You’d expect a cemetery to brim with history, and Congressional Cemetery doesn’t disappoint. You’ll find the graves of such notable figures as Civil War photographer Mathew Brady and J. Edgar Hoover, the FBI’s first director, there. But you might not imagine the 35-acre cemetery is as lively as it is: It hosts several 5Ks, concerts, and outdoor movie nights, as well as a book club and yoga classes, and plenty of dogs and their owners frequent the grounds, too. Here are 10 facts you might not know about the Congressional Cemetery.

1. The cemetery is not government property.

Despite its very official-sounding name, Congressional Cemetery comes from humble roots. For the first few years, the then 4.5-acre cemetery had no special name, having been established in 1807 by eight Washingtonians as a private burial ground. As NPR explains, when Sen. Uriah Tracy of Connecticut died in 1807, there wasn’t any railroad tracks between the District and his home state and embalming was uncommon, so he needed a local burial. The cemetery was chosen, and Tracy became the first member of Congress to be interred there.

In 1812, the land owners handed the property over to Christ Church, an Episcopal church on G Street SE and the cemetery was branded “Washington Parish Burial Ground.” The church began setting aside plots for members of Congress. By the 1820s, it had become the traditional burial site for lawmakers and other high-ranking federal officials who died in Washington, according to the National Cemetery Administration. It began to be referred to as “Congressional burying ground” and the “American Westminister Abbey.” Recognizing the cemetery’s growing significance, Congress even appropriated funding in the 1830s for its upkeep and landscaping. Its nickname was later shortened to “Congressional Cemetery.”

Its management has been handled by the nonprofit Association for the Preservation of Historic Congressional Cemetery since 1976, as the church could no longer afford to maintain the grounds. But Christ Church continues to maintain a close relationship to the property: Parishioners volunteer as docents for guided tours, and its rector is an ex-officio member of the cemetery’s board.

2. You don’t have to be a congressman to be buried there — you just have to be dead.

There are approximately 90 senators and members of the House interred at the cemetery. After Arlington National Cemetery was established in the bloody wake of the Civil War, Congressional Cemetery no longer became the choice spot for public officials. Tens of thousands of other people have been buried there over the years. Plots range from $4,000 on the cemetery’s east end to $8,000 in the more historic sections.

Congressional Cemetery is also believed to be unique in having a section dedicated to the LGBTQ community. Leonard Matlovich, who was discharged from the Air Force for being gay in the 1970s, purchased a plot near J. Edgar Hoover and his rumored romantic partner Clyde Tolson. Matlovich’s carefully designed headstone inspired others, especially veterans, to join him in the afterlife, as Atlas Obscura recounts.

To make it easier to find such landmarks, the cemetery has a mobile app to search records and tour the grounds, along with a series of walking tour guides that you can download and take with.

And you don’t have to be a human to be buried there, either: The cemetery opened a portion of its grounds as the District’s first pet cemetery earlier this year. Special places in the Kingdom of Animals section would be reserved for members of the K9 Corps, the cemetery’s dogwalking program, DCist reported in May, but other plots are available to any pets — not just man’s best friend.

3. Grave robbers stole the skull of a former U.S. attorney general from a vault on site.

The strange tale revolves around William Wirt, a lawyer who rose to prominence in America’s fledgling years as the U.S. attorney general under Presidents James Monroe and John Quincy Adams. Wirt even ran unsuccessfully as a third-party candidate for president in 1832. (He still holds the record for the country’s longest-serving attorney general, having held the post from 1817 until 1829, and he “is widely credited with turning the job into a position of national influence,” according to a post on In Custodia Legis, a Library of Congress blog.) But, having died in 1834 deeply in debt, the 61-year-old was buried in a plain grave in Congressional Cemetery. Wirt’s remains were later reinterred in an impressive family vault constructed by his son-in-law in the 1850s.

