chickened out), and Powell spectacularly failed at killing Secretary of State William Seward, in such a way that might in fact have brought down Surratt, too.

Here’s the story. Secretary of State Seward is in his bed, literally in traction after having been thrown from his carriage a week or so prior. Powell manages to get into the Seward home and to the third floor, where he attempts to shoot Seward’s son, but his gun misfires. He then gets into the bedroom and stabs Seward multiple times—who, remember, has multiple broken bones and is literally lying in bed defenseless—and somehow fails to kill him. Thinking Seward is dead, Powell runs out into Lafayette Square…and promptly gets lost.

Powell wanders D.C. for THREE DAYS. It is unclear what he did during that time, but he managed to get to Fort Bunker Hill (now part of Brookland) where he threw away his coat, which contained a girlfriend’s hotel room number and a fake mustache. Historians aren’t sure if he just walked around randomly (he’d long lost his horse) or what. One historian claims he sat in a tree for three days. Finally, he makes it back to Mary Surratt’s house, just as police are making a routine follow-up visit. He’s disheveled, wearing his undershirt sleeve as a hat (thinking this is a good disguise) and carrying a pickaxe. Surratt claims not to know him, and Powell claims he’s a ditch-digger. The police are understandably suspicious, and he’s taken into custody, later arrested and eventually executed. Some historians believe that without Powell’s untimely arrival, Surratt would not have been convicted. She was the first woman executed by the federal government.

10. The building that contains the National Portrait Gallery and the Smithsonian American Art Museum has a wild past.

There’s too much to go into here, but before it housed museums, it was the Patent Office, a Civil War military hospital, and a number of other government offices. The Bureau of Indian Affairs was once located here, and Walt Whitman worked there. He had been working on updating Leaves of Grass, and the then-secretary of the Interior found a copy in his desk. (Whitman said the book was in a private drawer and the secretary was snooping.) So offended, Secretary Harlan fired Whitman immediately. You can read the whole story in historian Garrett Peck’s Walt Whitman in Washington, D.C.

Want more?

Ten Facts You May Not Know About Spring Valley

Ten Facts You May Not Know About Navy Yard

10 Facts You May Not Know About Brookland

Ten Facts You May Not Know About Anacostia

Ten Facts You May Not Know About Dupont Circle

Nine Facts You May Not Know About The Southwest Waterfront