Before the curtain of the second performance of Washington National Opera’s new production of Mozart’s Don Giovanni on Monday night, conductor Plácido Domingo made an announcement. Happily, it was not to announce a cast change, but to draw the audience’s attention to the fact that it was the 220th anniversary of the opera’s first performance in Prague (October 29, 1787). This production is not likely to rank high on anyone’s list of noteworthy versions of Don Giovanni, in spite of the auspicious occasion, but the singing was generally good, sometimes excellent.

Director John Pascoe has rethought his 2003 production with different costumes and sets. Pascoe has said that his new concept revolves around the idea that Don Giovanni “has to be an incredibly seductive figure . . . looking like a magnificent sexually driven animal in the first act.” While the fanciful costume designs gave the impression of Don Giovanni transported to the world of The Crow or X-Men, on the stage it is much tamer. Pascoe draws an axis of opposition between two central characters, Don Giovanni and Donna Elvira, costuming them similarly in a cross between light bondage fetish (tight leather pants for him, leather bustier for her) and 19th-century fashion (Napoleonic military uniforms, Victorian dresses). The sets evoke a warm climate of palm trees, with Spanish dancers in the peasant scene at the end of Act I and neoclassical architecture made of riveted steel girders (the Don’s “prison,” according to Pascoe’s Director’s Note). The staging, with its references to Franco’s Spain, adds little to the story, and far more importantly it mostly does not detract from it.

Director John Pascoe has rethought his 2003 production with different costumes and sets. Pascoe has said that his new concept revolves around the idea that Don Giovanni “has to be an incredibly seductive figure . . . looking like a magnificent sexually driven animal in the first act.” While the fanciful costume designs gave the impression of Don Giovanni transported to the world of The Crow or X-Men, on the stage it is much tamer. Pascoe draws an axis of opposition between two central characters, Don Giovanni and Donna Elvira, costuming them similarly in a cross between light bondage fetish (tight leather pants for him, leather bustier for her) and 19th-century fashion (Napoleonic military uniforms, Victorian dresses). The sets evoke a warm climate of palm trees, with Spanish dancers in the peasant scene at the end of Act I and neoclassical architecture made of riveted steel girders (the Don’s “prison,” according to Pascoe’s Director’s Note). The staging, with its references to Franco’s Spain, adds little to the story, and far more importantly it mostly does not detract from it.

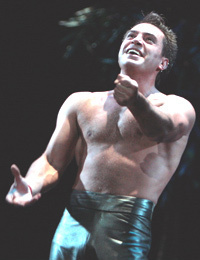

The casting is much more in line with expectations for the company than the season opener, La Bohème. Uruguayan baritone Erwin Schrott reprises his 2003 Washington appearance in the title role, with vocal and dramatic appeal beyond his smarmy, bare-shirted physical presence. He owns the role in many ways, even eying up women in the audience to put across his status as universal seducer. The only false note of the evening — presumably the choice of the director — was in the graveyard scene, where the statue of Il Commendatore nods one final time, to Don Giovanni and not to Leporello (something that is pointedly not in the libretto), making Schrott’s Don squeal and take to his heels. It seems unlikely that Don Giovanni would ever lower himself to appearing scared of his own damnation, even if he were actually scared.

Erwin Schrott as Don Giovanni, Washington National Opera, 2007, photo by Karin Cooper