There was no reason to be concerned about the whereabouts of Wirt’s skull until 2003, when an anonymous caller asked then-cemetery manager Bill Fecke if he would like it back. The caller never produced the skull, but it led to a cursory investigation that indicated the vault’s lock had broken some time ago — a large slab of granite had then been set there to bar the entrance. Things took an even stranger twist when District councilmember Jim Graham called the cemetery in early 2004 to say he had come into possession of the skull in question. (The Washington Post reported in 2005 that Graham said he acquired the skull from Allan Stypeck, owner of Second Story Books, who said got it after he was hired to appraise an eclectic collection that had belonged to the deceased Robert L. White. Stypeck found the skull, and other Wirt memorabilia, among the items.) Graham wanted to return the skull, which was in a conveniently labeled box that said “Hon. Wm. Wirt”, to its rightful home, but cemetery staff had yet to access the vault to confirm any body parts were missing. When they finally entered the vault in 2005, they found the eight coffins and their remains in disarray. Smithsonian anthropologists were called in to identify the skull’s rightful owner, and after some sleuthing, it was determined to that it actually was Wirt’s. Who stole it, though, remains a mystery.

4. President Harrison spent more time in the cemetery’s Public Vault than he did in office.

On April 4, 1841, President William Henry Harrison became the first chief executive to die in office. He died a mere 32 days into his term, having contracted an illness. (It has been a commonly held belief that Harrison’s two-hour inaugural address caused him to catch a cold that later morphed into pneumonia, but some scholars believe he may have been sickened by contaminated water.) Regardless of the true cause of his death, Washington strove to mourn its loss properly. Black drapes were prominent at the White House and the U.S. Marine Band played dirges on the procession out to Congressional Cemetery, where his remains were laid in the Public Vault “until the lingering winter in Ohio had passed, and it was a more appropriate time to send Harrison’s remains home,” the White House Historical Association explains. Harrison spent about three months in the vault. His body was then brought to its final resting place, Mt. Nebo in North Bend, Ohio, where he was buried in a family tomb on July 7, 1841.

The cemetery’s Public Vault has also held the remains of other famous Americans, most of them for a brief period of time before their burial, but first lady Dolley Madison’s body laid there for about two years after her death. The vault fell out of regular use in the 1930s, according to Congressional Cemetery. By 2003, the sandstone vault had degraded so far that Congress appropriated $100,000 for cemetery improvements, including the vault’s renovation.

5. The FBI indicted cemetery superintendent John Hanley for fraud, waste, and abuse in 2000.

Congressional Cemetery put out a fairly cringe-worthy notice to its association members in a spring 2000 newsletter detailing the story of John Hanley, who served as the cemetery’s superintendent from 1989 until 1997. Hanley, the newsletter says, managed the cemetery “virtually alone and made a great deal of progress in maintaining and improving the grounds.” But he apparently conducted a great deal of financial mismanagement, as well: By 1996, the association was on the brink of insolvency, and the IRS had even put a $17,000 lien on the cemetery for unpaid taxes, The Washington Post later reported. Law enforcement got involved, and Hanley resigned at the association’s request in February 1997. He was indicted in 2000 on charges of embezzling more than $175,000 from cemetery clients and donors (among those funds was nearly $5,000 intended for the upkeep for J. Edgar Hoover’s grave site, according to the Post). It was a dark time for the cemetery, which couldn’t afford paid staff by that point and relied on volunteers, who worked hard to drum up desperately needed funding. Congress extended a $1 million matching grant to the cemetery in 1999, matching donations dollar for dollar, and the cemetery slowly rebuilt its coffers.

6. There are roughly 25,000 headstones, but more than 67,000 people buried there.

What accounts for the discrepancy? Some may have had their grave markers stolen, others are interred in family vaults, and many are buried in unmarked, forgotten graves. According to Christ Church’s history, more than half of the dead buried there are children, which is attributed to the “appallingly high infant mortality rate in the 19th century.” In 2013, the cemetery hired Bob Perry to help map it and locate graves using radar.

Still, other graves at Congressional Cemetery lack headstones by a deliberate choice: David Herold, who was hanged for his role in President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, was reinterred on the cemetery grounds in 1869. The cemetery director chose keep his plot unmarked, though, in a bid to keep vandals away, NPR reports.

