It’s a cold Sunday morning in April at the National Zoo, and a small group of dedicated “panda people” are watching young Xiao Qi Ji climb over his mother Mei Xiang.

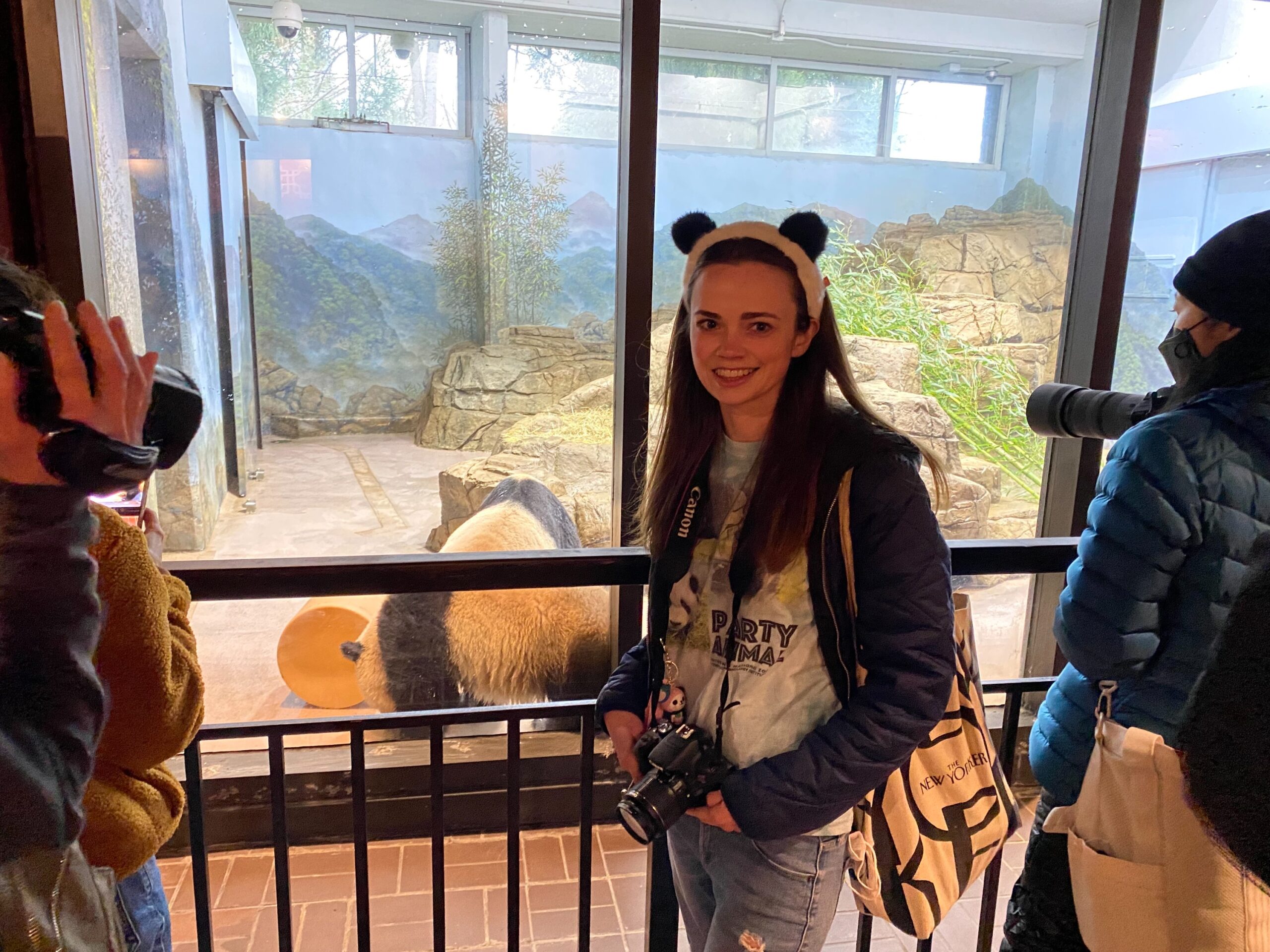

“I don’t know if she likes it, but she’s definitely tolerating it,” D.C. resident Kirsten Svane says, camera in hand and a pair of panda ears on her head.