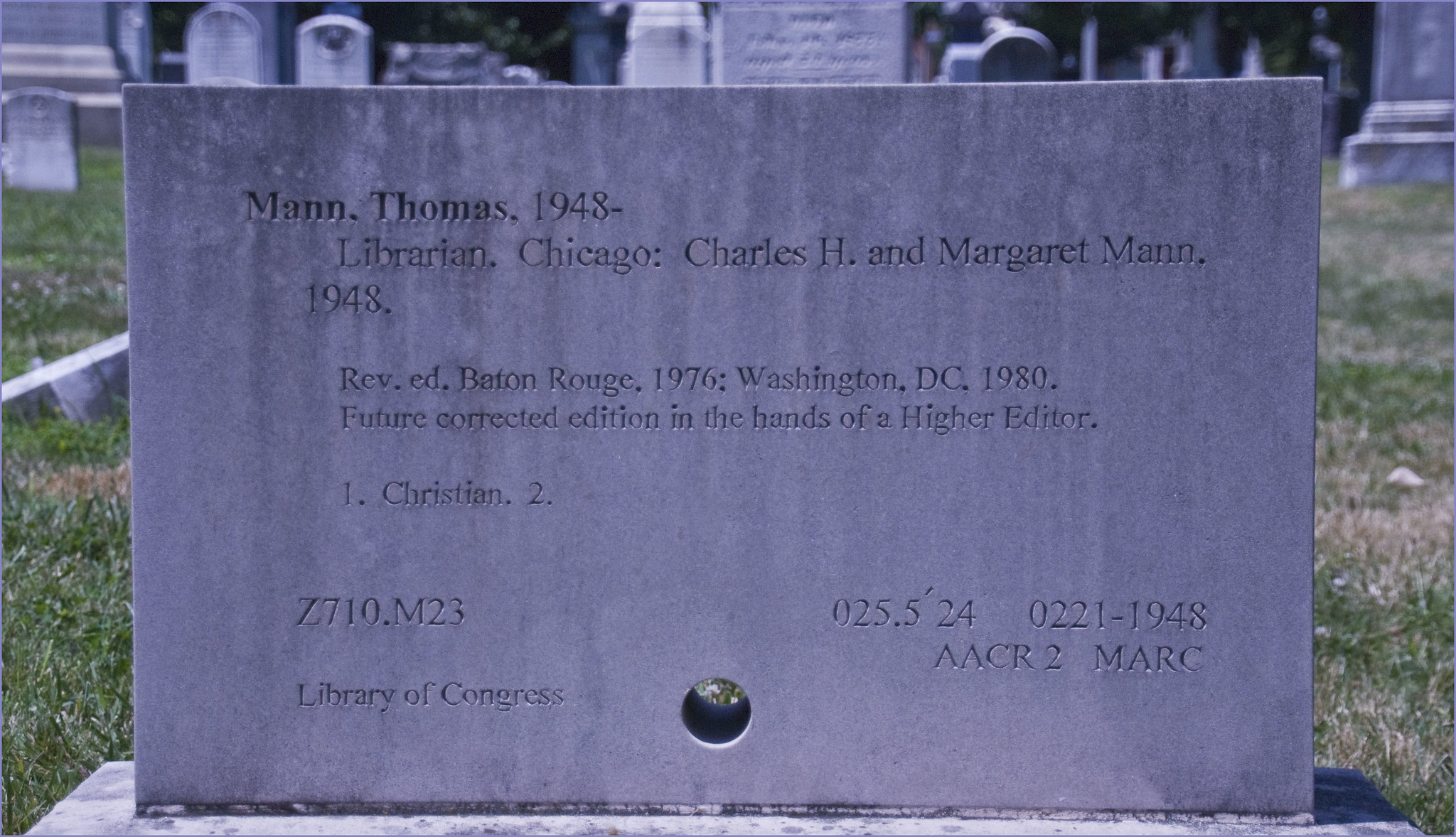

Tucked among the headstones, though, thorough cemeterygoers will find creative nods to various lives. Take the future grave of Thomas Mann, a former librarian at the Library of Congress who is still alive, for example: His headstone is modeled after an entry in a library card catalog, complete with a hole punched through the bottom. “Future corrected edition in the hands of a Higher Editor,” it reads. Meanwhile, the grave belonging to Sally Wood Nixon is modeled after a china cabinet, with her ashes in an urn behind its glass doors, as she was an avid china collector, according to a Washington Post story.