It’s only a week before the big “pandaversary,” marking 50 years since giant pandas arrived at the National Zoo. Watching the energetic furball put on a show for the handful of humans here on this chilly morning, Svane wonders aloud how the baby panda will act when the throngs surely show up next weekend.

“I’m curious… because on his birthday weekend, he knew it was his birthday. He knew,” she says. “He was a little kid, hopped up on sugar, like, ‘this is all about me.’”

Svane moved to D.C. from New Jersey right before the pandemic. She lives “ten steps” from the National Zoo, so ever since the zoo reopened for visitors last spring, she says she’s come once or twice a week to visit the three pandas – Mei Xiang, adult male Tian Tian, and their cub, almost 20-month-old Xiao Qi Ji.

“It’s peaceful, pure joy, and panda happiness,” Svane says. “I don’t know where I would be right now without these guys, to be honest. These guys kinda saved me [during the pandemic]. I’m very grateful.”

Also here this morning is Cyndy Taylor of Fairfax, clad in a cartoon panda t-shirt. Taylor grew up visiting the pandas with her brother and dad every spring break, hearing over and over again about how these black and white bears ended up in the nation’s capital. The last day she spent outside the hospital with her brother before he died unexpectedly in 2017 was here, with the pandas. Her weekly trips to see the three bears now remind her of family members who are no longer with her.

“There’s just something about them that makes you smile and makes you feel happy,” she says.

Tsaiwen Hu, holding an old school handheld camcorder, stands nearby. She puts together panda videos for a panda-centric Youtube channel. Over the last two years, she’s made regular visits from her Southwest D.C. home as well as being a frequent watcher of the panda cam.

“I kind of look at [Xiao Qi Ji] like he’s my baby. I have to check on him and make sure he’s okay,” Hu chuckles. “Sometimes I say it’s an addiction. But I… feel happy watching them.”

For the uninitiated, it might seem odd to simply happen upon this many passionate panda enthusiasts on a random Sunday in April. But in D.C., this all sounds about right.

For five decades, the pandas have provoked something like a widespread local frenzy, adored and cherished by residents who treat the bears as they might a revered celebrity. We know all their names; we wait with bated breath for news of a panda pregnancy; we celebrate birthdays and mourn difficult goodbyes. People wear panda suits, buy panda merchandise, and attend panda-themed events. The pandas are D.C., and D.C. loves its pandas.

So … how did all this happen? On their fiftieth anniversary in the city, here’s a look back at panda history in the District: how they got here, how they’ve fared, and how we’ve grown to love them.

Like many love stories, this one started off a little chilly – or, perhaps more accurately, it started in a bid to make things a little less chilly.

In February 1972, President Richard Nixon and First Lady Pat Nixon made a historic visit to China in an attempt to foster a warmer relationship between the two countries. As the story goes, the First Lady spotted some very cute black and white bears during a trip to the Peking Zoo. Charmed, she remarked to Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai at a banquet later how much she liked the animals. Reportedly, he responded simply, “I’ll give you some.”

Two months later, a pair of young pandas — a female named Ling-Ling and a male named Hsing-Hsing — were on their way to D.C. In exchange, the U.S. sent two Arctic musk oxen named Milton and Matilda.

While the two were not the first pandas to grace American soil, the animals still had an air of mystery around them. For years, the Chinese government had isolated its country from the rest of the world. By giving America two of its native bears, the animals became political tools – so-called “panda diplomacy.”

“It was a gesture of goodwill,” says Jim Byron, President of the Richard Nixon Presidential Library in California. “Both the United States and China had something to gain from a relationship with each other at that time. So, both sides were looking for ways to make an impression.”

Fifty years on, panda diplomacy has its share of detractors, including those who argue the lovable bears serve to help China evade scrutiny for the government’s history of human rights abuses.

But the pandas themselves have been widely beloved from the start. The New York Times described “polite warfare” among zoos at the time vying to host the animals. But, of course, we know who won that battle.

On April 16, 1972, First Lady Pat Nixon welcomed the pandas to the National Zoo.

The young panda couple quickly became the zoo’s stars, eliciting long lines of admirers excited to see the bears mostly eat and sleep. An estimated 75 million people came to see the pandas over their lifetime at the National Zoo.

Early keepers had to spend time learning to care for pandas in captivity – the National Zoo had never had pandas before, and there hadn’t been any on American soil in more than two decades. Perhaps the most confounding of these struggles was the grueling and protracted effort to get Hsing-Hsing and Ling-Ling to have sex – conservation and population supplementation is, after all, ostensibly the point of keeping these rare animals in captivity.

Unfortunately, the pair didn’t seem terribly interested in the idea. For years, keepers’ efforts at fostering romance were fruitless. Hsing-Hsing was “never able to establish an effective posture,” then-director of the zoo Theodore Reed once told the Washington Post, and “may also have been victimized by a poor self-image,” per the outlet.

Ling-Ling was no better, and no more interested, in the endeavor.

“When it’s time for those animals to breed, they need to like each other. If they don’t like each other or if there is no feeling, well, nothing is going to happen,” Dr. Pierre Comizzoli, a research biologist at the National Zoo and a panda reproductive expert, tells DCist/WAMU. “That’s a problem we’ve encountered not only with the giant panda but with a lot of other species.”

Eventually, however, love prevailed, and fanfare was momentous in the District. Here’s a part of a restrained write-up from the Washington Post in 1983, the year the panda pair finally consummated their union:

The couple went on to have five cubs together, but they were never able to parent their babies – all died within days of being born.

Ling-Ling herself died suddenly in 1992, another tragic day for the National Zoo.

But Hsing-Hsing lived to the ripe old age of 28 (pandas in the wild typically only live 15 to 20 years). Laurie Thompson, the National Zoo’s assistant curator of giant pandas, joined the zoo in 1994 and got to know Hsing-Hsing in his elder years.

“He was very laid back… a very sweet panda,” Thompson remembers. “He liked to play with us through the mesh area. He would put his feet under the mesh and… we would tap at his feet.”

Thompson says taking care of Hsing-Hsing taught her myriad things about caring for the animals: managing their arthritis, training them for medical care, and keeping them mentally stimulated.

“Hsing-Hsing had his diet of bamboo and then some fruit. But we just sort of put it out and didn’t make him work to get it,” she says. “Now, we do things like cut up fruit and put it in feeders and they have to kind of roll them around and shake it to get the food out. And that helps keep them busy and more mentally stimulated.”

Almost exactly a year after Hsing-Hsing’s 1999 death, the zoo cut a new deal with the Chinese government for two more pandas, this time on loan. Thus began the era of Mei Xiang and Tian Tian, the panda parents who have been at the zoo for more than two decades now.

The pair has had their own share of mating and breeding troubles. Despite years of maneuvering from conservationists at the zoo, the pair has simply never figured out how to have sex. The New Yorker outlined the troubles in a detailed piece from 2013:

Still, through the scientific miracle of artificial insemination, Mei Xiang and Tian Tian have had four surviving cubs: Tai Shan, Bao Bao, Bei Bei, and Xiao Qi Ji. They form part of a largely successful story about panda conservation over the last 40 years. In the 1980s, there were perhaps fewer than 1,200 pandas in the Chinese forests. Today, that number has nearly doubled (though, Comizzoli cautions that no one really knows the exact number since it’s very hard to see pandas in dense bamboo forests). There are another approximate 600 pandas under human care, up from about a hundred three decades ago.

In fact, giant pandas are no longer considered endangered in China.

Much of this can be attributed to the two pandas becoming, quite literally, the symbol of wildlife conservation.

“We know that by saving and helping this species, we are also helping a lot of other species that are sharing the same habitat,” says Comizzoli. “It’s [become]… a model for conservation.”