7. The cemetery celebrates one of its most famous residents, John Philip Sousa, annually.

Legendary conductor and composer John Philip Sousa was born in 1860 at 636 G Street SE, about a mile west of the cemetery. The native Washingtonian spent seven years as a musician in the U.S. Marine Corps band, and he later returned to it as its conductor, a position he held for 12 years. According to his Marine Corps biography, Sousa “shaped his musicians into the country’s premier military band.” He garnered so much acclaim for his rousing marches — including the “Washington Post” march, “Semper Fidelis” (the Marine Corps’ official march), and “The Stars and Stripes Forever” (the country’s national march) — that he earned the fitting title of “March King.” Upon his death in 1932, he laid in state at the Band Hall at the Marine Barracks. His funeral procession, which included his beloved Marine Corps band, playing marches Sousa himself wrote, wound its way to Congressional Cemetery, according to news reports at the time. The cemetery hosts an annual celebration and wreath-laying in Sousa’s honor on Nov. 6, his birthday, and the Marine Corps band holds a graveside concert.

8. The cemetery derives close to 25 percent of its operating income from its dogwalking program.

The K9 Corps, established more than two decades ago, is a well-known and well-loved part of the cemetery, with good reason. Dogwalkers serve as an unofficial security detail, a source of helping hands (members are asked to contribute eight volunteer hours annually), and a significant income stream, bringing in about $250,000 annually. The base membership fee is $235 a year, and account holders may register up to three dogs, for a fee of $50 per dog (at least one must be registered).

The program, which is capped at 770 dogs, is so popular there’s a waitlist. You even have to pay $80 for a waitlist spot— and the K9 Corps website warns that potential members “should expect to be on the waitlist for over a year,” as the annual membership renewal period occurs in January, and open slots become available to waitlist beginning in February. Day passes for dogwalking are also available for $10.

But many dog owners say they are happy to pony up the money. Hill East resident Victor Romero, who frequents the cemetery with his wife and dog, told WAMU in 2018 that “we think of it as a community center for the most part.” The grounds are also fully enclosed by a fence, so owners can let their pups off-leash without fear of unwanted escapees. And the cemetery’s four-legged friends and their owners make an important contribution to, as a story on the National Trust for Historic Preservation put it, the “esprit de corpse” that sets the cemetery apart from others.

9. The 171 unusual, blocky markers commemorate members of Congress who died in office.

The mastermind behind the squat sandstone blocks with pointy tops was Benjamin Latrobe, one of the architects of the U.S. Capitol. They’re known as “cenotaphs,” which means “empty tombs.” Their Egyptian design, unusual for its time, stemmed from Latrobe’s desire to honor the memory of the lawmakers who died serving their country. He also wanted his monuments to stand the test of time. The cenotaphs were constructed out of Aquia Creek sandstone, which is the same stone originally used in the Capitol’s exterior. About 60 have bodies interred under them, but many do not. The cemetery stopped adding cenotaphs in 1877 as the tradition began to seem “old-fashioned,” according to an audio tour of the cemetery. They were also not particularly popular with the public or with members of Congress. Sen. George Hoar of Massachusetts is said to have remarked that being buried underneath one would “add a new terror to death.”

10. You can get married in the cemetery’s chapel.

You don’t have to be dead to take part in a ceremony at the chapel: Congressional Cemetery rents out both its charming little chapel, which was constructed in 1903, and its conference room as event space. The chapel can seat as many as 100 guests, excluding any ghouls who may be watching from the shadows. And yes, people do get married there, though whether you choose to have it be a cemetery-themed wedding is, of course, up to you.

This story has been updated to reflect that President John Quincy Adams was interred at the Public Vault, but was not buried at Congressional Cemetery

Previously:

10 Facts You Probably Didn’t Know About Union Station

10 Facts You May Not Know About National Airport

10 Facts You May Not Know About Friendship Heights

10 Facts You May Not Know About Takoma

10 Facts You May Not Know About Columbia Heights

10 Facts You May Not Know About Petworth

10 Facts You May Not Know About Chinatown

10 Facts You May Not Know About Spring Valley

10 Facts You May Not Know About Navy Yard

10 Facts You May Not Know About Brookland

10 Facts You May Not Know About Anacostia

10 Facts You May Not Know About Dupont Circle

Nine Facts You May Not Know About The Southwest Waterfront

There’s No Paywall Here

DCist is supported by a community of members … readers just like you. So if you love the local news and stories you find here, don’t let it disappear!