The zoo’s pandas are all remarkably different from one another, with clear and distinct personalities, says Dr. Brandie Smith, a former curator of the giant pandas and head of animal care. She calls Mei Xiang “thoughtful” and “intellectual,” while Tian Tian is more “matter of fact.” A perfect example is how they approach the toys that the keepers hide their food in.

“[Mei Xiang] will look at the toy, she’ll twist it, and she’ll turn it very delicately… and Tian Tian is a little bit more straightforward,” laughs Smith, who’s now the director of the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. “He’ll just smack it against something until the enrichment falls out.”

Bao Bao, who was born in 2013, was more like her mother (“calm” and maybe even a “little standoffish”) while Bei Bei was “a rough and tumble boy” and “quite the performer.”

Xiao Qi Ji, likely 22-year-old Mei Xiang’s final cub, was a special birth for the zoo, taking place as it did in the middle of the intense first year of the pandemic. With a COVID vaccine still months away for both humans and animals, staff made the choice not to collect fresh semen from Tian Tian but, rather, use a several-year-old frozen sample to artificially inseminate Mei Xiang.

Comizzoli says using only frozen semen had rarely ever been done and a risky choice. But it was done one out of necessity to limit the number of humans (and pandas) in the same place at the same time.

The gambit worked, marking the first documented pregnancy from frozen semen in the United States.

Five months later, Xiao Qi Ji — a Mandarin phrase meaning “little miracle” — was born, and Mei Xiang became the second oldest panda in the world to give birth.

At a time when the pandemic was raging, an adorable (or … maybe not?) baby panda set off such a wave of euphoria in D.C. that the panda cam crashed. Over the last 20 months, we’ve seen Xiao Qi Ji eat a sweet potato, frolic in the snow, and devour a birthday cake.

The local obsession with pandas does not seem to be waning, and it extends to the folks who work with the animals, too. No matter how long she’s been working with the pandas, Smith says it never gets old. Their big eyes and round heads, how they crawl around like babies — it’s all nearly too much.

“Pandas are almost perfectly biologically designed to be cute for humans,” she says.

Comizzoli agrees.

“There is something magic about these animals,” he says.

After 50 years, the pandas have also become a part of the fabric and history of D.C.

“It’s kind of a generational thing…you hear all of the time people saying, ‘Oh, I came here when Ling-Ling and Hsing-Hsing were here.’ It’s like a sort of history of D.C.,” says Laurie Thompson. “They are obviously very cute too.”

But the good times may not last. Since 2000, as part of an agreement with the Chinese government, when a panda born in the U.S. turns four years old, they must be sent back to their homeland. This has resulted in some pretty tearful goodbyes.

Then, late last year, as part of a new agreement with the Chinese government, it was announced that all three pandas – including baby Xiao Qi Ji — will go back to China at the end of next year.

While this may inspire some heartache across the District, Smith says not to worry. They’re already in talks about a new agreement that will keep pandas at the National Zoo “forever.”

There’s still a lot to learn about giant pandas, say Smith and Comizzoli: about reproduction, their sensitivity to pathogens, and how they teach one another.

“There’s a lot to get upset about in the world right now. Giant pandas are not one of them,” Smith says. “We are absolutely committed to having giant pandas at the National Zoo.Our relationships with our colleagues in China are great and we’re very hopeful that the program will continue and that people can have some new pandas to welcome here in the future.”

Back at the National Zoo on a Sunday morning, more people have arrived to witness the pandas. The crowds have moved inside of the habitat to watch mother and son lick honey off enrichment objects. There’s a joyous murmur from the people watching the pandas tuck into their treats.

In the two years since she’s been coming to see the pandas on a regular basis, Kirsten Svane has seen Xiao Qi Ji grow up.

“I feel like I’ve developed a relationship with them, seeing them every day,” she says, a smile on her face. Just like much of the rest of the city, Svane can’t get enough of these black and white bears.

“I love talking to anybody about the pandas.”

This article was updated to correct Brandie Smith’s title.

Matt Blitz

Matt Blitz